Midwifery is the health science and health profession that deals with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, in addition to the sexual and reproductive health of women throughout their lives. In many countries, midwifery is a medical profession. A professional in midwifery is known as a midwife.

The pater familias, also written as paterfamilias, was the head of a Roman family. The pater familias was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his extended family. The term is Latin for "father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate". The form is archaic in Latin, preserving the old genitive ending in -ās, whereas in classical Latin the normal first declension genitive singular ending was -ae. The pater familias always had to be a Roman citizen.

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, if she is unable to nurse the child herself sufficiently or chooses not to do so. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some societies, the families are linked by a special relationship of milk kinship. Wet-nursing existed in societies around the world until the invention of reliable formula milk in the 20th century. The practice has made a small comeback in the 21st century.

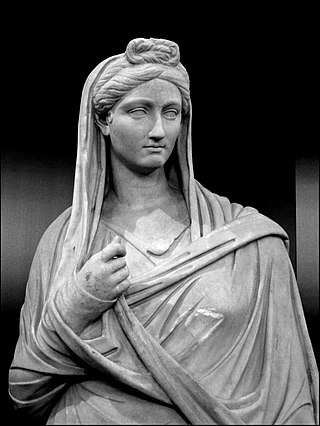

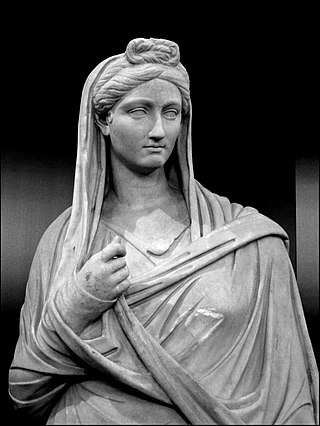

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to childhood:

A bulla, an amulet worn like a locket, was given to male children in Ancient Rome nine days after birth. Rather similar objects are rare finds from Late Bronze Age Ireland.

In ancient Roman religion, the Liberalia was the festival of Liber Pater and his consort Libera. The Romans celebrated Liberalia with sacrifices, processions, ribald and gauche songs, and masks which were hung on trees.

Social class in ancient Rome was hierarchical, with multiple and overlapping social hierarchies. An individual's relative position in one might be higher or lower than in another, which complicated the social composition of Rome.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

Education in ancient Rome progressed from an informal, familial system of education in the early Republic to a tuition-based system during the late Republic and the Empire. The Roman education system was based on the Greek system – and many of the private tutors in the Roman system were enslaved Greeks or freedmen. The educational methodology and curriculum used in Rome was copied in its provinces and provided a basis for education systems throughout later Western civilization. Organized education remained relatively rare, and there are few primary sources or accounts of the Roman educational process until the 2nd century AD. Due to the extensive power wielded by the pater familias over Roman families, the level and quality of education provided to Roman children varied drastically from family to family; nevertheless, Roman popular morality came eventually to expect fathers to have their children educated to some extent, and a complete advanced education was expected of any Roman who wished to enter politics.

Childbirth and obstetrics in classical antiquity were studied by the physicians of ancient Greece and Rome. Their ideas and practices during this time endured in Western medicine for centuries and many themes are seen in modern women's health. Classical gynecology and obstetrics were originally studied and taught mainly by midwives in the ancient world, but eventually scholarly physicians of both sexes became involved as well. Obstetrics is traditionally defined as the surgical specialty dealing with the care of a woman and her offspring during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (recovery). Gynecology involves the medical practices dealing with the health of women's reproductive organs and breasts.

The Inuit are indigenous people who live in the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America. The ancestors of the present-day Inuit are culturally related to Iñupiat and Yupik, and the Aleut, who live in the Aleutian Islands of Siberia and Alaska. The word "Eskimo" has been used to encompass the Inuit and Yupik, and other indigenous Alaskan and Siberian peoples, but this usage is in decline.

Childbirth in rural Appalachia has long been a subject of concern amongst the population because infant mortality rates are higher in Appalachia than in other parts of the United States. Additionally, poor health in utero, at birth, and in childhood can contribute to poor health throughout life. The region's low income, geographic isolation, and low levels of educational attainment reduce both access to and utilization of modern medical care. Traditional medical practices, including lay midwifery, persisted longer in Appalachia than in other U.S. regions.

The ancient Roman family was a complex social structure, based mainly on the nuclear family, but also included various combinations of other members, such as extended family members, household slaves, and freed slaves. Ancient Romans had different names to describe their concepts of family, such as, "familia" to describe the nuclear family and "domus" which would have included all the inhabitants of the household. The types of interactions between the different members of the family were dictated by the perceived social roles each member played. An ancient Roman family's structure was constantly changing as a result of the low life expectancy and through marriage, divorce, and adoption.

In ancient Rome the dies lustricus was a traditional naming ceremony in which an infant was purified and given a praenomen. This occurred on the eighth day for girls and the ninth day for boys, a difference Plutarch explains by noting that "it is a fact that the female grows up, and attains maturity and perfection before the male." Until the umbilical cord fell off, typically on the seventh day, the baby was regarded as "more like a plant than an animal," as Plutarch expresses it. The ceremony of the dies lustricus was thus postponed until the last tangible connection to the mother's body was dissolved and the child was seen "as no longer forming part of the mother, and in this way as possessing an independent existence which justified its receiving a name of its own and therefore a fate of its own." The day was celebrated with a family feast. The childhood goddess Nundina presided over the event, and the goddess Nona was supposed to determine a person's lifespan. Prior to the ceremony infants were not considered part of the household, even if their father had raised them up during a tollere liberum.

The tollere liberum was an ancient Roman tradition in which a man picked up a newly born infant from the ground and lifted them in the air to display his acceptance of them as part of his household. It was commonly the father, or in some cases the chief of the house, who performed the task. In some variations of the tradition the man would carry them around a portion of earth.

In ancient Rome, contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free person who was usually a former slave or the child of a former slave. A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis, the basic and general meaning of which was "companion".

Modern historians' knowledge of ancient Roman gynecology and obstetrics primarily comes from Soranus of Ephesus' four-volume treatise on gynecology. His writings covered medical conditions such as uterine prolapse and cancer and treatments involving materials such as herbs and tools such as pessaries. Ancient Roman doctors believed that menstruation was designed to rid the female body of excess fluids. They believed that menstrual blood had special powers. Roman doctors may also have noticed conditions such as premenstrual syndrome.

Swaddled babyvotives are figures of babies offered as an entreaty to a god or goddess, for healthy pregnancy and childbirth. They have been recovered from ancient Italian Roman temple sanctuary sites.