Scandinavia is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. Scandinavia most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In English usage, it can sometimes also refer more narrowly to the Scandinavian Peninsula, or more broadly to all of the Nordic countries, also including Finland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands.

The Viking Age (793–1066 CE) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germanic Iron Age. The Viking Age applies not only to their homeland of Scandinavia but also to any place significantly settled by Scandinavians during the period. The Scandinavians of the Viking Age are often referred to as Vikings as well as Norsemen, although few of them were Vikings in sense of being engaged in piracy.

Vikings is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia, who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and settled throughout parts of Europe. They also voyaged as far as the Mediterranean, North Africa, Volga Bulgaria, the Middle East, and North America. In their countries of origin, and some of the countries they raided and settled in, this period is popularly known as the Viking Age, and the term "Viking" also commonly includes the inhabitants of the Scandinavian homelands as a collective whole. The Vikings had a profound impact on the early medieval history of Scandinavia, the British Isles, France, Estonia, and Kievan Rus'.

Sweyn Forkbeard was King of Denmark from 986 until his death, King of England for five weeks from December 1013 until his death, and King of Norway from 999/1000 until 1013/14. He was the father of King Harald II of Denmark, King Cnut the Great, and Queen Estrid Svendsdatter.

Harald Fairhair was a Norwegian king. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he reigned from c. 872 to 930 and was the first King of Norway. Supposedly, two of his sons, Eric Bloodaxe and Haakon the Good, succeeded Harald to become kings after his death.

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relative. In most contexts, it means the inheritance of the firstborn son ; it can also mean by the firstborn daughter.

In English common law, fee tail or entail is a form of trust, established by deed or settlement, that restricts the sale or inheritance of an estate in real property and prevents that property from being sold, devised by will, or otherwise alienated by the tenant-in-possession, and instead causes it to pass automatically, by operation of law, to an heir determined by the settlement deed. The term fee tail is from Medieval Latin feodum talliatum, which means "cut(-short) fee". Fee tail deeds are in contrast to "fee simple" deeds, possessors of which have an unrestricted title to the property, and are empowered to bequeath or dispose of it as they wish. Equivalent legal concepts exist or formerly existed in many other European countries and elsewhere.

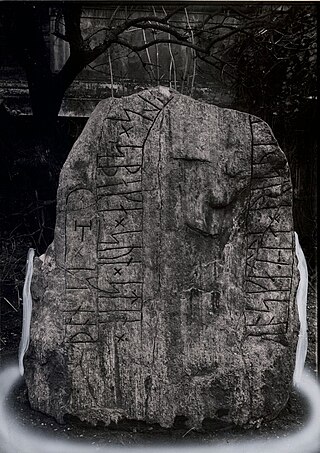

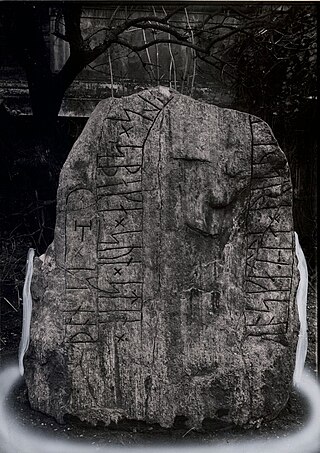

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones date from the late Viking Age. Most runestones are located in Scandinavia, but there are also scattered runestones in locations that were visited by Norsemen during the Viking Age. Runestones are often memorials to dead men. Runestones were usually brightly coloured when erected, though this is no longer evident as the colour has worn off. The vast majority of runestones are found in Sweden.

A thrall was a slave or serf in Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The corresponding term in Old English was þēow. The status of slave contrasts with that of the freeman and the nobleman. The Middle Latin rendition of the term in early Germanic law is servus.

Knowledge about military technology of the Viking Age is based on relatively sparse archaeological finds, pictorial representation, and to some extent on the accounts in the Norse sagas and laws recorded in the 14th century.

The Odelsrett is an ancient Scandinavian allodial title which has survived in Norway as odelsrett and existed until recent times in Sweden as bördsrätt.

Norse funerals, or the burial customs of Viking Age North Germanic Norsemen, are known both from archaeology and from historical accounts such as the Icelandic sagas and Old Norse poetry.

A bastard in the law of England and Wales is an illegitimate child, that is, one whose parents were not married at the time of his or her birth. Unlike in many other systems of law, there was previously no possibility of post factum legitimisation of a bastard. This situation was changed in 1926.

Medieval Scandinavian law, also called North Germanic law, was a subset of Germanic law practiced by North Germanic peoples. It was originally memorized by lawspeakers, but after the end of the Viking Age they were committed to writing, mostly by Christian monks after the Christianization of Scandinavia. Initially, they were geographically limited to minor jurisdictions (lögsögur), and the Bjarkey laws concerned various merchant towns, but later there were laws that applied to entire Scandinavian kingdoms. Each jurisdiction was governed by an assembly of free men, called a þing.

Viking expansion was the historical movement which led Norse explorers, traders and warriors, the latter known in modern scholarship as Vikings, to sail most of the North Atlantic, reaching south as far as North Africa and east as far as Russia, and through the Mediterranean as far as Constantinople and the Middle East, acting as looters, traders, colonists and mercenaries. To the west, Vikings under Leif Erikson, the heir to Erik the Red, reached North America and set up a short-lived settlement in present-day L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada. Longer lasting and more established Norse settlements were formed in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Russia, Ukraine, Great Britain, Ireland and Normandy.

Norse religious worship is the traditional religious rituals practiced by Norse pagans in Scandinavia in pre-Christian times. Norse religion was a folk religion, and its main purpose was the survival and regeneration of society. Therefore, the faith was decentralized and tied to the village and the family, although evidence exists of great national religious festivals. The leaders managed the faith on behalf of society; on a local level, the leader would have been the head of the family, and nationwide, the leader was the king. Pre-Christian Scandinavians had no word for religion in a modern sense. The closest counterpart is the word sidr, meaning custom. This meant that Christianity, during the conversion period, was referred to as nýr sidr while paganism was called forn sidr. The center of gravity of pre-Christian religion lay in religious practice – sacred acts, rituals and worship of the gods.

Frögärd Ulvsdotter i Ösby was a Swedish Norse woman. She was according to a common misconception believed to be a Viking Age female runemaster. This notion is based on Erik Brate's erroneous interpretation of runestone U 203. As early as 1943, Elias Wessén convincingly demonstrated that the sequence in question cannot be read as a carver's signature. Also, the place name uisby should be read Väsby rather than Ösby.

Peter Hayes Sawyer was a British historian. His work on the Vikings was highly influential, as was his scholarship on Medieval England. Sawyer's early work The Age of the Vikings argued that the Vikings were "traders not raiders", overturning the previously held view that the Vikings' voyages were only focused on destruction and pillaging.

The term "Viking Age" refers to the period roughly from 790s to the late 11th century in Europe, though the Norse raided Scotland's western isles well into the 12th century. In this era, Viking activity started with raids on Christian lands in England and eventually expanded to mainland Europe, including parts of present-day Russia. While maritime battles were very rare, Viking bands proved very successful in raiding coastal towns and monasteries due to their efficient warships, and intimidating war tactics, skillful hand-to-hand combat, and fearlessness. What started as Viking raids on small towns transformed into the establishment of important agricultural spaces and commercial trading-hubs across Europe through rudimentary colonization. Vikings' tactics in warfare gave them an enormous advantage in successfully raiding, despite their small population in comparison to that of their enemies.

Runestone DR 120, MJy 51, known as Spentrup stone 2 and the Jennum stone, is a Viking Age runestone engraved with the Younger Futhark and a Thor's hammer.