The Battle of Guadalete was the first major battle of the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, fought in 711 at an unidentified location in what is now southern Spain between the Visigoths under their king, Roderic, and the invading forces of the Umayyad Caliphate, composed mainly of Berbers and some Arabs under the commander Tariq ibn Ziyad. The battle was significant as the culmination of a series of Berber attacks and the beginning of al-Andalus. Roderic was killed in the battle, along with many members of the Visigothic nobility, opening the way for the capture of the Visigothic capital of Toledo.

The Mozarabs, or more precisely Andalusi Christians, were the Christians of al-Andalus, or the territories of Iberia under Muslim rule from 711 to 1492. Following the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania, the Christian population of much of Iberia came under Muslim control.

The Kingdom of León was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in 910 when the Christian princes of Asturias along the northern coast of the peninsula shifted their capital from Oviedo to the city of León. The kings of León fought civil wars, wars against neighbouring kingdoms, and campaigns to repel invasions by both the Moors and the Vikings, all in order to protect their kingdom's changing fortunes.

Andalusi Romance, also called Mozarabic or Ajami, is the varieties of Ibero-Romance that developed in Al-Andalus, the parts of the medieval Iberian Peninsula under Islamic control. Romance, or vernacular Late Latin, was the common tongue for the great majority of the Iberian population at the time of the Umayyad conquest in the early eighth century, but over the following centuries, it was gradually superseded by Andalusi Arabic as the main spoken language in the Muslim-controlled south. At the same time, as the northern Christian kingdoms pushed south into Al-Andalus, their respective Romance varieties gained ground at the expense of Andalusi Romance as well as Arabic. The final extinction of the former may be estimated to 1300 CE.

The Mozarabic Rite, officially called the Hispanic Rite, and in the past also called the Visigothic Rite, is a liturgical rite of the Latin Church once used generally in the Iberian Peninsula (Hispania), in what is now Spain and Portugal. While the liturgy is often called 'Mozarabic' after the Christian communities that lived under Muslim rulers in Al-Andalus that preserved its use, the rite itself developed before and during the Visigothic period. After experiencing a period of decline during the Reconquista, when it was superseded by the Roman Rite in the Christian states of Iberia as part of a wider programme of liturgical standardization within the Catholic Church, efforts were taken in the 16th century to revive the rite and ensure its continued presence in the city of Toledo, where it is still celebrated today. It is also celebrated on a more widespread basis throughout Spain and, by special dispensation, in other countries, though only on special occasions.

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, also known as the Arab conquest of Spain, by the Umayyad Caliphate occurred between approximately 711 and the 720s. The conquest resulted in the destruction of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom of Spain and led to the establishment of a Muslim Arabian-Moorish state, Al-Andalus.

Egilona was a Visigothic noblewoman and the last known queen of the Visigoths. She was the wife first of Roderic, the Visigothic king (710–11), and then of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, Muslim governor (wālī) of al-Andalus (714–16). Her name is rendered Aylū by Arabic writers, who also give her the kunyaUmm ʿAṣim. She was independently wealthy.

Muladí were the native population of the Iberian Peninsula who adopted Islam after the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century. The demarcation of muladíes from the population of Arab and Berber extraction was relevant in the first centuries of Islamic rule, however, by the 10th century, they diluted into the bulk of the society of al-Andalus. In Sicily, Muslims of local descent or of mixed Arab, and Sicilian origin were also sometimes referred to as Muwallad. They were also called Musalimah ('Islamized'). In broader usage, the word muwallad is used to describe Arabs of mixed parentage, especially those not living in their ancestral homelands.

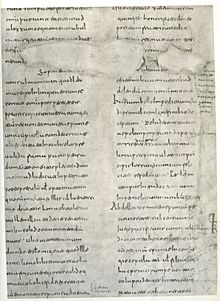

Mozarabic chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Visigothic/Mozarabic rite of the Catholic Church, related to the Gregorian chant. It is primarily associated with Hispania under Visigothic rule and later with the Mozarabs and was replaced by the chant of the Roman rite following the Christian Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Although its original medieval form is largely lost, a few chants have survived with readable musical notation, and the chanted rite was later revived in altered form and continues to be used in a few isolated locations in Spain, primarily in Toledo.

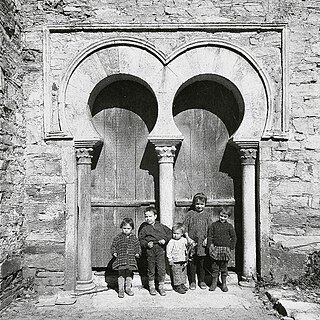

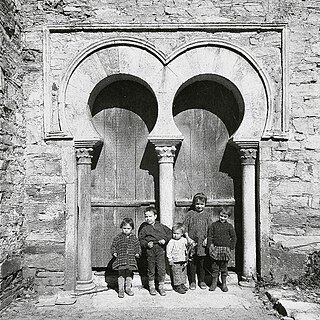

The designation artede (la) repoblación was first proposed by José Camón Aznar in 1949 to replace the term Mozarabic as applied to certain works of architecture from the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain between the end of the 9th and beginning of the 11th centuries. Camón argued that these buildings were related stylistically to the architecture of Asturias and owed little to Andalusian styles. Moreover, since they were built by Christians living under Christian rule, neither were they Mozarabic.

Mozarabic art is an early medieval artistic style that is part of the pre-Romanesque style and is linked to the kingdom of León. It was developed by the Hispanic Christians who lived in Muslim territory and in the expansion territories of the León crown, in the period from the Muslim invasion (711) to the end of the 11th century. During this period, disciplines such as painting, goldsmithing and architecture with marked Caliphate influences were cultivated in a context of medieval coexistence - Christian, Hebrew and Muslim - in which the territories were constantly changing in size and status. Other names for this artistic style are Leonese art or repopulation art.

The Archdiocese of Mérida–Badajoz is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory of the Catholic Church in Spain, created in 1255. Until 1994, it was known as the Diocese of Badajoz.

The Diocese of Beja is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic church in Portugal. It is a suffragan of the archdiocese of Évora.

The Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist is a Catholic cathedral in Badajoz, Extremadura, western Spain. Since 1994, together with the Co-cathedral of Saint Mary Major of Mérida, it is the seat of the Archdiocese of Mérida-Badajoz.

The Chronicle of 741 is a Latin-language history in 43 sections or paragraphs, many of which are quite short, which was composed in about the years 741-743 in al-Andalus. It is the earliest known Christian work produced under Muslim rule in Iberia.

The toponym al-Andalus (الأندلس) is first attested in inscriptions on coins minted by the Umayyad rulers of Iberia, from ca. 715.

Hafs ibn Albar al-Qūṭī, commonly known as al-Qūṭī or al-Qurṭubî, was a 9th–10th Century Visigothic Christian count, theologian, translator and poet, often memorialised as the 'Last of the Goths'. He was a descendant of Visigothic royalty and held a position of power over the Christians of his region. He was possibly a priest or censor, but many scholars take him to be a layman. He describes himself as ignorant of the sacred sciences, and constantly allowed his works to be checked and commented on by those he called "best in their religion and a bright light in the sacred sciences", claiming that "all of them know what I do not know".

The literature of al-Andalus, also known as Andalusi literature, was produced in al-Andalus, or Islamic Iberia, from the Muslim conquest in 711 to either the Catholic conquest of Granada in 1492 or the expulsion of the Moors ending in 1614. Andalusi literature was written primarily in Arabic, but also in Hebrew, Latin, and Romance.

The Crusade of Alfonso I of Aragon in Andalusia was a campaign carried out for nine months by Alfonso I the Battler in the interior of al-Andalus, where he camped for a long time near Granada, he plundered fields and riches, he defeated the Almoravid army in pitched battle in Arnisol Anzur, near Puente Genil, south of the current province of Córdoba) and rescued a contingent of Mozarabs with which he repopulated the lands of the Ebro Valley recently conquered by the kingdom of Aragon. The initial objective was to establish a Christian principality in Granada, relying on the Mozarabic population that had insistently requested help from the king of Aragon, as it was subject to the religious fanaticism of the Almoravid period. The Mozarabs of Granada proposed to Alfonso the Battler an internal rebellion against the ruling authority with the support of the Aragonese host; The conjunction was necessary, since Alfonso I, unlike the strategy used in the conquest of Zaragoza in 1118, did not bring assault machinery to Granada, a transport that was in any case extremely impracticable given the long distance that the expedition would travel and the logistical difficulties involved in penetrating so deeply into enemy territory.

Mozarabic literature is the literature of the Mozarabs, Christians living under Islamic rule in Spain and their Arabized descendants. They produced literature in both Latin and Arabic.