Related Research Articles

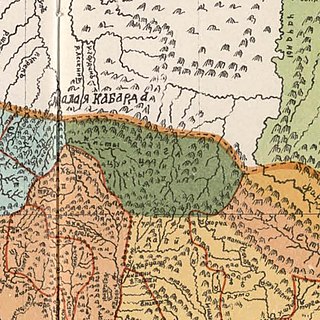

Circassia, also known as Zichia, was a country and a historical region in Eastern Europe. It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Circassian War (1763–1864), after which approximately 99.5–99.8% of the Circassian people were either exiled or massacred in the Circassian genocide.

Kumyks are a Turkic ethnic group living in Dagestan, Chechnya and North Ossetia. They are the largest Turkic people in the North Caucasus.

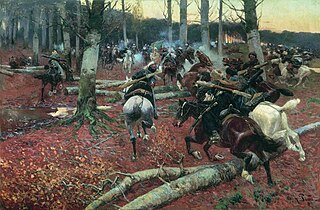

The Caucasian War or the Caucasus War was a 19th-century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. It consisted of a series of military actions waged by the Russian Imperial Army and Cossack settlers against the native inhabitants such as the Adyghe, Abaza-Abkhazians, Ubykhs, Chechens, and Dagestanis as the Tsars sought to expand.

Shamkhal, or Shawhal is a title used by Kumyk rulers in Dagestan and the Northeast Caucasus during the 8th–19th centuries. By the 16th century, the state had its capital at Tarki and was thus known as the Shamkhalate of Tarki.

The Sadz or Asadzwa, also Jigets, are a subethnic group of the Abkhazians. They are sometimes purported to have originated from the Sanigoi tribe mentioned by the Classic authors. In the 6th century, they formed a tribal principality, which later commingled with the Abasgoi, Apsilae and Missimianoi into the Kingdom of Abkhazia.

"Gazikumukh Shamkhalate" is a term introduced in Russian-Dagestan historiography starting from the 1950s–60s to denote the Kumyk state that existed on the territory of present-day Dagestan in the period of the 8th to 17th centuries with the capital in Gazi-Kumukh, and allegedly disintegrated in 1642. However, In the 16th century's Russian archival sources Tarki is stated to be the "capital of Shamkhalate" and "the city of Shamkhal", while "Kazi-Kumuk" is mentioned as a residence. These facts contradict "1642 disintegration" date. Moreover, there is absolutely no source before the 1950s containing the term "Gazikumukh Shamkhalate" or a statement that Gazi-Kumukh had ever been the capital of Shamkhalate. Historically, Shamkhalate is widely described as Tarki Shamkhalate or just Shamkhalate.

The Shamkhalate of Tarki, or Tarki Shamkhalate was a Kumyk state in the eastern part of the North Caucasus, with its capital in the ancient town of Tarki. It formed on the territory populated by Kumyks and included territories corresponding to modern Dagestan and adjacent regions. After subjugation by the Russian Empire, the Shamkhalate's lands were split between the Empire's feudal domain with the same name extending from the river Sulak to the southern borders of Dagestan, between Kumyk possessions of the Russian Empire and other administrative units.

The Durdzuks, also known as Dzurdzuks, was a medieval exonym of the 9th-18th centuries used mainly in Georgian, Arabic, but also Armenian sources in reference to the Vainakh peoples.

The House of Lopukhin was an old Russian noble family, most influential during the Russian Empire, forming one of the branches of the Sorokoumov-Glebov family.

Kumykia, or rarely called Kumykistan, is a historical and geographical region located along the Caspian Sea shores, on the Kumyk plateau, in the foothills of Dagestan and along the river Terek. The term Kumykia encompasses territories which are historically and currently populated by the Turkic-speaking Kumyk people. Kumykia was the main "granary of Dagestan". The important trade routes, such as one of the branches of the Great Silk Road, passed via Kumykia.

The Kanzhal War or Crimean-Circassian War of 1708 was military conflict in 1708 fought between 7,000 Circassians led by Kurgoqo Atajuq and 30,000–100,000 Crimean Tatars led by Qaplan I Giray, which resulted in Circassian victory. It played a big role in decreasing foreign influence in Circassia. In 2013, the Russian Academy of Sciences described the battle as "an important event in the history of Circassians". It was fought near the village of Bylym on the Baksan River.

The Khegayk or Shegayk were one of the Circassian tribes. They were completely exterminated in the Circassian genocide following the Russo-Circassian War. None were recorded to have survived. In some sources, they are also mentioned under the name "Shegayk".

Gligvi is a medieval ethnonym used in Georgian, Russian and Western European sources in the 11-19 centuries. The ethnonym corresponds to the self-name of the Ingush, Ghalghaï.

Fappi or Fappi mokhk, exonym: Kistetia, is a historical region in Ingushetia. Fappi is the territory of historical settlement of the Fyappiy society.

Galashians, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society, which formed in the middle of the 18th century. The name comes from the village of Galashki, which is geographically located in the very center of the society. Galashians were located in the middle and lower reaches of the river Assa and the basin of the river Fortanga.

Ingush societies or shahars were ethnoterritorial associations of the Ingush based on the geographical association of several villages and intended for conditional administrative-territorial delimitation of the Ingush ethnic group. The formation and functioning of most of them dates back to the late Middle Ages. During this period, their boundaries, number and names changed.

The Nazranians were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial subethnic group (society) which inhabited modern day Nazranovsky District and Prigorodny District.

The Dzherakh, also spelled Jerakh, historically also known as Erokhan people, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society, today a tribal organization/clan (teip), that was formed in the Dzheyrakhin gorge, as well as in the area of the lower reaches of the Armkhi River and the upper reaches of the Terek River.

Khamkhins, also known as Ghalghaï, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society, which was located in the upper reaches of the Assa River. The Khamkhin society, like the Tsorin society, was formed from the former "Ghalghaï society" as a result of the transfer of rural government to Khamkhi.

Tsorins, Tsori, also Ghalghaï, were a historical Ingush ethnoterritorial society that was located in mountainous Ingushetia in the region of river Guloykhi. The center of the society was Tsori from which it got its name. Tsorin society, like the Khamkhin society, was formed from the former "Galgai society" as a result of the transfer (appearance) of rural government to the village Tsori.

References

- 1 2 Эпиграфические памятники Северного Кавказа. — М.: Наука, 1966. Ч. I. — С. 202

- ↑ М.Г. Волкова «Этнонимы и племенные названия Северного Кавказа». 1974: стр. 21, 23

- ↑ «Полное собрание русских летописей, изданное по Высочайшему повелению Археографическою Комиссиею», 1841-2004-.-, v. VII., p. 56.

- ↑ Фурсов А. И. Курс лекций по русской истории: Лек. 6. Русь в 12-13 вв. (9:50 — 11:30).

- ↑ Сборник материалов, относящихся к истории Золотой Орды. т. II. — М.-Л.: Изд-во АН СССР, 1941. — С. 37.

- ↑ «Полное собрание русских летописей, изданное по Высочайшему повелению Археографическою Комиссиею», 1841-2004-.-, v. XI., p. 7.

- ↑ «Полное собрание русских летописей, изданное по Высочайшему повелению Археографическою Комиссиею», 1841-2004-.-, v. VI, issue 1, p. 455

- ↑ «Полное собрание русских летописей, изданное по Высочайшему повелению Археографическою Комиссиею», V. XI., p. 46, 47

- ↑ «История Российская с самых древнейших времён, неусыпными трудами через тридцать лет собранная и описанная покойным тайным советником и астраханским губернатором Васильем Никитичем Татищевым» — цит. по Татищев В. Н. История Российская. В 3 т. — М.: АСТ, «Ермак», 2005. — (Классическая мысль).

- ↑ Карамзин Н. М. История государства Российского: в 12 томах. — СПб.: Тип. Н. Греча, 1816—1829. v. V — part IV

- 1 2 Карамзин Н. М. История государства Российского: в 12 томах. — СПб.: Тип. Н. Греча, 1816—1829. v. VIII — part IV

- ↑ Лопатин А. Москва — М., 1948. — С. 57.

- ↑ Алексей Михайлович, Андреев Игорь Львович, 178 страниц, Молодая гвардия, Москва, 2003, ISBN 5-235-02552-0

- 1 2 Îzahlı Osmanlı Tarihi Kronolojisi, İsmail Hami Danişmend, Türkiye Yayınevi, 1961

- ↑ Кабардино-русские отношения в XVI-XVIII вв. Том 1. М. АН СССР. 1957 стр. 223

- ↑ Русско-дагестанские отношения в XVIII–начале XIX веков (Сборник документов под ред. В. Г. Гаджиева). (В дальнейшем РДО). М. 1988. стр. 189; Магомедов Р. М.

- ↑ Эпиграфические памятники Северного Кавказа. — М.: Наука, 1966. Ч. I. — С. 203

- ↑ История, география и этнография Дагестана XVIII—XIX вв. Архивные материалы / под ред. М. О. Косвена и Х.-М. О. Хашаева. — М., 1958. — С. 94)

- ↑ "Документы Крым Джиованни Де Лукка (жан Де Люк), Описание Перекопских И Ногайских Татар (1633?). Адыги, балкарцы и карачаевцы в известиях европейских авторов XIII-XIX вв. Нальчик. Эльбрус. 1974". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "Адам Олеарий, Описание Путешествия В Московию И Персию, Публикация 1906 Г., Части 77-81".

- ↑ "«Новейшие государства Казань, Астрахань, Грузия и многие другие, царю, султану и шаху платившие дань и подвластные...». Нюрнберг, 1723 — перевод с немецкого Е. С. Зевакина". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ↑ "Де Бларамберг «Историческое, топографическое, статистическое, этнографическое и военное описание Кавказа», ч. 1-3. 1836 (Центральный государственный архив. ВУА, дело № 18508) — перевод с французского А. И. Петрова". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- 1 2 "Теофил Лапинский. Горцы Кавказа и их освободительная борьба против русских. Описание очевидца Теофила Лапинского (Теффик-бея) полковника и командира польского отряда в стране независимых горцев. Нальчик. Эль-Фа. 1995". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ Адыгский фактор в этнополитическом развитии Северного Кавказа, Олег Бубенок, 2015, Журнал Центральная Азия и Кавказ, Central Asia & Central Caucasus Press AB, ISSN Печатный: 1403-7068, Электронный: 2002-3847

- ↑ Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 by James Stanislaus Bell (Vol. I & II), 1840, London : Edward Moxon, Language: English, 2 Volumes, v2, Letter 19, page 53