| Part of a series on |

| Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions |

|---|

|

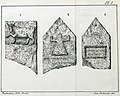

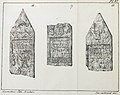

The Cirta steles are almost 1,000 Punic funerary[ citation needed ] and votive steles found in Cirta (today Constantine, Algeria) in a cemetery located on a hill immediately south of the Salah Bey Viaduct.

Contents

- Judas steles

- Costa steles

- Overview

- Concordance

- Gallery

- Berthier steles

- Overview 2

- Bibliography

- References

- External sources

The first group of steles were published by Auguste Celestin Judas in 1861. The Lazare Costa inscriptions were the second group of these inscriptions found; they were discovered between 1875 and 1880 by Lazare Costa, a Constantine-based Italian antiquarian. Most of the steles are now in the Louvre. [2] [3] [4] These are known as KAI 102–105.

In 1950, hundreds of additional steles were excavated from the same location – then named El Hofra – by André Berthier, director of the Gustave-Mercier Museum (today the Musée national Cirta) and Father René Charlier, professor at the Constantine seminary. [5] Many of these steles are now in the Musée national Cirta. [6] Over a dozen of the most notable inscriptions were later published in Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften and are known as 106-116 (Punic) and 162-164 (Neo Punic).