A state is a political entity that regulates society and the population within a territory. Government is considered to form the fundamental apparatus of contemporary states.

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organized groups. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular or irregular military forces. Warfare refers to the common activities and characteristics of types of war, or of wars in general. Total war is warfare that is not restricted to purely legitimate military targets, and can result in massive civilian or other non-combatant suffering and casualties.

Environmental determinism is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular economic or social developmental trajectories. Jared Diamond, Jeffrey Herbst, Ian Morris, and other social scientists sparked a revival of the theory during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This "neo-environmental determinism" school of thought examines how geographic and ecological forces influence state-building, economic development, and institutions. While archaic versions of the geographic interpretation were used to encourage colonialism and eurocentrism, modern figures like Diamond use this approach to reject the racism in these explanations. Diamond argues that European powers were able to colonize, due to unique advantages bestowed by their environment, as opposed to any kind of inherent superiority.

A failed state is a state that has lost its ability to fulfill fundamental security and development functions, lacking effective control over its territory and borders. Common characteristics of a failed state include a government incapable of tax collection, law enforcement, security assurance, territorial control, political or civil office staffing, and infrastructure maintenance. When this happens, widespread corruption and criminality, the intervention of state and non-state actors, the appearance of refugees and the involuntary movement of populations, sharp economic decline, and military intervention from both within and outside the state are much more likely to occur.

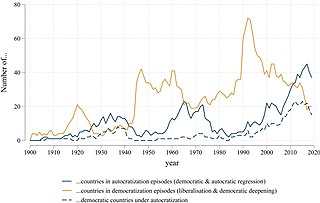

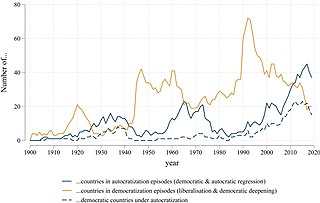

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

In political philosophy, a monopoly on violence or monopoly on the legal use of force is the property of a polity that is the only entity in its jurisdiction to legitimately use force, and thus the supreme authority of that area.

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word mobilization was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and tactics have continuously changed since then. The opposite of mobilization is demobilization.

Rebellion is a violent uprising against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a portion of a state. A rebellion is often caused by political, religious, or social grievances that originate from a perceived inequality or marginalization.

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats of using force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy during the Cold War with regard to the use of nuclear weapons and is related to but distinct from the concept of mutual assured destruction, according to which a full-scale nuclear attack on a power with second-strike capability would devastate both parties. The central problem of deterrence revolves around how to credibly threaten military action or nuclear punishment on the adversary despite its costs to the deterrer. Deterrence in an international relations context is the application of deterrence theory to avoid conflict.

The Military Revolution is the theory that a series of radical changes in military strategy and tactics during the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in major lasting changes in governments and society. The theory was introduced by Michael Roberts in the 1950s as he focused on Sweden (1560–1660) searching for major changes in the European way of war caused by the introduction of portable firearms. Roberts linked military technology with larger historical consequences, arguing that innovations in tactics, drill and doctrine by the Dutch and Swedes (1560–1660), which maximized the utility of firearms, led to a need for more trained troops and thus for permanent forces. Armies grew much larger and more expensive. These changes in turn had major political consequences in the level of administrative support and the supply of money, men and provisions, producing new financial demands and the creation of new governmental institutions. "Thus, argued Roberts, the modern art of war made possible—and necessary—the creation of the modern state".

Tax revenue is the income that is collected by governments through taxation. Taxation is the primary source of government revenue. Revenue may be extracted from sources such as individuals, public enterprises, trade, royalties on natural resources and/or foreign aid. An inefficient collection of taxes is greater in countries characterized by poverty, a large agricultural sector and large amounts of foreign aid.

Charles Tilly was an American sociologist, political scientist, and historian who wrote on the relationship between politics and society. He was a professor of history, sociology, and social science at the University of Michigan from 1969 to 1984 before becoming the Joseph L. Buttenwieser Professor of Social Science at Columbia University.

State-building as a specific term in social sciences and humanities, refers to political and historical processes of creation, institutional consolidation, stabilization and sustainable development of states, from the earliest emergence of statehood up to the modern times. Within historical and political sciences, there are several theoretical approaches to complex questions related to the role of various contributing factors in state-building processes.

Sidney George Tarrow is an emeritus professor of political science, known for his research in the areas of comparative politics, social movements, political parties, collective action and political sociology.

The effects of war are widely spread and can be long-term or short-term. Soldiers experience war differently than civilians. Although both suffer in times of war, women and children suffer atrocities in particular. In the past decade, up to two million of those killed in armed conflicts were children. The widespread trauma caused by these atrocities and suffering of the civilian population is another legacy of these conflicts, the following creates extensive emotional and psychological stress. Present-day internal wars generally take a larger toll on civilians than state wars. This is due to the increasing trend where combatants have made targeting civilians a strategic objective. A state conflict is an armed conflict that occurs with the use of armed force between two parties, of which one is the government of a state. "The three problems posed by state conflict are the willingness of UN members, particularly the strongest member, to intervene; the structural ability of the UN to respond; and whether the traditional principles of peacekeeping should be applied to intra‐state conflict". Effects of war also include mass destruction of cities and have long lasting effects on a country's economy. Armed conflict has important indirect negative consequences on infrastructure, public health provision, and social order.

Networked advocacy or net-centric advocacy refers to a specific type of advocacy. While networked advocacy has existed for centuries, it has become significantly more efficacious in recent years due in large part to the widespread availability of the internet, mobile telephones, and related communications technologies that enable users to overcome the transaction costs of collective action.

State formation is the process of the development of a centralized government structure in a situation in which one did not exist. State formation has been a study of many disciplines of the social sciences for a number of years, so much so that Jonathan Haas writes, "One of the favorite pastimes of social scientists over the course of the past century has been to theorize about the evolution of the world's great civilizations."

Fiscal capacity is the ability of the state to extract revenues to provide public goods and carry out other functions of the state, given an administrative, fiscal accounting structure. In economics and political science, fiscal capacity may be referred to as tax capacity, extractive capacity or the power to tax, as taxes are a main source of public revenues. Nonetheless, though tax revenue is essential to fiscal capacity, taxes may not be the government's only source of revenue. Other sources of revenue include foreign aid and natural resources.

States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control is a book on African state-building by Jeffrey Herbst, former Professor of Politics and International Affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. The book was a co-winner of the 2001 Gregory Luebbert Book Award from the American Political Science Association in comparative politics. It was also a finalist for the 2001 Herskovits Prize awarded by the African Studies Association.

The term territorial state is used to refer to a state, typical of the High Middle Ages, since around 1000 AD, and "other large-scale complex organizations that attained size, stability, capacity, efficiency, and territorial reach not seen since antiquity." The term territorial state is also understood as “coercion-wielding organizations that are distinct from households and kinship groups and exercise clear priority in some respects over all other organizations within substantial territories.” Organizations such as city-states, empires, and theocracies along with many a number of other governmental organizations are considered territorial states, yet does not include tribes, lineages, firms, or churches alike.