Father Damien or Saint Damien of Molokai, SS.CC. or Saint Damien De Veuster, born Jozef De Veuster, was a Roman Catholic priest from Belgium and member of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, a missionary religious institute. He was recognized for his ministry, which he led from 1873 until his death in 1889, in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi to people with leprosy, who lived in government-mandated medical quarantine in a settlement on the Kalaupapa Peninsula of Molokaʻi.

Waimea is a census-designated place (CDP) in Kauaʻi County, Hawaiʻi, United States. The population was 2,057 at the 2020 census. The first Europeans to reach Hawaii landed in Waimea in 1778.

Molokai is the fifth most populated of the eight major islands that make up the Hawaiian Islands archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It is 38 by 10 miles at its greatest length and width with a usable land area of 260 sq mi (673.40 km2), making it the fifth-largest in size of the main Hawaiian Islands and the 27th largest island in the United States. It lies southeast of Oʻahu across the 25 mi (40 km) wide Kaʻiwi Channel and north of Lānaʻi, separated from it by the Kalohi Channel.

The culture of the Native Hawaiians encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms practiced by the original residents of the Hawaiian islands, including their knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits. Humans are estimated to have first inhabited the archipelago between 124 and 1120 AD when it was settled by Polynesians who voyaged to and settled there. Polynesia is made of multiple island groups which extend from Hawaii to New Zealand across the Pacific Ocean. These voyagers developed Hawaiian cuisine, Hawaiian art, and the Native Hawaiian religion.

Marianne Cope, TOSF, also known as Saint Marianne of Molokaʻi, was a German-born American religious sister who was a member of the Sisters of St Francis of Syracuse, New York, and founding leader of its St. Joseph's Hospital in the city, among the first of 50 general hospitals in the country. Known also for her charitable works, in 1883 she relocated with six other sisters to Hawaiʻi to care for persons suffering leprosy on the island of Molokaʻi and aid in developing the medical infrastructure in Hawaiʻi. Despite direct contact with the patients over many years, Cope did not contract the disease.

Kalaupapa is a small unincorporated community and Hawaiian home land on the island of Molokaʻi, within Kalawao County in the U.S. state of Hawaii. In 1866, during the reign of Kamehameha V, the Hawaii legislature passed a law that resulted in the designation of Molokaʻi as the site for a leper colony, where patients who were seriously affected by leprosy could be quarantined, to prevent them from infecting others. At the time, the disease was little understood: it was believed to be highly contagious and was incurable until the advent of antibiotics. The communities where people with leprosy lived were under the administration of the Board of Health, which appointed superintendents on the island.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park located in Kalaupapa, Hawaiʻi, on the island of Molokaʻi. Coterminous with the boundaries of Kalawao County and primarily on Kalaupapa peninsula, it was established by Congress in 1980 to expand upon the earlier National Historic Landmark site of the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement. It is administered by the National Park Service. Its goal is to preserve the cultural and physical settings of the two leper colonies on the island of Molokaʻi, which operated from 1866 to 1969 and had a total of 8500 residents over the decades.

Globalization, the flow of information, goods, capital, and people across political and geographic boundaries, allows infectious diseases to rapidly spread around the world, while also allowing the alleviation of factors such as hunger and poverty, which are key determinants of global health. The spread of diseases across wide geographic scales has increased through history. Early diseases that spread from Asia to Europe were bubonic plague, influenza of various types, and similar infectious diseases.

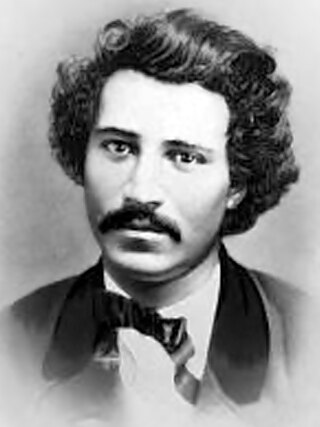

Jonatana Napela or Jonathan Hawaii Napela was one of the earliest Hawaiian converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Hawaii, joining in 1851. He helped translate the Book of Mormon into the Hawaiian language, as "Ka Buke a Moramona," working with missionary George Q. Cannon. Napela was appointed to serve as a superintendent of the colony at Kalaupapa, Molokaʻi, which he did for several years. He had accompanied his wife there after her diagnosis with leprosy. While at the settlement, he led LDS Church members and collaborated with Roman Catholic priest-missionary, Father Damien, to serve all the people of the settlement, most of which were Protestant.

Kalawao is a location on the eastern side of the Kalaupapa Peninsula of the island of Molokai, in Hawaii, which was the site of Hawaii's leper colony between 1866 and the early 20th century. Thousands of people in total came to the island to live in quarantine. It was one of two such settlements on Molokai, the other being Kalaupapa. Administratively Kalawao is part of Kalawao County. The placename means "mountain-side wild woods" in Hawaiian.

The island of Maui with a relatively central location has given it a pivotal role in the history of the Hawaiian Islands.

Molokai: The Story of Father Damien is a 1999 biographical film of Father Damien, a Belgian priest working at the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. It was directed by Paul Cox.

Leprosy stigma is a type of social stigma, a strong negative feeling towards a person with leprosy relating to their moral status in society. It is also referred to as leprosy-related stigma, leprostigma, and stigma of leprosy. Since ancient times, leprosy instilled the practice of fear and avoidance in many societies because of the associated physical disfigurement and lack of understanding behind its cause. Because of the historical trauma the word "leprosy" invokes, the disease is now referred to as Hansen's disease, named after Gerhard Armauer Hansen who discovered Mycobacterium leprae, the bacterial agent that causes Hansen's disease. Those who have suffered from Hansen's disease describe the impact of social stigma as far worse than the physical manifestations despite it being only mildly contagious and pharmacologically curable. This sentiment is echoed by Weis and Ramakrishna, who noted that "the impact of the meaning of the disease may be a greater source of suffering than symptoms of the disease".

The Leper War on Kauaʻi also known as the Koolau Rebellion, Battle of Kalalau or the short name, the Leper War. Following the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, the stricter government enforced the 1865 "Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy" carried out by Attorney General and President of the Board of Health William Owen Smith. A revolt broke out in Kauaʻi, against the forced relocation of all infected by the disease to the Kalaupapa Leprosy Colony of Kalawao on the island of Molokai.

William Keolaloa Kahānui Sumner, Jr. was a high chief of the Kingdom of Hawaii through his mother's family; his father was an English captain from Northampton. Sumner married a Tahitian princess. Aided by royal family connections, he became a major landowner and politician in Hawaii.

There is no definitive date for the Polynesian discovery of Hawaii. However, high-precision radiocarbon dating in Hawaii using chronometric hygiene analysis, and taxonomic identification selection of samples, puts the initial such settlement of the Hawaiian Islands sometime between 1219 and 1266 A.D., originating from earlier settlements first established in the Society Islands around 1025 to 1120 A.D., and in the Marquesas Islands sometime between 1100 and 1200 A.D.

William Phileppus Ragsdale was a Hawaiian lawyer, newspaper editor, and translator. He was a popular figure known for being luna or superintendent of the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement. Elements of his life story influenced Mark Twain's 1889 novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

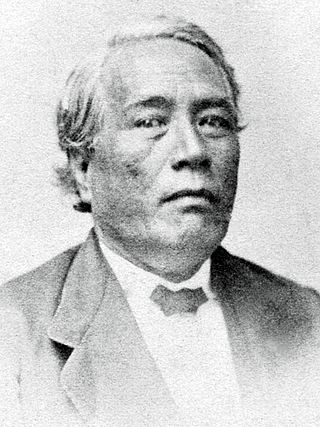

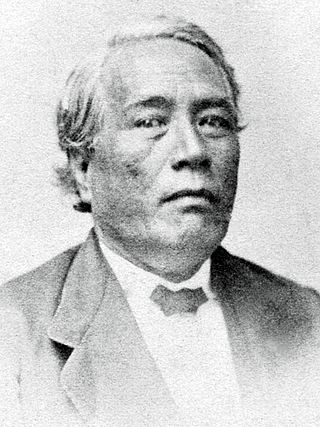

George Naʻea, was a high chief of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and father of Queen Emma of Hawaii. He became one of the first Native Hawaiians to contract leprosy and the disease became known as maʻi aliʻi in the Hawaiian language because of this association.

Ambrose Kanoealiʻi or Ambrose Kanewaliʻi Hutchison was a long-time Native Hawaiian resident of the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement on the island of Molokaʻi who resided there for fifty-three years from 1879 to his death in 1932. During his residence, he assumed a prominent leadership role in the patient community and served as luna or resident superintendent of Kalaupapa from 1884 to 1897.

Arthur Albert St. Maur Mouritz, often credited as A. Mouritz, (1861–1943) was a British physician known for his studies of leprosy in Hawaii. He travelled from England to Hawaii in 1883, and was the resident physician to the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement in Molokai, Hawaii, from 1884 to 1887 or 1888. He found evidence that there were cases of leprosy in Hawaii before 1830.