In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the study of the strong interaction between quarks mediated by gluons. Quarks are fundamental particles that make up composite hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type of quantum field theory called a non-abelian gauge theory, with symmetry group SU(3). The QCD analog of electric charge is a property called color. Gluons are the force carriers of the theory, just as photons are for the electromagnetic force in quantum electrodynamics. The theory is an important part of the Standard Model of particle physics. A large body of experimental evidence for QCD has been gathered over the years.

In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), color confinement, often simply called confinement, is the phenomenon that color-charged particles cannot be isolated, and therefore cannot be directly observed in normal conditions below the Hagedorn temperature of approximately 2 terakelvin. Quarks and gluons must clump together to form hadrons. The two main types of hadron are the mesons and the baryons. In addition, colorless glueballs formed only of gluons are also consistent with confinement, though difficult to identify experimentally. Quarks and gluons cannot be separated from their parent hadron without producing new hadrons.

A quark star is a hypothetical type of compact, exotic star, where extremely high core temperature and pressure have forced nuclear particles to form quark matter, a continuous state of matter consisting of free quarks.

A fermionic condensate is a superfluid phase formed by fermionic particles at low temperatures. It is closely related to the Bose–Einstein condensate, a superfluid phase formed by bosonic atoms under similar conditions. The earliest recognized fermionic condensate described the state of electrons in a superconductor; the physics of other examples including recent work with fermionic atoms is analogous. The first atomic fermionic condensate was created by a team led by Deborah S. Jin using potassium-40 atoms at the University of Colorado Boulder in 2003.

In quantum field theory, asymptotic freedom is a property of some gauge theories that causes interactions between particles to become asymptotically weaker as the energy scale increases and the corresponding length scale decreases.

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider is the first and one of only two operating heavy-ion colliders, and the only spin-polarized proton collider ever built. Located at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) in Upton, New York, and used by an international team of researchers, it is the only operating particle collider in the US. By using RHIC to collide ions traveling at relativistic speeds, physicists study the primordial form of matter that existed in the universe shortly after the Big Bang. By colliding spin-polarized protons, the spin structure of the proton is explored.

Lattice QCD is a well-established non-perturbative approach to solving the quantum chromodynamics (QCD) theory of quarks and gluons. It is a lattice gauge theory formulated on a grid or lattice of points in space and time. When the size of the lattice is taken infinitely large and its sites infinitesimally close to each other, the continuum QCD is recovered.

Hadronization is the process of the formation of hadrons out of quarks and gluons. There are two main branches of hadronization: quark-gluon plasma (QGP) transformation and colour string decay into hadrons. The transformation of quark-gluon plasma into hadrons is studied in lattice QCD numerical simulations, which are explored in relativistic heavy-ion experiments. Quark-gluon plasma hadronization occurred shortly after the Big Bang when the quark–gluon plasma cooled down to the Hagedorn temperature when free quarks and gluons cannot exist. In string breaking new hadrons are forming out of quarks, antiquarks and sometimes gluons, spontaneously created from the vacuum.

Quark matter or QCD matter refers to any of a number of hypothetical phases of matter whose degrees of freedom include quarks and gluons, of which the prominent example is quark-gluon plasma. Several series of conferences in 2019, 2020, and 2021 were devoted to this topic.

The QCD vacuum is the quantum vacuum state of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). It is an example of a non-perturbative vacuum state, characterized by non-vanishing condensates such as the gluon condensate and the quark condensate in the complete theory which includes quarks. The presence of these condensates characterizes the confined phase of quark matter.

In particle physics, the parton model is a model of hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, proposed by Richard Feynman. It is useful for interpreting the cascades of radiation produced from quantum chromodynamics (QCD) processes and interactions in high-energy particle collisions.

Color-glass condensate (CGC) is a type of matter theorized to exist in atomic nuclei when they collide at near the speed of light. During such collision, one is sensitive to the gluons that have very small momenta, or more precisely a very small Bjorken scaling variable. The small momenta gluons dominate the description of the collision because their density is very large. This is because a high-momentum gluon is likely to split into smaller momentum gluons. When the gluon density becomes large enough, gluon-gluon recombination puts a limit on how large the gluon density can be. When gluon recombination balances gluon splitting, the density of gluons saturate, producing new and universal properties of hadronic matter. This state of saturated gluon matter is called the color-glass condensate.

Color–flavor locking (CFL) is a phenomenon that is expected to occur in ultra-high-density strange matter, a form of quark matter. The quarks form Cooper pairs, whose color properties are correlated with their flavor properties in a one-to-one correspondence between three color pairs and three flavor pairs. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, the color-flavor-locked phase is the highest-density phase of three-flavor colored matter.

Quark–gluon plasma is an interacting localized assembly of quarks and gluons at thermal and chemical (abundance) equilibrium. The word plasma signals that free color charges are allowed. In a 1987 summary, Léon Van Hove pointed out the equivalence of the three terms: quark gluon plasma, quark matter and a new state of matter. Since the temperature is above the Hagedorn temperature—and thus above the scale of light u,d-quark mass—the pressure exhibits the relativistic Stefan-Boltzmann format governed by temperature to the fourth power and many practically massless quark and gluon constituents. It can be said that QGP emerges to be the new phase of strongly interacting matter which manifests its physical properties in terms of nearly free dynamics of practically massless gluons and quarks. Both quarks and gluons must be present in conditions near chemical (yield) equilibrium with their colour charge open for a new state of matter to be referred to as QGP.

The NA49 experiment was a particle physics experiment that investigated the properties of quark–gluon plasma. The experiment's synonym was Ions/TPC-Hadrons. It took place in the North Area of the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) at CERN from 1991-2002.

In theoretical particle physics, the gluon field strength tensor is a second order tensor field characterizing the gluon interaction between quarks.

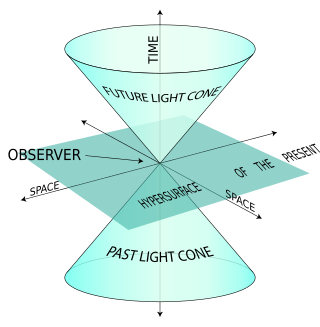

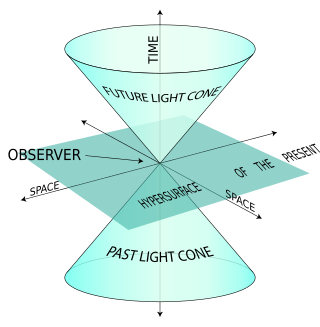

The light-front quantization of quantum field theories provides a useful alternative to ordinary equal-time quantization. In particular, it can lead to a relativistic description of bound systems in terms of quantum-mechanical wave functions. The quantization is based on the choice of light-front coordinates, where plays the role of time and the corresponding spatial coordinate is . Here, is the ordinary time, is a Cartesian coordinate, and is the speed of light. The other two Cartesian coordinates, and , are untouched and often called transverse or perpendicular, denoted by symbols of the type . The choice of the frame of reference where the time and -axis are defined can be left unspecified in an exactly soluble relativistic theory, but in practical calculations some choices may be more suitable than others. The basic formalism is discussed elsewhere.

Several hundred metals, compounds, alloys and ceramics possess the property of superconductivity at low temperatures. The SU(2) color quark matter adjoins the list of superconducting systems. Although it is a mathematical abstraction, its properties are believed to be closely related to the SU(3) color quark matter, which exists in nature when ordinary matter is compressed at supranuclear densities above ~ 0.5 1039 nucleon/cm3.

Larry D. McLerran is an American physicist and an academic. He is a professor of physics at the University of Washington.