The People's Party, also known as the Populist Party or simply the Populists, was a left-wing agrarian populist political party in the United States in the late 19th century. The Populist Party emerged in the early 1890s as an important force in the Southern and Western United States, but collapsed after it nominated Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 United States presidential election. A rump faction of the party continued to operate into the first decade of the 20th century, but never matched the popularity of the party in the early 1890s.

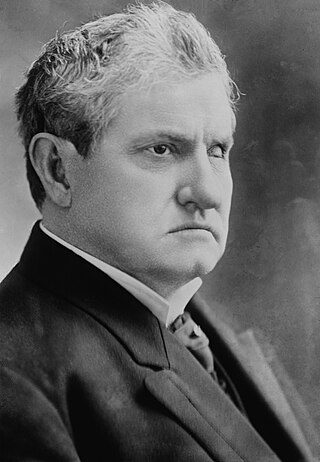

Benjamin Ryan Tillman was a politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A white supremacist who opposed civil rights for black Americans, Tillman led a paramilitary group of Red Shirts during South Carolina's violent 1876 election. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, he defended lynching, and frequently ridiculed black Americans in his speeches, boasting of having helped kill them during that campaign.

Thomas Edward Watson was an American Populist and white supremacist politician, attorney, newspaper editor, and writer from Georgia. In the 1890s Watson championed poor farmers as a leader of the Populist Party, articulating an agrarian political viewpoint while attacking business, bankers, railroads, Democratic President Grover Cleveland, and the Democratic Party. He was the nominee for vice president with Democrat William Jennings Bryan in 1896 on the Populist ticket.

Marion Butler was an American politician, farmer, and lawyer. He represented North Carolina in the United States Senate for one term, serving between 1895 and 1901. At the time, he was a leader of the North Carolina Populist Party, and also affiliated with the Democratic Party and the Republican Party at different points in his career. He was the older brother of George Edwin Butler.

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union among the white farmers of the South, the National Farmers' Alliance among the white and black farmers of the Midwest and High Plains, where the Granger movement had been strong, and the Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union, consisting of the African American farmers of the South.

Following the end of Reconstruction, African Americans created a broad-based independent political movement in the South: Black Populism.

The farmers' movement was, in American political history, the general name for a movement between 1867 and 1896. In this movement, there were three periods, popularly known as the Grange, Alliance and Populist movements.

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) (1934–1970) was founded as a civil farmer's union to organize tenant farmers in the Southern United States. Many such tenant farmer sharecroppers were Black descendants of former slaves.

The Ocala Demands was a platform for economic and political reform that was later adopted by the People's Party. In December, 1890, the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, more commonly known as the Southern Farmers' Alliance, its affiliate the Colored Farmers' Alliance, and the Farmers' Mutual Benefit Association met jointly in the Marion Opera House in Ocala, Florida, where they adopted the Ocala Demands.

George Washington Murray, born into slavery in South Carolina, gained education and worked as a teacher, farmer and politician. After serving as chairman of the Sumter County Republican Party, he was elected in the 1890s as a United States congressman from South Carolina. He was the only black member in the 53rd and 54th Congresses. Because South Carolina passed a constitution in 1895 that effectively disenfranchised blacks and crippled the Republican Party, Murray was the last Republican elected in the state for nearly 100 years. The next Republican, elected in 1980, was the result of a realignment of voters and parties.

Charles William Macune was the head of the Southern Farmers' Alliance from 1886 to December 1889 and editor of its official organ, the National Economist, until 1892. He is remembered as the father of a failed cooperative enterprise by the Farmers' Alliance in Dallas, Texas, and as the creator of the Sub-Treasury Plan, an effort to provide low-cost credit to farmers through a network of government-owned commodity warehouses.

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Carolina (1896), Florida (1902), Mississippi and Alabama, Texas (1905), Louisiana and Arkansas (1906), and Georgia (1900). Since winning the Democratic primary in the South almost always meant winning the general election, barring black and other minority voters meant they were in essence disenfranchised. Southern states also passed laws and constitutions with provisions to raise barriers to voter registration, completing disenfranchisement from 1890 to 1908 in all states of the former Confederacy.

The Socialist Party of Oklahoma was a semi-autonomous affiliate of the Socialist Party of America located in the Southwestern state of Oklahoma. One of the last states admitted to the Union, the area later incorporated into Oklahoma had been previously used for reservations to which indigenous Native American populations were deported, with the area formally divided after 1890 into two entities — an "Oklahoma Territory" in the West and an "Indian Territory" in the East.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

The role of African Americans in the agricultural history of the United States includes roles as the main work force when they were enslaved on cotton and tobacco plantations in the Antebellum South. After the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863-1865 most stayed in farming as very poor sharecroppers, who rarely owned land. They began the Great Migration to cities in the mid-20th century. About 40,000 are farmers today.

The 1892 Alabama gubernatorial election took place on August 1, 1892, in order to elect the governor of Alabama.

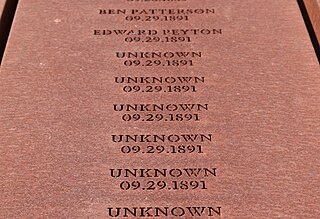

The cotton pickers' strike of 1891 was a labor action of African-American sharecroppers in Lee County, Arkansas in September, 1891. The strike led to open conflict between strikers and plantation owners, racially-motivated violence, and both a sheriff's posse and a lynching party. One plantation manager, two non-striking workers, and some twelve strikers were killed during the incident. Nine of those strikers were hung in a mass lynching on the evening of September 29.

The Black Belt in the American South refers to the social history, especially concerning slavery and black workers, of the geological region known as the Black Belt. The geology emphasizes the highly fertile black soil. Historically, the black belt economy was based on cotton plantations – along with some tobacco plantation areas along the Virginia-North Carolina border. The valuable land was largely controlled by rich whites, and worked by very poor, primarily black slaves who in many counties constituted a majority of the population. Generally the term is applied to a larger region than that defined by its geology.

Populism in the United States reaches back to the Presidency of Andrew Jackson in the 1830s and to the People's Party in the 1890s. It has made a resurgence in modern-day politics in not only the United States but also democracies around the world. Populism is an approach to politics which views "the people" as being opposed to "the elite" and is often used as a synonym of anti-establishment; as an ideology, it transcends the typical divisions of left and right and has become more prevalent in the US with the rise of disenfranchisement and apathy toward the establishment. The definition of populism is a complex one as due to its mercurial nature; it has been defined by many different scholars with different focuses, including political, economic, social, and discursive features. Populism is often split into two variants in the US, one with a focus on culture and the other that focuses on economics.

"Radicalism" or "radical liberalism" was a political ideology in the 19th century United States aimed at increasing political and economic equality. The ideology was rooted in a belief in the power of the ordinary man, political equality, and the need to protect civil liberties.