Related Research Articles

Microcredit is the extension of very small loans (microloans) to impoverished borrowers who typically lack collateral, steady employment, and a verifiable credit history. It is designed to support entrepreneurship and alleviate poverty. Many recipients are illiterate, and therefore unable to complete paperwork required to get conventional loans. As of 2009 an estimated 74 million people held microloans that totaled nearly US$40 billion. Grameen Bank reports that repayment success rates are between 95 and 98 percent. The first economist who had invented the idea of microloans was Jonathan Swift in the 1720s. Microcredit is part of microfinance, which provides a wider range of financial services, especially savings accounts, to the poor. Modern microcredit is generally considered to have originated with the Grameen Bank founded in Bangladesh in 1983 by their current Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus. Many traditional banks subsequently introduced microcredit despite initial misgivings. The United Nations declared 2005 the International Year of Microcredit. As of 2012, microcredit is widely used in developing countries and is presented as having "enormous potential as a tool for poverty alleviation."

Microfinance consists of financial services targeting individuals and small businesses (SMEs) who lack access to conventional banking and related services.

Grameen Bank is a microfinance, specialized community development bank founded in Bangladesh. It provides small loans to the impoverished without requiring collateral.

BRAC is an international development organisation based in Bangladesh. In order to receive foreign donations, BRAC was subsequently registered under the NGO Affairs Bureau of the Government of Bangladesh. BRAC is the largest non-governmental development Organisation in the world, in terms of the number of employees as of September 2016. Established by Sir Fazle Hasan Abed in 1972 after the independence of Bangladesh, BRAC is present in all 64 districts of Bangladesh as well as 16 other countries in Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

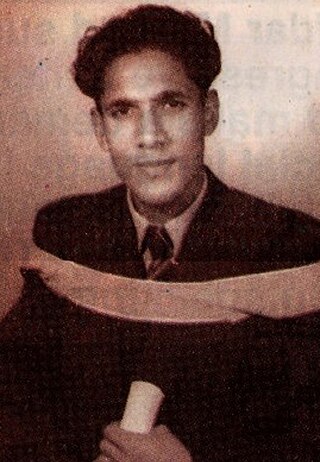

Akhter Hameed Khan was a Pakistani development practitioner and social scientist. He promoted participatory rural development in Pakistan and other developing countries, and widely advocated community participation in development. His particular contribution was the establishment of a comprehensive project for rural development, the Comilla Model (1959). It earned him the Ramon Magsaysay Award from the Philippines and an honorary Doctorate of law from Michigan State University.

The Orangi Pilot Project collectively designates three Pakistani non-governmental organisations working together, having emerged from a socially innovative project carried out in 1980s in the squatter areas of Orangi, Karachi, Pakistan. It was initiated by Akhtar Hameed Khan and implemented by Perween Rahman. Innovative methods were used to provide adequate low cost sanitation, health, housing and microfinance facilities.

The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) is an All India Development Financial Institution (DFI) and an apex Supervisory Body for overall supervision of Regional Rural Banks, State Cooperative Banks and District Central Cooperative Banks in India. It was established under the NABARD Act 1981 passed by the Parliament of India. It is fully owned by Government of India and functions under the Department of Financial Services (DFS) under the Ministry of Finance.

The Association for Social Advancement is a non-governmental organisation based in Bangladesh which provides microcredit financing.

Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) (Bengali: বাংলাদেশ পল্লী উন্নয়ন একাডেমী started its journey on 27 May 1959 as a Training, Research and Action Research institute in rural development. The founder director of this academy dedicated to the leadership of Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan, some researchers carried out continuous experiments with rural people and developed some model programs for rural development in this country. In the early sixties, the problems that were prevalent in rural areas were identified. The priorities of these programs are:

Village banking is a microcredit and saving methodology whereby financial services are administered locally in a community bank rather than in a centralized commercial bank. Village banking has its roots in ancient cultures and was most recently adopted for use by micro-finance institutions (MFIs) as a way to control costs. Early village banking methods were innovated by Grameen Bank and then later developed by groups such as FINCA International founder John Hatch. Among US-based non-profit agencies there are at least 31 microfinance institutions (MFIs) that have collectively created over 800 village banking programs in at least 90 countries. And in many of these countries there are host-country MFIs—sometimes dozens—that are village banking practitioners as well. The latest developments globally can be seen in Southeast Asia, where digitization is pacing fast to reach rural areas with hybrid on- and offline solutions.

Solidarity lending is a lending practice where small groups borrow collectively and group members encourage one another to repay. It is an important building block of microfinance.

The Grameen family of organizations has grown beyond Grameen Bank into a multi-faceted group of both commercial and non-profit ventures. It was first established by Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning founder of Grameen Bank. Most of the organizations in the Grameen group have central offices at the Grameen Bank Complex in Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Grameen Bank started to diversify in the late 1980s when it began attending to unutilized or underutilized fishing ponds, as well as irrigation pumps like deep tubewells. In 1989, these diversified interests started growing into separate organizations, as the fisheries project became Grameen Fisheries Foundation and the irrigation project became Grameen Krishi Foundation.

Comilla Victoria Government College, mostly known as Comilla Victoria College, is a government college in Comilla, Bangladesh. It is one of the oldest and prestigious colleges in Comilla as well as in the Chittagong division. The degree and honours branch of the college is located in Dharmapur area of Cumilla district. The college was named after Queen Victoria, once the Queen of United Kindom and British Raj.

Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA) is the central body to monitor and supervise microfinance operations of non-governmental organizations of the Republic of Bangladesh. It was created by the Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh under the Microcredit Regulatory Authority Act. License from the Authority is mandatory to operate microfinance operation in Bangladesh as an NGO.

Microcredit for water supply and sanitation is the application of microcredit to provide loans to small enterprises and households in order to increase access to an improved water source and sanitation in developing countries.

The SIDBI foundation for Microcredit (SFMC) is an Indian financial division that provides bulk loans to microfinance institutions (MFIs) in India. It is a division of Indian governments Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI). In practice, it acts as an oversight over MFIs which are the intermediaries between the retail borrowers consisting of poor people and individual borrowers living in rural areas or urban slums and the public sector development finance institutions.

Shoaib Sultan Khan NI is one of the pioneers of rural development programmes in Pakistan. As a CSP Officer, he worked with the Government of Pakistan for 25 years, later on he served Geneva based Aga Khan Foundation for 12 years, then UNICEF and UNDP for 14 years. Since his retirement, he has been involved with the Rural Support Programmes (RSPs) of Pakistan full-time, on voluntary basis. Today, the Rural Support Programmes have helped form 297,000 community organisations in 110 districts including two Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan.

The impact of microcredit is the study of microcredit and its impact on poverty reduction which is a subject of much controversy. Proponents state that it reduces poverty through higher employment and higher incomes. This is expected to lead to improved nutrition and improved education of the borrowers' children. Some argue that microcredit empowers women. In the US and Canada, it is argued that microcredit helps recipients to graduate from welfare programs. Critics say that microcredit has not increased incomes, but has driven poor households into a debt trap, in some cases even leading to suicide. They add that the money from loans is often used for durable consumer goods or consumption instead of being used for productive investments, that it fails to empower women, and that it has not improved health or education.

Kashf Foundation is a non-profit organization, founded by Roshaneh Zafar in 1996. Kashf is regarded as the first microfinance institution (MFI) of Pakistan that uses village banking methodology in microcredit to alleviate poverty by providing affordable financial and non-financial services to low income households - particularly for women, to build their capacity and enhance their economic role. With headquarters in Lahore, Punjab, Kashf have regional offices in five major cities and over 200 branches across Pakistan.

Waliullah Patwar was a Bangladeshi academic who received the Independence Award, the country's highest civilian award.

References

- ↑ "Allama Mashriqi and Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan: Two Legends of Pakistan", by Nasim Yousaf, ISBN 1-4010-9097-4 (2003)http://www.nasimyousaf.info Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Akhter Hameed Khan, Director's Speech in First Annual Report, Comilla, 1960.

- ↑ 2007, Nasim Yousaf,"Dr. Akhter Hameed Khan – The Pioneer of Microcredit"http://www.akhtar-hameed-khan.8m.com/drkhan-microcredit.pdf Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Works of Akhter Hameed Khan. Volume I-III. Compiled by the Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development, Kothbari, Comilla. (1983)

- ↑ The Works of Akhter Hameed Khan. Volume II. p. 190.

- ↑ Arthur F Raper, Rural Development in Action: The Comprehensive Experiment at Comilla, East Pakistan, Cornell University Press: Ithaca (1970). p. vii. SBN 8014-0570-X

- ↑ Akhter Hameed Khan, Works of Akhter Hameed Khan, Vol. II, p. 190.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Aditee Nag, Let Grassroots Speak: People’s Participation Self-Help Groups and NGO’s in Bangladesh, University Press Ltd., Dhaka, 1989, p. 50.

- ↑ Akhter Hameed Khan, Works of Akhter Hameed Khan, Vol. II, p. 127.

- ↑ Akhter Hameed Khan, Works of Akhter Hameed Khan, Vol. III.

- ↑ Comilla Model at Banglapedia

- ↑ MA Quddus (ed.) Rural Development in Bangladesh, Comilla, 1993

- ↑ The Works of Akhter Hameed Khan. Volume II, pp. 190–91

- ↑ The Works of Akhter Hameed Khan. Volume II, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Aditee Nag Chowdhury, Let Grassroots Speak, p. 54.

- ↑ Aditee Nag Chowdhury, Let Grassroots Speak, p. 53

- ↑ Asif Dowla & Dipal Barua. The Poor Always Pay Back: The Grameen II Story Kumarian Press Inc., Bloomfield, Connecticut, 2006, p. 18

- ↑ Khandker, Shahidur R., Fighting Poverty with Microcredit: Experience in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Edition, The University Press Ltd., Dhaka, 1999, pp. 17–18