Related Research Articles

The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy, which was formed in 1861 by states that had seceded from the Union. The central conflict leading to war was a dispute over whether slavery should be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prohibited from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

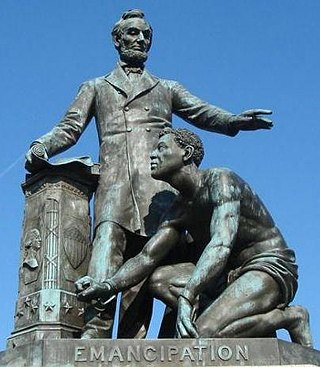

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to "be received into the armed service of the United States". The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted following the American Civil War.

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate slaves around the world.

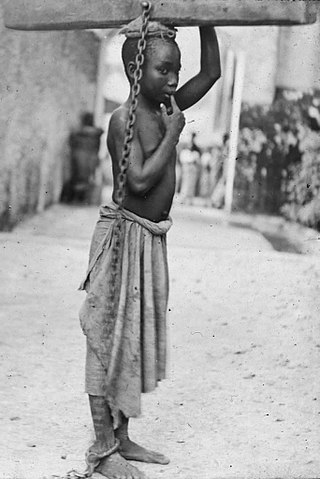

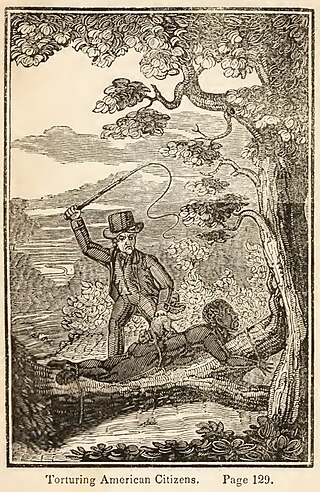

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

In the American Civil War (1861–65), the border states or the Border South were four, later five, slave states in the Upper South that primarily supported the Union. They were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, and after 1863, the new state of West Virginia. To their north they bordered free states of the Union, and all but Delaware bordered slave states of the Confederacy to their south.

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states to be politically imperative that the number of free states not exceed the number of slave states, so new states were admitted in slave–free pairs. There were, nonetheless, some slaves in most free states up to the 1840 census, and the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution, as implemented by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, provided that a slave did not become free by entering a free state and must be returned to his or her owner.

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery in the United States is one of the most discussed aspects of his life. Lincoln frequently expressed his moral opposition to slavery in public and private. "I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong," he stated. "I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." However, the question of what to do about it and how to end it, given that it was so firmly embedded in the nation's constitutional framework and in the economy of much of the country, even though concentrated in only the Southern United States, was complex and politically challenging. In addition, there was the unanswered question, which Lincoln had to deal with, of what would become of the four million slaves if liberated: how they would earn a living in a society that had almost always rejected them or looked down on their very presence.

The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War is a biography of Abraham Lincoln written by Thomas J. DiLorenzo, a former professor of economics at Loyola University Maryland, in 2002. He was severely critical of Lincoln's United States presidency.

Compensated emancipation was a method of ending slavery, under which the enslaved person's owner received compensation from the government in exchange for manumitting the slave. This could be monetary, and it could allow the owner to retain the slave for a period of labor as an indentured servant. In practice, cash compensation rarely was equal to the slave's market value.

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of slaves have differed vastly in different systems of slavery in different times and places.

Historiography examines how the past has been viewed or interpreted. Historiographic issues about the American Civil War include the name of the war, the origins or causes of the war, and President Abraham Lincoln's views and goals regarding slavery.

Junius P. Rodriguez is a professor of history at Eureka College in Eureka, Illinois, who has been the general editor of multiple major reference books on the history of slavery in the United States and the world, as well as related topics such as black history and abolitionism. His work on the history of slavery was acclaimed as "outstanding" by other scholars and by librarians, who have recommended it as part of the core collection for every academic library and many public libraries as well.

Slavery played the central role during the American Civil War. The primary catalyst for secession was slavery, especially Southern political leaders' resistance to attempts by Northern antislavery political forces to block the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Slave life went through great changes, as the South saw Union Armies take control of broad areas of land. During and before the war, enslaved people played an active role in their own emancipation, and thousands of enslaved people escaped from bondage during the war.

This timeline of events leading to the American Civil War is a chronologically ordered list of events and issues that historians recognize as origins and causes of the American Civil War. These events are roughly divided into two periods: the first encompasses the gradual build-up over many decades of the numerous social, economic, and political issues that ultimately contributed to the war's outbreak, and the second encompasses the five-month span following the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States in 1860 and culminating in the capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861.

An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 37th Cong., Sess. 2, ch. 54, 12 Stat. 376, known colloquially as the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act or simply Compensated Emancipation Act, was a law that ended slavery in the District of Columbia, while providing slave owners who remained loyal to the United States in the then-ongoing Civil War to petition for compensation. Although not written by him, the act was signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. April 16 is now celebrated in the city as Emancipation Day.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

"Boston Hymn" is a poem by the American essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson composed the poem in late 1862 and read it publicly in Boston Music Hall on January 1, 1863. It commemorates the Emancipation Proclamation issued earlier that day by President Abraham Lincoln, tying it and the broader campaign for the abolition of slavery to the Puritan notion of sacred destiny for America.

In the District of Columbia, the slave trade was legal from its creation until it was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming was a major factor in the retrocession of the Virginia part of the District back to Virginia in 1847. Thus the large slave-trading businesses in Alexandria, such as Franklin & Armfield, could continue their operations in Virginia, where slavery was more secure.

From the late 18th to the mid-19th century, various states of the United States allowed the enslavement of human beings, most of whom had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade or were their descendants. The institution of chattel slavery was established in North America in the 16th century under Spanish colonization, British colonization, French colonization, and Dutch colonization.

References

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, "Drafts of a Bill for Compensated Emancipation in Delaware," in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 5 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), pp. 29-31.

- ↑ David Goldfield, America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation, 2011, p. 248.

- ↑ William MacDonald, ed., Select Statutes and other Documents Illustrative of the History of the United States, 1861-1898, 1903, p. 34.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Slavery in the United States: a social, political, and historical encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2007, vol. 2, pp. 238-9. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781851095445. Archived from the original on 2019-12-26. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery Archived 2020-01-01 at the Wayback Machine . Volume 1; Volume 7 Junius P. Rodriguez ABC-CLIO, 1997. 805 pages.

- ↑ History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 Archived 2019-12-29 at the Wayback Machine . James Ford Rhodes, The Macmillan Company, 1899.

- ↑ Buying Freedom: The Ethics and Economics of Slave Redemption Archived 2019-12-28 at the Wayback Machine . Anthony Appiah, Martin Bunzl Princeton University Press, 2007.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Mary (1963). ""I Held George Washington's Horse": Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 63/65: 221–229. ISSN 0897-9049. JSTOR 40067361.

- ↑ Palmer, R.R.; Colton, Joel (1995). A History of the Modern World. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 572–573. ISBN 978-0070408265.

- ↑ Robert E. Wright, Fubarnomics (Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus, 2010), 83–116.

- ↑ Gunderson, Gerald (1974). "The Origin of the American Civil War". Journal of Economic History . 34 (4): 915–950. doi:10.1017/S0022050700089361. JSTOR 2116615. S2CID 154869722.

- 1 2 Ransom, Roger (August 24, 2001). Whaples, Robert (ed.). "Economics of the Civil War". EH.Net Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 16, 2014.