The Baroque is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s. It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo and Neoclassical styles. It was encouraged by the Catholic Church as a means to counter the simplicity and austerity of Protestant architecture, art, and music, though Lutheran Baroque art developed in parts of Europe as well.

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's goals and methods. Although the two activities are closely related, literary critics are not always, and have not always been, theorists.

The term Metaphysical poets was coined by the critic Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of 17th-century English poets whose work was characterised by the inventive use of conceits, and by a greater emphasis on the spoken rather than lyrical quality of their verse. These poets were not formally affiliated and few were highly regarded until 20th century attention established their importance.

Luis de Góngora y Argote was a Spanish Baroque lyric poet and a Catholic prebendary for the Church of Córdoba. Góngora and his lifelong rival, Francisco de Quevedo, are widely considered the most prominent Spanish poets of all time. His style is characterized by what was called culteranismo, also known as Gongorismo. This style apparently existed in stark contrast to Quevedo's conceptismo, though Quevedo was highly influenced by his older rival from whom he may have isolated "conceptismo" elements.

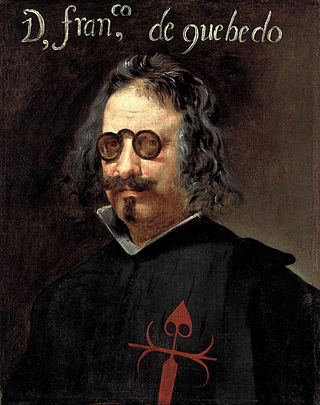

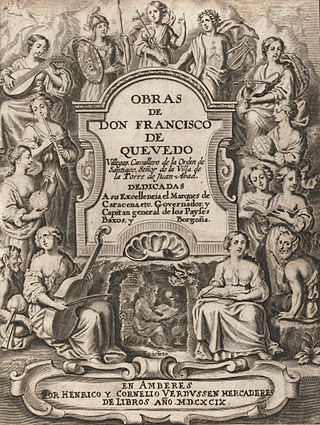

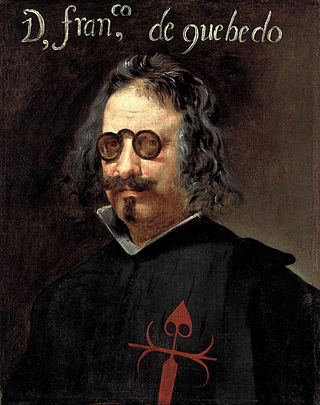

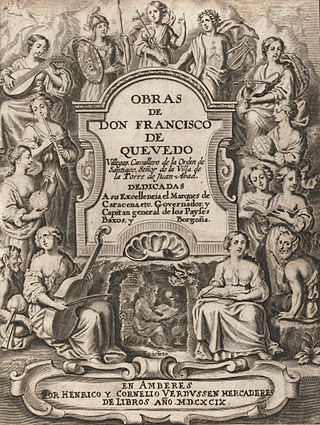

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Santibáñez Villegas, Knight of the Order of Santiago was a Spanish nobleman, politician and writer of the Baroque era. Along with his lifelong rival, Luis de Góngora, Quevedo was one of the most prominent Spanish poets of the age. His style is characterized by what was called conceptismo. This style existed in stark contrast to Góngora's culteranismo.

Spanish literature generally refers to literature written in the Spanish language within the territory that presently constitutes the Kingdom of Spain. Its development coincides and frequently intersects with that of other literary traditions from regions within the same territory, particularly Catalan literature, Galician intersects as well with Latin, Jewish, and Arabic literary traditions of the Iberian peninsula. The literature of Spanish America is an important branch of Spanish literature, with its own particular characteristics dating back to the earliest years of Spain’s conquest of the Americas.

This article concerns poetry in Spain.

Baltasar Gracián y Morales, S.J., better known as Baltasar Gracián, was a Spanish Jesuit and Baroque prose writer and philosopher. He was born in Belmonte, near Calatayud (Aragón). His writings were lauded by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of the most prominent architectural styles in the Western world. The prevailing styles of architecture in most of Europe for the previous two centuries, Renaissance architecture and Baroque architecture, already represented partial revivals of the Classical architecture of ancient Rome and ancient Greek architecture, but the Neoclassical movement aimed to strip away the excesses of Late Baroque and return to a purer, more complete, and more authentic classical style, adapted to modern purposes.

Marinism is the name now given to an ornate, witty style of poetry and verse drama written in imitation of Giambattista Marino (1569–1625), following in particular La Lira and L'Adone.

Giambattista Marino was an Italian poet who was born in Naples. He is most famous for his epic L'Adone.

Culteranismo is a stylistic movement of the Baroque period of Spanish history that is also commonly referred to as Gongorismo. It began in the late 16th century with the writing of Luis de Góngora and lasted through the 17th century.

The Atheneo de Grandesa is an emblem book written in the Catalan language by Josep Romaguera and published in 1681 by the printer Joan Jolis in Barcelona. It contains 15 engravings by an unknown artist.

Spanish Baroque literature is the literature written in Spain during the Baroque, which occurred during the 17th century in which prose writers such as Baltasar Gracián and Francisco de Quevedo, playwrights such as Lope de Vega, Tirso de Molina, Calderón de la Barca and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, or the poetic production of the aforementioned Francisco de Quevedo, Lope de Vega and Luis de Góngora reached their zenith. Spanish Baroque literature is a period of writing which begins approximately with the first works of Luis de Góngora and Lope de Vega, in the 1580s, and continues into the late 17th century.

La Fábula de Polifemo y Galatea, or simply the Polifemo, is a literary work written by Spanish poet Luis de Góngora y Argote. The poem, though borrowing heavily from prior literary sources of Greek and Roman Antiquity, attempts to go beyond the established versions of the myth by reconfiguring the narrative structure handed down by Ovid. Through the incorporation of highly innovative poetic techniques, Góngora effectively advances the background story of Acis and Galatea’s infatuation as well as the jealousy of the Cyclops Polyphemus.

Emanuele Tesauro was an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, literary theorist, dramatist, Marinist poet, and historian.

Torquato Accetto was an Italian writer born in Trani. He is particularly remembered for his book on conformity and hypocrisy, titled Della dissimulazione onesta.

Francesco Fulvio Frugoni (1620–1686), was an Italian Baroque poet, writer and literary critic, one of the masters of Italian conceptismo.

The Accademia dei Gelati was a learned society of intellectuals, mainly noblemen, that significantly influenced the cultural and political life of Baroque Bologna. It is considered one of the most important 17th-century Italian academies.