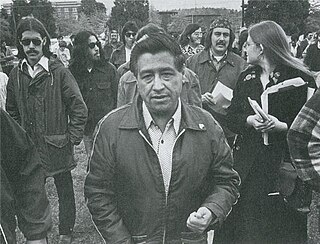

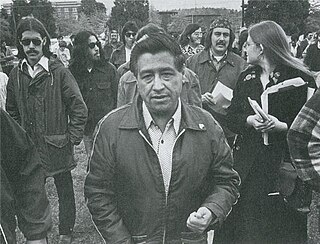

The Brown Berets is a pro-Chicano paramilitary organization that emerged during the Chicano Movement in the late 1960s. David Sanchez and Carlos Montes co-founded the group modeled after the Black Panther Party. The Brown Berets was part of the Third World Liberation Front. It worked for educational reform, farmworkers' rights, and against police brutality and the Vietnam War. It also sought to separate the American Southwest from the control of the United States government.

Chicanismo emerged as the cultural consciousness behind the Chicano Movement. The central aspect of Chicanismo is the identification of Chicanos with their Indigenous American roots to create an affinity with the notion that they are native to the land rather than immigrants. Chicanismo brought a new sense of nationalism for Chicanos that extended the notion of family to all Chicano people. Barrios, or working-class neighborhoods, became the cultural hubs for the people. It created a symbolic connection to the ancestral ties of Mesoamerica and the Nahuatl language through the situating of Aztlán, the ancestral home of the Aztecs, in the southwestern United States. Chicanismo also rejected Americanization and assimilation as a form of cultural destruction of the Chicano people, fostering notions of Brown Pride. Xicanisma has been referred to as an extension of Chicanismo.

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation. Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Ester Hernández is a California Bay Area Chicana visual artist recognized for her prints and pastels focusing on farm worker rights, cultural, political, and Chicana feminist issues. Hernández' was an activist in the Chicano Arts Movement in the 1960's and also made art pieces that focus on issues of social justice, civil rights, women's rights, and the Farm Worker Movement.

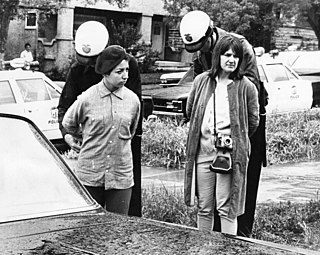

The East Los Angeles Walkouts or Chicano Blowouts were a series of 1968 protests by Chicano students against unequal conditions in Los Angeles Unified School District high schools. The first walkout occurred on March 5, 1968. The students who organized and carried out the protests were primarily concerned with the quality of their education. This movement, which involved thousands of students in the Los Angeles area, was identified as "the first major mass protest against racism undertaken by Mexican-Americans in the history of the United States".

Partido Nacional de La Raza Unida was a Hispanic political party centered on Chicano (Mexican-American) nationalism. It was created in 1970 and became prominent throughout Texas and Southern California. It was started to combat growing inequality and dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party that was typically supported by Mexican-American voters. After its establishment in Texas, the party launched electoral campaigns in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and California, though it only secured official party status for statewide races in Texas. It did poorly in the 1978 Texas elections and dissolved when leaders and members dropped out.

Las Adelitas de Aztlán was a short-lived Mexican American female civil rights organization that was created by Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes in 1970. Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes were all former members of the Brown Berets, another Mexican American Civil rights organization that had operated concurrently during the 1960s and 1970s in the California area. The founders left the Brown Berets due to enlarging gender discrepancies and disagreements that caused much alienation amongst their female members. The Las Adelitas De Aztlan advocated for Mexican-American Civil rights, better conditions for workers, protested police brutality and advocated for women's rights for the Latino community. The name of the organization was a tribute to Mexican female soldiers or soldaderas that fought during the Mexican Revolution of the early twentieth century.

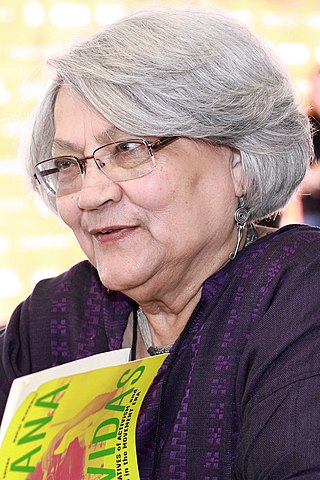

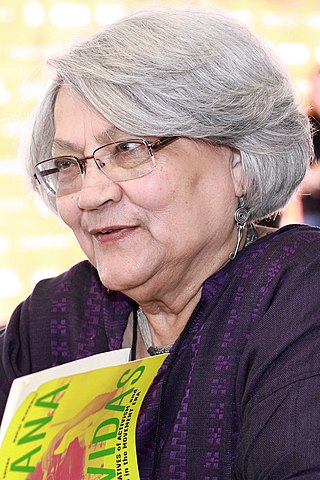

Martha P. Cotera is a librarian, writer, and influential activist of both the Chicano Civil Rights Movement and the Chicana Feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Her two most notable works are Diosa y Hembra: The History and Heritage of Chicanas in the U.S. and The Chicana Feminist. Cotera was one of six women featured in a documentary, Las Mujeres de la Caucus Chicana, which recounts the experiences of some of the Chicana participants of the 1977 National Women's Conference in Houston, Texas.

Chicana literature is a form of literature that has emerged from the Chicana Feminist movement. It aims to redefine Chicana archetypes, in an effort to provide positive models for Chicanas. Chicana writers redefine their relationships with what Gloria Anzaldúa has called "Las Tres Madres" of Mexican culture, by depicting them as feminist sources of strength and compassion.

Maria Eugenia Cotera is an American author, researcher, and professor. Maria Cotera is an associate professor at the University of Texas. She started as a researcher and writer at the Chicana Research and Learning Center. In 1989 she helped produce "Crystal City: A Twenty Year Reflection," a documentary about young women in the 1969 Chicano student walkout in Crystal City, Texas.

The Chicano Art Movement represents groundbreaking movements by Mexican-American artists to establish a unique artistic identity in the United States. Much of the art and the artists creating Chicano Art were heavily influenced by Chicano Movement which began in the 1960s.

Anna Nieto-Gomez is a scholar, journalist, and author who was a central part of the early Chicana movement. She founded the feminist journal, Encuentro Femenil, in which she and other Chicana writers addressed issues affecting the Latina community, such as childcare, reproductive rights, and the feminization of poverty.

Alicia Escalante is a Chicana activist who was active during the Chicano Movement. She was the founder and chair of the East Los Angeles Chicana Welfare Rights Organization from 1967 to 1978.

Hijas de Cuauhtémoc was a student Chicana feminist newspaper founded in 1971 by Anna Nieto-Gómez and Adelaida Castillo while both were students at California State University, Long Beach.

The Chicana/Latina Foundation (CLF) is a non-profit organization that promotes professional and leadership development of Latinas. The Foundation's mission is to empower Chicanas/Latinas through college scholarships, personal growth, educational, technology, cultural arts, and professional advancement.

Dorinda Moreno is an American Chicana activist, feminist and writer.

A Mexican American is a resident of the United States who is of Mexican descent. Mexican American-related topics include the following:

Mujeres Activas en Letras Y Cambio Social (MALCS) is an inclusive organization of Chicana, Latina, Native American and gender non-conforming academics, students, and activists. MALCS focuses on recognizing the hard work of contributors to the organization, giving women access to higher education, and educating society about the issues they face. MALCS was established in 1982 at the University of California, Davis after noticing no change was being made during the Chicano Movement despite their activism efforts. To continue their efforts in unifying women, they provide membership opportunities and benefits such as access to their summer institute and their peer-reviewed journal: Chicana/Latina Studies which talks about the experiences of Latina women. This organization helps bring them together to share their thoughts, opinions, and information about things they want to work on, current issues, or anything. They also bring together their research and community involvement to create social change. It is a safe space for everyone to uplift and support one another.

Chicano Youth Liberation Conference was a conference held in Denver, Colorado in March 1969. It is also called the Denver Youth Conference. This was the first large scale gathering of Chicano/a youth to discuss issues of oppression, discrimination, and injustice. Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales and the Crusade for Justice were the main organizers, and they drafted and presented "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan" at the conference, which played a major part in the national Chicano movement.