Boudica or Boudicca was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. She is considered a British national heroine and a symbol of the struggle for justice and independence.

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of Britannia after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Gaul was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of 494,000 km2 (191,000 sq mi). According to Julius Caesar, who took control of the region on behalf of the Roman Republic, Gaul was divided into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania.

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by AD 87, when the Stanegate was established. The conquered territory became the Roman province of Britannia. Attempts to conquer northern Britain (Caledonia) in the following centuries were not successful.

Caratacus was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the Catuvellauni tribe, who resisted the Roman conquest of Britain.

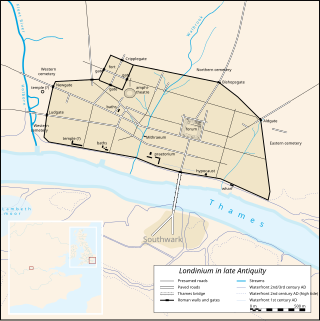

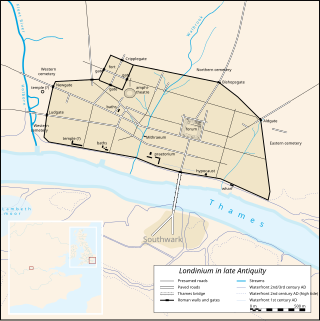

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. Most twenty-first century historians think that it was originally a settlement established shortly after the Claudian invasion of Britain, on the current site of the City of London around 47–50 AD, but some defend an older view that the city originated in a defensive enclosure constructed during the Claudian invasion in 43 AD. Its earliest securely-dated structure is a timber drain of 47 AD. It sat at a key ford at the River Thames which turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century.

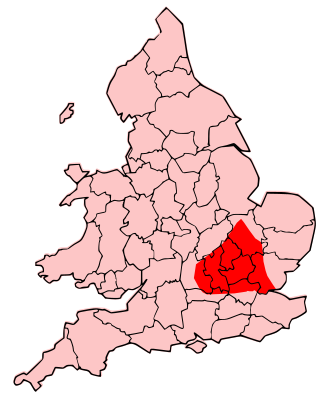

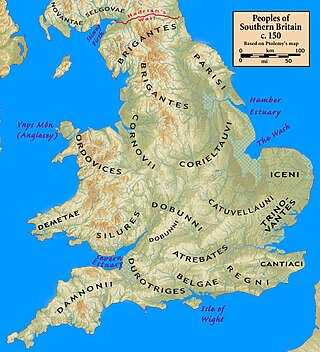

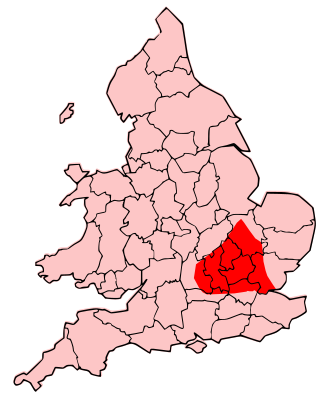

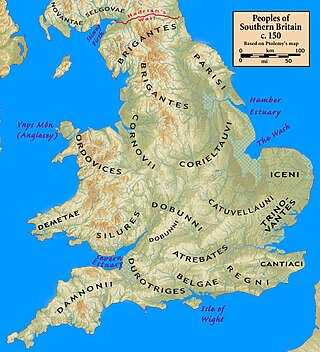

The Iceni or Eceni were an ancient tribe of eastern Britain during the Iron Age and early Roman era. Their territory included present-day Norfolk and parts of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, and bordered the area of the Corieltauvi to the west, and the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes to the south. In the Roman period, their capital was Venta Icenorum at modern-day Caistor St Edmund.

The Catuvellauni were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

Adrian Keith Goldsworthy is a British historian and novelist who specialises in ancient Roman history.

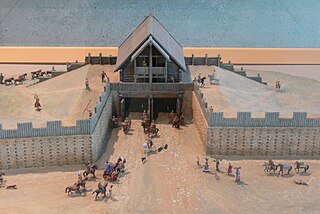

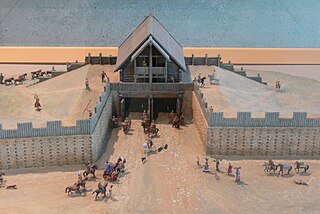

An oppidum is a large fortified Iron Age settlement or town. Oppida are primarily associated with the Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread across Europe, stretching from Britain and Iberia in the west to the edge of the Hungarian plain in the east. These settlements continued to be used until the Romans conquered Southern and Western Europe. Many subsequently became Roman-era towns and cities, whilst others were abandoned. In regions north of the rivers Danube and Rhine, such as most of Germania, where the populations remained independent from Rome, oppida continued to be used into the 1st century AD.

The Roman client kingdoms in Britain were native tribes which chose to align themselves with the Roman Empire because they saw it as the best option for self-preservation or for protection from other hostile tribes. Alternatively, the Romans created some client kingdoms when they felt influence without direct rule was desirable. Client kingdoms were ruled by client kings. In Latin these kings were referred to as rex sociusque et amicus, which translates to "king, ally, and friend". The type of relationships between client kingdoms and Rome was reliant on the individual circumstances in each kingdom.

Greece in the Roman era describes the Roman conquest of ancient Greece as well as that of the Greek people and the areas they inhabited and ruled historically. It covers the periods when Greece was dominated first by the Roman Republic and then by the Roman Empire.

The borders of the Roman Empire, which fluctuated throughout the empire's history, were realised as a combination of military roads and linked forts, natural frontiers and man-made fortifications which separated the lands of the empire from the countries beyond.

This timeline of ancient history lists historical events of the documented ancient past from the beginning of recorded history until the Early Middle Ages. Prior to this time period, prehistory civilizations were pre-literate and did not have written language.

Scotland during the Roman Empire refers to the protohistorical period during which the Roman Empire interacted within the area of modern Scotland. Despite sporadic attempts at conquest and government between the first and fourth centuries AD, most of modern Scotland, inhabited by the Caledonians and the Maeatae, was not incorporated into the Roman Empire with Roman control over the area fluctuating.

The Roman conquest of Anglesey refers to two separate invasions of Anglesey in North West Wales that occurred during the early decades of the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century CE. The first invasion of North Wales began after the Romans had subjugated much of southern Britain. It was led by the Provincial governor of Britannia, Suetonius Paulinus, who led a successful assault on the island in 60–61 CE, but had to withdraw because of the Boudican revolt. In 77 CE, Gnaeus Julius Agricola's thorough subjugation of the island left it under Roman rule until the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century CE. The invasions occurred because Anglesey, which was recorded in Latin as Mona was a place of resistance to Roman rule because it was an important centre for the Celtic Druids and their religious practices.

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. While they were reported to have been literate, they are believed to have been prevented by doctrine from recording their knowledge in written form. Their beliefs and practices are attested in some detail by their contemporaries from other cultures, such as the Romans and the Greeks.

The frontier of the Roman Empire in Britain is sometimes styled Limes Britannicus by authors for the boundaries, including fortifications and defensive ramparts, that were built to protect Roman Britain. These defences existed from the 1st to the 5th centuries AD and ran through the territory of present-day England, Scotland and Wales.

The historiography of Romanisation is the study of the methods, sources, techniques, and concepts used by historians when examining the process of Romanisation. The Romanisation process affected different regions differently, meaning that there is no singular definition for the concept, however it is generally defined as the spread of Roman civilisation and culture throughout Italy and the provinces as an indication of a historical process, such as acculturation, integration and assimilation. Generally, the Romanisation process affected language, economics, cultural structures, family norms and material culture. Rome introduced its culture mainly through conquest, colonisation, trade, and the resettlement of retired soldiers.

The Boudican revolt was an armed uprising by native Celtic Britons against the Roman Empire during the Roman conquest of Britain. It took place circa AD 60–61 in the Roman province of Britain, and it was led by Boudica, the Queen of the Iceni tribe. The uprising was motivated by the Romans' failure to honour an agreement they had made with Boudica's husband, Prasutagus, regarding the succession of his kingdom upon his death, and by the brutal mistreatment of Boudica and her daughters by the occupying Romans.