Related Research Articles

In law, a judgment is a decision of a court regarding the rights and liabilities of parties in a legal action or proceeding. Judgments also generally provide the court's explanation of why it has chosen to make a particular court order.

The Federal Court of Justice is the highest court of civil and criminal jurisdiction in Germany. Its primary responsibility is the final appellate review of decisions by lower courts for errors of law. While, legally, a decision by the Federal Court of Justice is only binding with respect to the individual case in which it enters, de facto the court's interpretation of the law is followed by lower courts with almost no exception. Decisions handed down by the Federal Court of Justice can only be vacated by the Federal Constitutional Court for violating a provision of the German constitution, the Basic Law.

Vriend v Alberta [1998] 1 S.C.R. 493 is an important Supreme Court of Canada case that determined that a legislative omission can be the subject of a Charter violation. The case involved a dismissal of a teacher because of his sexual orientation and was an issue of great controversy during that period.

Freedom of religion in Germany is guaranteed by article 4 of the German constitution. This states that "the freedom of religion, conscience and the freedom of confessing one's religious or philosophical beliefs are inviolable. Uninfringed religious practice is guaranteed." In addition, article 3 states that "No one may be prejudiced or favored because of his gender, his descent, his race, his language, his homeland and place of origin, his faith or his religious or political views." Any person or organization can call the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany for free help.

A dissenting opinion is an opinion in a legal case in certain legal systems written by one or more judges expressing disagreement with the majority opinion of the court which gives rise to its judgment.

Following Bahrain's independence from the British in 1971, the government of Bahrain embarked on an extended period of political suppression under a 1974 State Security Law shortly after the adoption of the country's first formal Constitution in 1973. Overwhelming objections to state authority resulted in the forced dissolution of the National Assembly by Amir Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa and the suspension of the Constitution until 2001. The State Security Law of 1974 was a law used by the government of Bahrain to crush political unrest from 1974 until 2001. It was during this period that the worst human rights violations and torture were said to have taken place. The State Security Law contained measures permitting the government to arrest and imprison individuals without trial for a period of up to three years for crimes relating to state security. A subsequent Decree to the 1974 Act invoked the establishment of State Security Courts, adding to the conditions conducive to the practice of arbitrary arrest and torture. The deteriorating human rights situation in Bahrain is reported to have reached its height in the mid-1990s when thousands of men, women and children were illegally detained, reports of torture and ill-treatment of detainees were documented, and trials fell short of international standards.

In most legal systems of the Spanish-speaking world, the writ of amparo is a remedy for the protection of constitutional rights, found in certain jurisdictions. The amparo remedy or action is an effective and inexpensive instrument for the protection of individual rights.

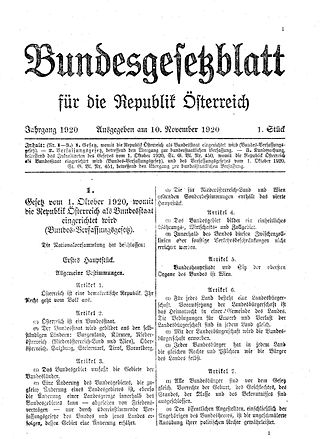

The judiciary of Austria is the system of courts, prosecution and correction of the Republic of Austria as well as the branch of government responsible for upholding the rule of law and administering justice. The judiciary is independent of the other two branches of government and is committed to guaranteeing fair trials and equality before the law. It has broad and effective powers of judicial review.

The Constitutional Court in Austria is the tribunal responsible for judicial review.

Plattform "Ärzte für das Leben" v. Austria (10126/82) was a landmark case decided by the European Court of Human Rights in 1988.

Fundamental Rights in the Federal Republic of Germany are a set of rights guaranteed to everyone in Germany and partially to German people only through their Federal Constitution, the Grundgesetz and the constitutions of some of the States of Germany. In the Federal Constitution, the majority of the Grundrechte are contained in the first title, Articles 1 to 19 of the Grundgesetz (GG). These rights have constitutional status, binding each of the country's constitutional institutions. In the event that these rights are violated and a remedy is denied by other courts, the constitution provides for an appeal to the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht).

Threshold issues are legal requirements in Singapore administrative law that must be satisfied by applicants before their claims for judicial review of acts or decisions of public authorities can be dealt with by the High Court. These include showing that they have standing to bring cases, and that the matters are amenable to judicial review and justiciable by the Court.

The remedies available in a Singapore constitutional claim are the prerogative orders – quashing, prohibiting and mandatory orders, and the order for review of detention – and the declaration. As the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore is the supreme law of Singapore, the High Court can hold any law enacted by Parliament, subsidiary legislation issued by a minister, or rules derived from the common law, as well as acts and decisions of public authorities, that are inconsistent with the Constitution to be void. Mandatory orders have the effect of directing authorities to take certain actions, prohibiting orders forbid them from acting, and quashing orders invalidate their acts or decisions. An order for review of detention is sought to direct a party responsible for detaining a person to produce the detainee before the High Court so that the legality of the detention can be established.

The Federal Constitutional Court is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law of Germany. Since its inception with the beginning of the post-World War II republic, the court has been located in the city of Karlsruhe, which is also the seat of the Federal Court of Justice.

Re Wünsche Handelsgesellschaft BVerfGE 73, 339, is a German constitutional law and EU law case, popularly known as Solange II, concerning the conflict of law between the German national legal system and European Union law.

Transgender rights in the Federal Republic of Germany are regulated by the Transsexuellengesetz since 1980, and indirectly affected by other laws like the Abstammungsrecht. The law initially required transgender people to undergo sex-reassignment surgery in order to have key identity documents changed. This has since been declared unconstitutional. The German government has pledged to replace the Transsexuellengesetz with the Selbstbestimmungsgesetz, which would remove the financial and bureaucratic hurdles necessary for legal gender and name changes. Discrimination protections on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation vary across Germany, but discrimination in employment and the provision of goods and services is in principle banned countrywide.

The European and Austrian constitutions endow the Austrian court system with broad powers of judicial review. All Austrian courts are charged with verifying that the statutes and ordinances they are about to apply conform to European Union law, and to refuse to apply them if not. A specialized Constitutional Court checks statutes for compliance with the Austrian constitution and executive ordinances for compliance with Austrian law in general.

Ingve Björn Stjerna is a German lawyer, known for having filed in 2017 a constitutional complaint with the German Federal Constitutional Court against the ratification of the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court in Germany. In April 2017, his complaint led the German Constitutional Court to ask the President of Germany to suspend the ratification of the Agreement. His complaint, which was assigned court case reference 2 BvR 739/17, was upheld by the Court.

Stephan Harbarth is the president of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (Bundesverfassungsgericht), former German lawyer and politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). From 2009 until 2018 he served as member of the Bundestag. On 22 November 2018 he was elected to the Federal Constitutional Court by the Bundestag. He succeeded Ferdinand Kirchhof and serves in the court's first senate. On 23 November 2018, one day after his election to the court, he was elected vice president of the Federal Constitutional Court by the Bundesrat. In this capacity, he is chairman of the first senate.

The Prostitution Act is a federal law in Germany that regulates the legal status of prostitution as a service in order to improve the legal and social situation of prostitutes. The law was promulgated on 20 December 2001 and has been enforced since 1 January 2002. At the same time the Strafgesetzbuch §180a and §181a (pimping) were amended to allow for employment of prostitutes, as long as they were not exploited.

References

- ↑ Sec. 95, para. 3, sentence 1, Bundesverfassungsgerichtsgesetz - enacted pursuant to Art. 94, para. 2, sentence 1, GG.

- ↑ Refer to sec. 90 et seq., BVerfGG - available in English at Gesetze im Internet.de, https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bverfgg/englisch_bverfgg.html#p0400

- ↑ Art. 93, GG - available in English via Gesetze im Internet.de at https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0520

- ↑ Sec. 23 para. 1, BVerfGG.

- ↑ Sec. 92, paras. 1 and 3, BVerfGG.

- ↑ Sec. 92, paras. 1 and 3, BVerfGG.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at paras. 108 and 116.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 96.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 101.

- 1 2 Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 119.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 200.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 230.

- ↑ Hillgruber & Goos 2020, at para. 285.