Related Research Articles

Chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid called the mobile phase, which carries it through a system on which a material called the stationary phase is fixed. The different constituents of the mixture have different affinities for the stationary phase. The different molecules stay longer or shorter on the stationary phase, depending on their interactions with its surface sites. So, they travel at different apparent velocities in the mobile fluid, causing them to separate. The separation is based on the differential partitioning between the mobile and the stationary phases. Subtle differences in a compound's partition coefficient result in differential retention on the stationary phase and thus affect the separation.

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity.

Lysis is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a lysate. In molecular biology, biochemistry, and cell biology laboratories, cell cultures may be subjected to lysis in the process of purifying their components, as in protein purification, DNA extraction, RNA extraction, or in purifying organelles.

Spectrophotometry is a branch of electromagnetic spectroscopy concerned with the quantitative measurement of the reflection or transmission properties of a material as a function of wavelength. Spectrophotometry uses photometers, known as spectrophotometers, that can measure the intensity of a light beam at different wavelengths. Although spectrophotometry is most commonly applied to ultraviolet, visible, and infrared radiation, modern spectrophotometers can interrogate wide swaths of the electromagnetic spectrum, including x-ray, ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and/or microwave wavelengths.

A protein complex or multiprotein complex is a group of two or more associated polypeptide chains. Different polypeptide chains may have different functions. This is distinct from a multienzyme complex, in which multiple catalytic domains are found in a single polypeptide chain.

Protein purification is a series of processes intended to isolate one or a few proteins from a complex mixture, usually cells, tissues or whole organisms. Protein purification is vital for the specification of the function, structure and interactions of the protein of interest. The purification process may separate the protein and non-protein parts of the mixture, and finally separate the desired protein from all other proteins. Separation of one protein from all others is typically the most laborious aspect of protein purification. Separation steps usually exploit differences in protein size, physico-chemical properties, binding affinity and biological activity. The pure result may be termed protein isolate.

Fractionation is a separation process in which a certain quantity of a mixture is divided during a phase transition, into a number of smaller quantities (fractions) in which the composition varies according to a gradient. Fractions are collected based on differences in a specific property of the individual components. A common trait in fractionations is the need to find an optimum between the amount of fractions collected and the desired purity in each fraction. Fractionation makes it possible to isolate more than two components in a mixture in a single run. This property sets it apart from other separation techniques.

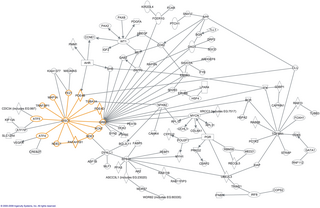

In molecular biology, an interactome is the whole set of molecular interactions in a particular cell. The term specifically refers to physical interactions among molecules but can also describe sets of indirect interactions among genes.

Affinity chromatography is a method of separating a biomolecule from a mixture, based on a highly specific macromolecular binding interaction between the biomolecule and another substance. The specific type of binding interaction depends on the biomolecule of interest; antigen and antibody, enzyme and substrate, receptor and ligand, or protein and nucleic acid binding interactions are frequently exploited for isolation of various biomolecules. Affinity chromatography is useful for its high selectivity and resolution of separation, compared to other chromatographic methods.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) is the technique of precipitating a protein antigen out of solution using an antibody that specifically binds to that particular protein. This process can be used to isolate and concentrate a particular protein from a sample containing many thousands of different proteins. Immunoprecipitation requires that the antibody be coupled to a solid substrate at some point in the procedure.

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts of high specificity established between two or more protein molecules as a result of biochemical events steered by interactions that include electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding and the hydrophobic effect. Many are physical contacts with molecular associations between chains that occur in a cell or in a living organism in a specific biomolecular context.

Macromolecular docking is the computational modelling of the quaternary structure of complexes formed by two or more interacting biological macromolecules. Protein–protein complexes are the most commonly attempted targets of such modelling, followed by protein–nucleic acid complexes.

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), is a form of liquid chromatography that is often used to analyze or purify mixtures of proteins. As in other forms of chromatography, separation is possible because the different components of a mixture have different affinities for two materials, a moving fluid and a porous solid. In FPLC the mobile phase is an aqueous solution, or "buffer". The buffer flow rate is controlled by a positive-displacement pump and is normally kept constant, while the composition of the buffer can be varied by drawing fluids in different proportions from two or more external reservoirs. The stationary phase is a resin composed of beads, usually of cross-linked agarose, packed into a cylindrical glass or plastic column. FPLC resins are available in a wide range of bead sizes and surface ligands depending on the application.

Protein A is a 49 kDa surface protein originally found in the cell wall of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. It is encoded by the spa gene and its regulation is controlled by DNA topology, cellular osmolarity, and a two-component system called ArlS-ArlR. It has found use in biochemical research because of its ability to bind immunoglobulins. It is composed of five homologous Ig-binding domains that fold into a three-helix bundle. Each domain is able to bind proteins from many mammalian species, most notably IgGs. It binds the heavy chain within the Fc region of most immunoglobulins and also within the Fab region in the case of the human VH3 family. Through these interactions in serum, where IgG molecules are bound in the wrong orientation, the bacteria disrupts opsonization and phagocytosis.

Thermostability is the quality of a substance to resist irreversible change in its chemical or physical structure, often by resisting decomposition or polymerization, at a high relative temperature.

The Strep-tag® system is a method which allows the purification and detection of proteins by affinity chromatography. The Strep-tag II is a synthetic peptide consisting of eight amino acids (Trp-Ser-His-Pro-Gln-Phe-Glu-Lys). This peptide sequence exhibits intrinsic affinity towards Strep-Tactin®, a specifically engineered streptavidin, and can be N- or C- terminally fused to recombinant proteins. By exploiting the highly specific interaction, Strep-tagged proteins can be isolated in one step from crude cell lysates. Because the Strep-tag elutes under gentle, physiological conditions it is especially suited for generation of functional proteins.

The Streptavidin-Binding Peptide (SBP)-Tag is a 38-amino acid sequence that may be engineered into recombinant proteins. Recombinant proteins containing the SBP-Tag bind to streptavidin and this property may be utilized in specific purification, detection or immobilization strategies.

Numerous key discoveries in biology have emerged from studies of RNA, including seminal work in the fields of biochemistry, genetics, microbiology, molecular biology, molecular evolution and structural biology. As of 2010, 30 scientists have been awarded Nobel Prizes for experimental work that includes studies of RNA. Specific discoveries of high biological significance are discussed in this article.

The term macromolecular assembly (MA) refers to massive chemical structures such as viruses and non-biologic nanoparticles, cellular organelles and membranes and ribosomes, etc. that are complex mixtures of polypeptide, polynucleotide, polysaccharide or other polymeric macromolecules. They are generally of more than one of these types, and the mixtures are defined spatially, and with regard to their underlying chemical composition and structure. Macromolecules are found in living and nonliving things, and are composed of many hundreds or thousands of atoms held together by covalent bonds; they are often characterized by repeating units. Assemblies of these can likewise be biologic or non-biologic, though the MA term is more commonly applied in biology, and the term supramolecular assembly is more often applied in non-biologic contexts. MAs of macromolecules are held in their defined forms by non-covalent intermolecular interactions, and can be in either non-repeating structures, or in repeating linear, circular, spiral, or other patterns. The process by which MAs are formed has been termed molecular self-assembly, a term especially applied in non-biologic contexts. A wide variety of physical/biophysical, chemical/biochemical, and computational methods exist for the study of MA; given the scale of MAs, efforts to elaborate their composition and structure and discern mechanisms underlying their functions are at the forefront of modern structure science.

The human interactome is the set of protein–protein interactions that occur in human cells. The sequencing of reference genomes, in particular the Human Genome Project, has revolutionized human genetics, molecular biology, and clinical medicine. Genome-wide association study results have led to the association of genes with most Mendelian disorders, and over 140 000 germline mutations have been associated with at least one genetic disease. However, it became apparent that inherent to these studies is an emphasis on clinical outcome rather than a comprehensive understanding of human disease; indeed to date the most significant contributions of GWAS have been restricted to the “low-hanging fruit” of direct single mutation disorders, prompting a systems biology approach to genomic analysis. The connection between genotype and phenotype remain elusive, especially in the context of multigenic complex traits and cancer. To assign functional context to genotypic changes, much of recent research efforts have been devoted to the mapping of the networks formed by interactions of cellular and genetic components in humans, as well as how these networks are altered by genetic and somatic disease.

References

- ↑ Golemis, Erica (2002). Protein–protein interactions: a molecular cloning manual. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-628-1.

- ↑ Schon, Eric A.; Pon, Liza A. (2001). Mitochondria . Methods in Cell Biology. 65. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 0-12-544169-X.

- ↑ Stumpf MP, Thorne T, de Silva E, Stewart R, An HJ, Lappe M, Wiuf C (May 2008). "Estimating the size of the human interactome". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (19): 6959–64. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.6959S. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708078105 . PMC 2383957 . PMID 18474861.