In music, the tonic is the first scale degree of the diatonic scale and the tonal center or final resolution tone that is commonly used in the final cadence in tonal classical music, popular music, and traditional music. In the movable do solfège system, the tonic note is sung as do. More generally, the tonic is the note upon which all other notes of a piece are hierarchically referenced. Scales are named after their tonics: for instance, the tonic of the C major scale is the note C.

Arcangelo Corelli was an Italian composer and violinist of the Baroque era. His music was key in the development of the modern genres of sonata and concerto, in establishing the preeminence of the violin, and as the first coalescing of modern tonality and functional harmony.

In music theory, the key of a piece is the group of pitches, or scale, that forms the basis of a musical composition in Western classical music, art music, and pop music.

Tonality or key: Music which uses the notes of a particular scale is said to be "in the key of" that scale or in the tonality of that scale.

Sonata form is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th century.

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance below the tonic as the dominant is above the tonic – in other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdominant. It also happens to be the note one step below the dominant. In the movable do solfège system, the subdominant note is sung as fa.

Resolution in western tonal music theory is the move of a note or chord from dissonance to a consonance.

Recitative is a style of delivery in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms and delivery of ordinary speech. Recitative does not repeat lines as formally composed songs do. It resembles sung ordinary speech more than a formal musical composition.

In Western musical theory, a cadence is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards. A harmonic cadence is a progression of two or more chords that concludes a phrase, section, or piece of music. A rhythmic cadence is a characteristic rhythmic pattern that indicates the end of a phrase. A cadence can be labeled "weak" or "strong" depending on the impression of finality it gives.

In music, the submediant is the sixth degree of a diatonic scale. The submediant is named thus because it is halfway between the tonic and the subdominant or because its position below the tonic is symmetrical to that of the mediant above.

In music, the subtonic is the degree of a musical scale which is a whole step below the tonic note. In a major key, it is a lowered, or flattened, seventh scale degree. It appears as the seventh scale degree in the natural minor and descending melodic minor scales but not in the major scale. In major keys, the subtonic sometimes appears in borrowed chords. In the movable do solfège system, the subtonic note is sung as te.

Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 is among the three famous piano sonatas of his middle period ; it was composed during 1804 and 1805, and perhaps 1806, and Beethoven dedicated it to cellist and his friend, Count Franz Brunswick. The first edition was published in February 1807 in Vienna.

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh; thus it is a major triad together with a minor seventh. It is often denoted by the letter name of the chord root and a superscript "7". In most cases, dominant seventh chord are built on the fifth degree of the major scale. An example is the dominant seventh chord built on G, written as G7, having pitches G–B–D–F:

In Classical music theory, a Neapolitan chord is a major chord built on the lowered (flattened) second (supertonic) scale degree. In Schenkerian analysis, it is known as a Phrygian II, since in minor scales the chord is built on the notes of the corresponding Phrygian mode.

The Andalusian cadence is a term adopted from flamenco music for a chord progression comprising four chords descending stepwise – a iv–III–II–I progression with respect to the Phrygian mode or i–VII–VI–V progression with respect to the Aeolian mode (minor). It is otherwise known as the minor descending tetrachord. Traceable back to the Renaissance, its effective sonorities made it one of the most popular progressions in classical music.

In jazz and jazz harmony, the chord progression from iv7 to ♭VII7 to I (the tonic or "home" chord) has been nicknamed the backdoor progression or the backdoor ii-V, as described by jazz theorist and author Jerry Coker. This name derives from an assumption that the normal progression to the tonic, the ii-V-I turnaround (ii-V7 to I, see also authentic cadence) is, by inference, the "front door", a metaphor suggesting that this is the main route to the tonic.

Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 2 No. 1, was written in 1795 and dedicated to Joseph Haydn. It was published simultaneously with his second and third piano sonatas in 1796.

A minor major seventh chord, or minor/major seventh chord is a seventh chord composed of a root, minor third, perfect fifth, and major seventh. It can be viewed as a minor triad with an additional major seventh. When using popular-music symbols, it is denoted by e.g. m(M7). For example, the minor major seventh chord built on A, written as e.g. Am(M7), has pitches A-C-E-G♯:

In classical music theory, the English cadence is a contrapuntal pattern particular to the authentic or perfect cadence. It features a flattened seventh scale degree against the dominant chord, which in the key of C would be B♭ and G–B♮–D.

The Symphony No. 21 in A major, Hoboken I/21, was composed by Joseph Haydn around the year 1764. The symphony’s movements have unusual structures that make their form hard to identify. The parts that pertain to sonata form are often hard to recognize immediately and are often identified “only in retrospect.”

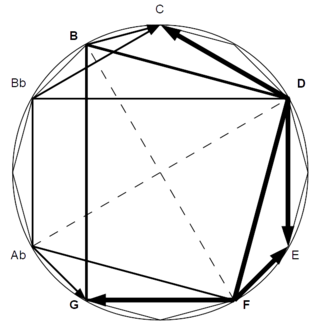

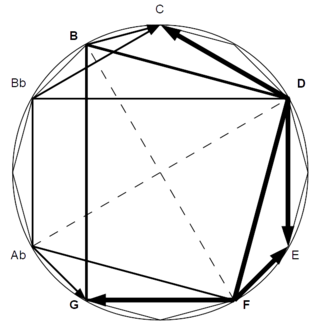

In music, the dominant is the fifth scale degree of the diatonic scale. It is called the dominant because it is second in importance to the first scale degree, the tonic. In the movable do solfège system, the dominant note is sung as "So(l)".