Related Research Articles

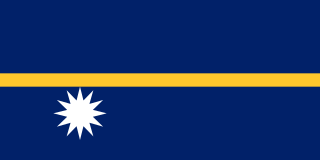

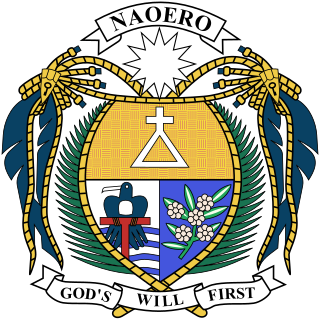

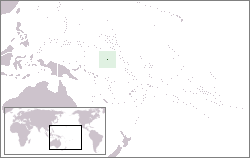

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Micronesia, part of Oceania in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba of Kiribati, about 300 km (190 mi) to the east.

The history of human activity in Nauru, an island country in the Pacific Ocean, began roughly 3,000 years ago when clans settled the island.

The politics of Nauru take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Nauru is the head of government of the executive branch. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the parliament. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Hammer DeRoburt was the first President of the Republic of Nauru, and ruled the country for most of its first twenty years of independence.

Reverend Philip Adam Delaporte was a German-born American Protestant missionary who ran a mission on Nauru with his wife from 1899 until 1915. During this time he translated numerous texts from German into Nauruan including the Bible and a hymnal. He was also one of the first to create a written form for the Nauruan dialect, published in a Nauruan-German dictionary.

Angam Day is a holiday recognised in the Republic of Nauru. It is celebrated yearly on 26 October.

Timothy Detudamo was a Nauruan politician and linguist. He served as Head Chief of Nauru from 1930 until his death in 1953.

Australian rules football in Nauru dates back to the 1910s. Australian rules football became the national sport of Nauru after its independence in 1968. Today, its national participation rate is over 30%, the highest in the world.

Marcus Ajemada Stephen is a Nauruan politician and former sportsperson who previously was a member of the Cabinet of Nauru, and who served as President of Nauru from December 2007 to November 2011. The son of Nauruan parliamentarian Lawrence Stephen, Stephen was educated at St Bedes College and RMIT University in Victoria, Australia. Initially playing Australian rules football, he opted to pursue the sport of weightlifting, in which he represented Nauru at the Summer Olympics and Commonwealth Games between 1990 and 2002, winning seven Commonwealth gold medals.

The British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC) was a board of Australian, British, and New Zealand representatives who managed extraction of phosphate from Christmas Island, Nauru, and Banaba from 1920 until 1981.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Nauru:

Nauruan nationality law is regulated by the 1968 Constitution of Nauru, as amended; the Naoero Citizenship Act of 2017, and its revisions; custom; and international agreements entered into by the Nauruan government. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Nauru. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nauruan nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in the Nauru or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Nauruan nationality. Naturalization is only available to those with some connection to the country, such as the spouse of a citizen; no amount of time living in Nauru will, by itself, make one eligible for naturalization.

Raymond Gadabu was a Nauruan politician who served as Head Chief between 1953 and 1955.

The Japanese occupation of Nauru was the period of three years during which Nauru, a Pacific island which at that time was under Australian administration, was occupied by the Japanese military as part of its operations in the Pacific War during World War II. With the onset of the war, the islands that flanked Japan's South Seas possessions became of vital concern to Japanese Imperial General Headquarters, and in particular to the Imperial Navy, which was tasked with protecting Japan's outlying Pacific territories.

Elections for the Local Government Council were held for the first time in Nauru on 15 December 1951.

Elections for the Local Government Council were held in Nauru on 10 December 1955.

Elections for the Legislative Council for the Territory of Nauru were held for the first and only time on 22 January 1966.

Austin Bernicke was a Nauruan politician. He was a member of the first Local Government Council in 1951, then a member of Parliament after it was established in 1966, serving until his death in 1977. He also served as a cabinet minister from 1968 until 1976.

The 1948 Nauru riots occurred when Chinese labourers employed on the phosphate mines refused to leave the island. At the time, Nauru was dominated by Australia as a United Nations trust territory, with New Zealand and the UK as co-trustees.

The Nauru Local Government Council was a legislative body in Nauru. It was first established in 1951, when Nauru was a United Nations trust territory, as a successor to the Council of Chiefs. It continued to exist until 1992, when it was dissolved in favor of the Nauru Island Council.

References

- ↑ Storr, Cait (2020). International Status in the Shadow of Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1108498500.

- 1 2 3 Pollock, Nancy J. (2014). "Nauru Phosphate History and the Resource Curse Narrative". Journal de la Société des Océanistes (138–139): 96, 52. doi: 10.4000/jso.7055 . Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Viviani, Nancy (1970). Nauru Phosphate and Political Progress (PDF). Australian National University. pp. 60–61, 93–97, 104.

- ↑ "Nauru v. Australia" (PDF). International Court of Justice. December 1990. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ↑ Ntumy, Michael A. (1993). "Nauru". South Pacific Islands Legal Systems. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9780824814380.