English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties against one or more parties in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used with respect to a civil action brought by a plaintiff who requests a legal remedy or equitable remedy from a court. The defendant is required to respond to the plaintiff's complaint or else risk default judgment. If the plaintiff is successful, judgment is entered in favor of the defendant. A variety of court orders may be issued in connection with or as part of the judgment to enforce a right, award damages or restitution, or impose a temporary or permanent injunction to prevent an act or compel an act. A declaratory judgment may be issued to prevent future legal disputes.

Admiralty courts, also known as maritime courts, are courts exercising jurisdiction over all maritime contracts, torts, injuries, and offences.

The courts of England and Wales, supported administratively by His Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service, are the civil and criminal courts responsible for the administration of justice in England and Wales.

In the history of the courts of England and Wales, the Judicature Acts were a series of Acts of Parliament, beginning in the 1870s, which aimed to fuse the hitherto split system of courts of England and Wales. The first two Acts were the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 and the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1875, with a further series of amending acts.

The court system of Canada forms the country's judiciary, formally known as "The King on the Bench", which interprets the law and is made up of many courts differing in levels of legal superiority and separated by jurisdiction. Some of the courts are federal in nature, while others are provincial or territorial.

The legal system of Singapore is based on the English common law system. Major areas of law – particularly administrative law, contract law, equity and trust law, property law and tort law – are largely judge-made, though certain aspects have now been modified to some extent by statutes. However, other areas of law, such as criminal law, company law and family law, are almost completely statutory in nature.

The Supreme Court of New South Wales is the highest state court of the Australian State of New South Wales. It has unlimited jurisdiction within the state in civil matters, and hears the most serious criminal matters. Whilst the Supreme Court is the highest New South Wales court in the Australian court hierarchy, an appeal by special leave can be made to the High Court of Australia.

The Supreme Court of Singapore is a set of courts in Singapore, comprising the Court of Appeal and the High Court. It hears both civil and criminal matters. The Court of Appeal hears both civil and criminal appeals from the High Court. The Court of Appeal may also decide a point of law reserved for its decision by the High Court, as well as any point of law of public interest arising in the course of an appeal from a court subordinate to the High Court, which has been reserved by the High Court for decision of the Court of Appeal.

The High Court of Singapore is the lower division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the upper division being the Court of Appeal. The High Court consists of the chief justice and the judges of the High Court. Judicial Commissioners are often appointed to assist with the Court's caseload. There are two specialist commercial courts, the Admiralty Court and the Intellectual Property Court, and a number of judges are designated to hear arbitration-related matters. In 2015, the Singapore International Commercial Court was established as part of the Supreme Court of Singapore, and is a division of the High Court. The other divisions of the high court are the General Division, the Appellate Division, and the Family Division. The seat of the High Court is the Supreme Court Building.

The Court of Appeal of Singapore is the highest court in the judicial system of Singapore. It is the upper division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the lower being the High Court. The Court of Appeal consists of the chief justice, who is the president of the Court, and the judges of the Court of Appeal. The chief justice may ask judges of the High Court to sit as members of the Court of Appeal to hear particular cases. The seat of the Court of Appeal is the Supreme Court Building.

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, and highcourt of appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of a supreme court are not subject to further review by any other court. Supreme courts typically function primarily as appellate courts, hearing appeals from decisions of lower trial courts, or from intermediate-level appellate courts.

The Governors Court was a court established in the early 19th century in the colony of New South Wales. The colony was subsequently to become a state of Australia in 1901. The court had jurisdiction to deal with civil disputes where the amount in dispute in the colony was not more than £50 sterling. The Supreme Court of New South Wales replaced the court in 1823 when the Supreme Court was created by the Third Charter of Justice.

The Lieutenant Governor's Court was a court established in the early 19th century in the colony of Van Diemen's Land which subsequently became Tasmania, a state of Australia. The court had jurisdiction to deal with civil disputes where the amount in dispute was not more than £50 sterling in the colony. The establishment of the court was the first practical civil court in the settlement. This was an important first step in improving the resolution of civil disputes in the settlement. The Supreme Court of Van Diemen's Land eventually replaced it in 1823 when the court's charter was revoked by the Third Charter of Justice.

The Supreme Court of Civil Judicature of New South Wales was a court established in the early 19th century in the colony of New South Wales. The colony was subsequently to become a state of Australia in 1901. The court had jurisdiction to deal with civil disputes where the amount in dispute in the colony was more than £50 sterling. The Supreme Court of New South Wales replaced the court in 1823 when the Supreme Court was created by the Third Charter of Justice.

The Vice Admiralty Court was a prerogative court established in the late 18th century in the colony of New South Wales, which was to become a state of Australia. A vice admiralty court is in effect an admiralty court. The word "vice" in the name of the court denoted that the court represented the Lord Admiral of the United Kingdom. In English legal theory, the Lord Admiral, as vice-regal of the monarch, was the only person who had authority over matters relating to the sea. The Lord Admiral would authorize others as his deputies or surrogates to act. Generally, he would appoint a person as a judge to sit in the Court as his surrogate. By appointing Vice-Admirals in the colonies, and by constituting courts as Vice-Admiralty Courts, the terminology recognized that the existence and superiority of the "mother" court in the United Kingdom. Thus, the "vice" tag denoted that whilst it was a separate court, it was not equal to the "mother" court. In the case of the New South Wales court, a right of appeal lay back to the British Admiralty Court, which further reinforced this superiority. In all respects, the court was an Imperial court rather than a local Colonial court.

The Federal Court of Malaysia is the highest court and the final appellate court in Malaysia. It is housed in the Palace of Justice in Putrajaya. The court was established during Malaya's independence in 1957 and received its current name in 1994.

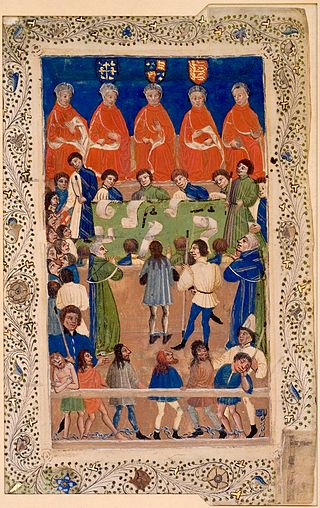

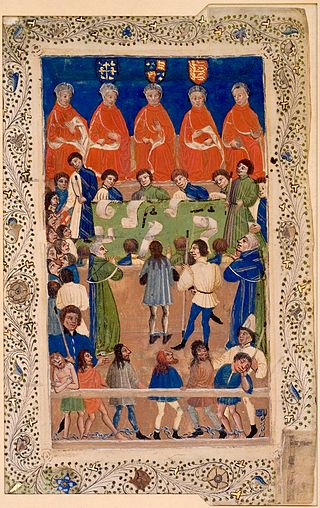

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the curia regis, the King's Bench initially followed the monarch on his travels. The King's Bench finally joined the Court of Common Pleas and Exchequer of Pleas in Westminster Hall in 1318, making its last travels in 1421. The King's Bench was merged into the High Court of Justice by the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873, after which point the King's Bench was a division within the High Court. The King's Bench was staffed by one Chief Justice and usually three Puisne Justices.

The Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip was an historical division of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, exercising the jurisdiction of that court within the Port Phillip District of New South Wales. It consisted of a single Resident Judge. It existed from 1840 until 1852, when, following the separation of the Port Phillip District to form the Colony of Victoria, it was replaced by the Supreme Court of Victoria.

Accounts of the Indigenous law governing dispute resolution in the area now called Ontario, Canada, date from the early to mid-17th century. French civil law courts were created in Canada, the colony of New France, in the 17th century, and common law courts were first established in 1764. The territory was then known as the province of Quebec.