Related Research Articles

A currency is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins. A more general definition is that a currency is a system of money in common use within a specific environment over time, especially for people in a nation state. Under this definition, the British Pound sterling (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$) are examples of (government-issued) fiat currencies. Currencies may act as stores of value and be traded between nations in foreign exchange markets, which determine the relative values of the different currencies. Currencies in this sense are either chosen by users or decreed by governments, and each type has limited boundaries of acceptance; i.e., legal tender laws may require a particular unit of account for payments to government agencies.

In economics, cash is money in the physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins.

Seigniorage, also spelled seignorage or seigneurage, is the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it. The term can be applied in two ways:

In economics and law, fungibility is the property of a good or a commodity whose individual units are essentially interchangeable. In legal terms, this affects how legal rights apply to such items. Fungible things can be substituted for each other; for example, a $100 bill (note) is considered entirely equivalent to twenty $5 bills (notes), and therefore a person who borrows $100 in the form of a $100 bill can repay the money with twenty $5 bills. There is no requirement to return the same $100 bill. Non-fungible items are not substitutable in the same manner.

A banknote—also called a bill, paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commercial banks, which were legally required to redeem the notes for legal tender when presented to the chief cashier of the originating bank. These commercial banknotes only traded at face value in the market served by the issuing bank. Commercial banknotes have primarily been replaced by national banknotes issued by central banks or monetary authorities.

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in payment of a debt extinguishes the debt. There is no obligation on the creditor to accept the tendered payment, but the act of tendering the payment in legal tender discharges the debt.

The pound sterling is the official currency of the United Kingdom, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, British Antarctic Territory, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and Tristan da Cunha.

The Indian rupee is the official currency in India. The rupee is subdivided into 100 paise. The issuance of the currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India. The Reserve Bank manages currency in India and derives its role in currency management on the basis of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

Nemo dat quod non habet, literally meaning "no one can give what they do not have", is a legal rule, sometimes called the nemo dat rule, that states that the purchase of a possession from someone who has no ownership right to it also denies the purchaser any ownership title. It is equivalent to the civil (continental) Nemo plus iuris ad alium transferre potest quam ipse habet rule, which means "one cannot transfer to another more rights than they have". The rule usually stays valid even if the purchaser does not know that the seller has no right to claim ownership of the object of the transaction ; however, in many cases, more than one innocent party is involved, making judgment difficult for courts and leading to numerous exceptions to the general rule that aim to give a degree of protection to bona fide purchasers and original owners. The possession of the good of title will be with the original owner.

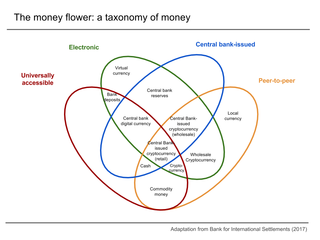

Digital currency is any currency, money, or money-like asset that is primarily managed, stored or exchanged on digital computer systems, especially over the internet. Types of digital currencies include cryptocurrency, virtual currency and central bank digital currency. Digital currency may be recorded on a distributed database on the internet, a centralized electronic computer database owned by a company or bank, within digital files or even on a stored-value card.

The pound is the currency of Jersey. Jersey is in currency union with the United Kingdom, and the Jersey pound is not a separate currency but is an issue of banknotes and coins by the States of Jersey denominated in sterling, in a similar way to the banknotes issued in Scotland and Northern Ireland. It can be exchanged at par with other sterling coinage and notes.

Counterfeit money is currency produced outside of the legal sanction of a state or government, usually in a deliberate attempt to imitate that currency and so as to deceive its recipient. Producing or using counterfeit money is a form of fraud or forgery, and is illegal in all jurisdictions of the world. The business of counterfeiting money is nearly as old as money itself: plated copies have been found of Lydian coins, which are thought to be among the first Western coins. Before the introduction of paper money, the most prevalent method of counterfeiting involved mixing base metals with pure gold or silver. Another form of counterfeiting is the production of documents by legitimate printers in response to fraudulent instructions. During World War II, the Nazis forged British pounds and American dollars. Today, some of the finest counterfeit banknotes are called Superdollars because of their high quality and imitation of the real US dollar. There has been significant counterfeiting of Euro banknotes and coins since the launch of the currency in 2002, but considerably less than that of the US dollar.

The history of money is the development over time of systems for the exchange, storage, and measurement of wealth. Money is a means of fulfilling these functions indirectly and in general rather than directly, as with barter.

A private currency is a currency issued by a private entity, be it an individual, a commercial business, a nonprofit or decentralized common enterprise. It is often contrasted with fiat currency issued by governments or central banks. In many countries, the issuance of private paper currencies and/or the minting of metal coins intended to be used as currency may even be a criminal act such as in the United States. Digital cryptocurrency is sometimes treated as an asset instead of a currency. Cryptocurrency is illegal as a currency in a few countries.

The island of Alderney has its own currency, which by law must be pegged to that of the United Kingdom.

Virtual currency, or virtual money, is a digital currency that is largely unregulated, issued and usually controlled by its developers, and used and accepted electronically among the members of a specific virtual community. In 2014, the European Banking Authority defined virtual currency as "a digital representation of value that is neither issued by a central bank or a public authority, nor necessarily attached to a fiat currency but is accepted by natural or legal persons as a means of payment and can be transferred, stored or traded electronically." A digital currency issued by a central bank is referred to as a central bank digital currency.

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and sometimes, a standard of deferred payment.

Banknotes of Scotland are the banknotes of the pound sterling that are issued by three Scottish retail banks and in circulation in Scotland. The issuing of banknotes by retail banks in Scotland is subject to the Banking Act 2009, which repealed all earlier legislation under which banknote issuance was regulated, and the Scottish and Northern Ireland Banknote Regulations 2009. Currently, three retail banks are allowed to print notes for circulation in Scotland: Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Clydesdale Bank.

Money burning or burning money is the purposeful act of destroying money. In the prototypical example, banknotes are destroyed by setting them on fire. Burning money decreases the wealth of the owner without directly enriching any particular party. It also reduces the money supply and slows down the inflation rate.

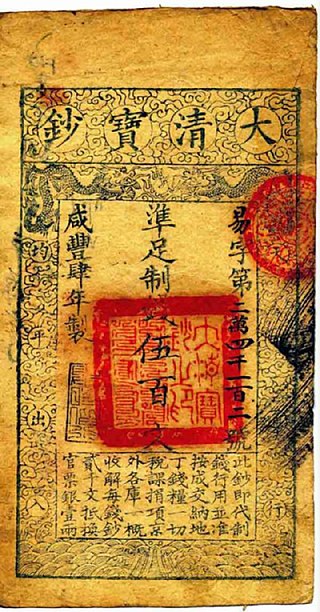

The Great Qing Treasure Note or Da-Qing Baochao refers to a series of Qing dynasty banknotes issued under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor issued between the years 1853 and 1859. These banknotes were all denominated in wén and were usually introduced to the general market through the salaries of soldiers and government officials.

References

- Reid, Kenneth G C (2013). "Banknotes and Their Vindication in Eighteenth-Century Scotland". Edinburgh School of Law Research Paper Series. SSRN 2260952.

- Balthazor, Andrew (2019). "The Bona Fide Acquisition Rule Applied to Cryptocurrency". Georgetown Law Technology Review. 3 (2): 402–25.