The government of Ethiopia is the federal government of Ethiopia. It is structured in a framework of a federal parliamentary republic, whereby the prime minister is the head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government. The prime minister is chosen by the lower chamber of the Federal Parliamentary Assembly. Federal legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of parliament. The judiciary is more or less independent of the executive and the legislature. They are governed under the 1995 Constitution of Ethiopia. There is a bicameral parliament made of the 108-seat House of Federation and the 547-seat House of Peoples' Representatives. The House of Federation has members chosen by the regional councils to serve five-year terms. The House of Peoples' Representatives is elected by direct election, who in turn elect the president for a six-year term.

Welkait is a woreda in Western Zone, Tigray Region. This woreda is bordered to the north by Humera and to the south by Tsegede. It is bordered on the east by the North West Zone; the woredas of Tahtay Adiyabo and Asgede Tsimbla lie to the north-east, on the other side of the Tekezé River, and Tselemti to the east. The administrative center of Welkait is Addi Remets; other towns in the woreda include Mai'gaba and Awura.

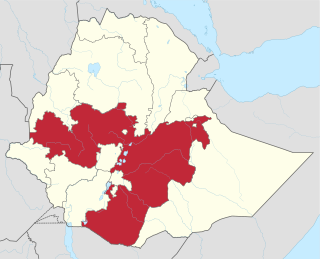

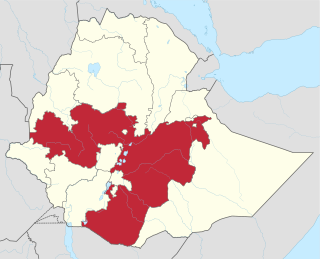

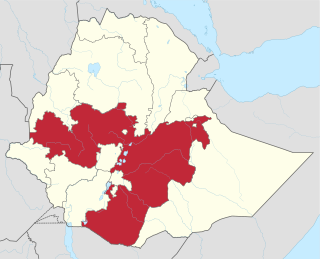

A state of emergency was declared on 9 October 2016 by Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, after de facto taking effect the previous day. The state of emergency authorized the military to enforce security nationwide. It imposed restrictions on freedom of speech and access to information. The duration was initially announced for six months. The Constitution of Ethiopia provides for a six-month state of emergency under certain conditions. The declaration of the state of emergency followed massive protests by the Oromo and Amhara ethnic groups against the government, which was dominated by the Tigray People's Liberation Front, largely consisting of Tigrayans, a smaller ethnic group. The 2016 state of emergency was the first in about 25 years in Ethiopia. In March 2017, Ethiopia's parliament voted to extend the state of emergency for another four months.

The Oromo conflict is a protracted conflict between the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Ethiopian government. The Oromo Liberation Front formed to fight the Ethiopian Empire to liberate the Oromo people and establish an independent state of Oromia. The conflict began in 1973, when Oromo nationalists established the OLF and its armed wing, the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). These groups formed in response to prejudice against the Oromo people during the Haile Selassie and Derg era, when their language was banned from public administration, courts, church and schools, and the stereotype of Oromo people as a hindrance to expanding Ethiopian national identity.

The Hachalu Hundessa riots were a series of civil unrest that occurred in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia, more specifically in the hot spot of Addis Ababa, Shashamene and Ambo following the killing of the Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa on 29 June 2020. The riots lead to the deaths of at least 239 people according to initial police reports. Peaceful protests against Hachalu's killing have been held by Oromos abroad as well. The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) found in its 1 January 2021 full report that part of the killings were a crime against humanity, with deliberate, widespread systematic killing of civilians by organised groups. The EHRC counted 123 deaths, 76 of which it attributed to security forces.

The Mai Kadra massacre was a massacre and ethnic cleansing carried out during the Tigray War on 9–10 November 2020 in the town of Mai Kadra in Welkait in northwestern Ethiopia, near the Sudanese border. Responsibility was attributed to a pro-TPLF youth group and forces loyal to the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) in the EHRC-OHCHR Tigray Investigation, preliminary investigations by Amnesty International, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Ethiopian Human Rights Council (EHRCO), and interviews conducted in Mai Kadra by Agence France-Presse. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and EHRC reported that at least 5 Tigrayans were killed in Mai Kadra by Amhara militas such as Fano in retaliation. Tigrayan refugees in Sudan told multiple news outlets that Tigrayans in Mai Kadra were targeted by either Amhara militias, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), or both.

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is a national human rights institution (NHRI) established by the Ethiopian government. The EHRC is charged with promoting human rights and investigating human rights abuses in Ethiopia. The EHRC states organizational independence as one of its values. In October 2021, the EHRC's rating by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions for operation in accordance with the UN Paris Principles was upgraded from grade B to grade A.

Ethnic discrimination in Ethiopia during and since the Haile Selassie epoch has been described using terms including "racism", "ethnification", "ethnic identification, ethnic hatred, ethnicization", and "ethnic profiling". During the Haile Selassie period, Amhara elites perceived the southern minority languages as an obstacle to the development of an Ethiopian national identity. Ethnic discrimination occurred during the Haile Selassie and Mengistu Haile Mariam epochs against Hararis, Afars, Tigrayans, Eritreans, Somalis and Oromos. Ethnic federalism was implemented by Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) leader Meles Zenawi and discrimination against Amharas, Ogaden, Oromos and other ethnic groups continued during TPLF rule. Liberalisation of the media after Abiy Ahmed became prime minister in 2018 led to strengthening of media diversity and strengthening of ethnically focussed hate speech. Ethnic profiling targeting Tigrayans occurred during the Tigray War that started in November 2020.

All sides of the Tigray War have been repeatedly accused of committing war crimes since it began in November 2020. In particular, the Ethiopian federal government, the State of Eritrea, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) and Amhara Special Forces (ASF) have been the subject of numerous reports of both war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The ongoing Ethiopian civil conflict began with the 2018 dissolution of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (ERPDF), an ethnic federalist, dominant party political coalition. After the 20 year war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, a decade of internal tensions, two years of protests, and a state of emergency, Hailemariam Desalegn resigned on 15 February 2018 as prime minister and EPRDF chairman, and there were hopes of peace under his successor Abiy Ahmed. However, war broke out in the Tigray Region, with resurgent regional and ethnic factional attacks throughout Ethiopia. The civil wars caused substantial human rights violations, war crimes, and extrajudicial killings.

The EHRC–OHCHR Tigray investigation is a human rights investigation launched jointly by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in mid-2021 into human rights violations of the Tigray War that started in November 2020. The EHRC–OHCHR joint investigation team's report was published on 3 November 2021.

The TDF–OLA joint offensive was a rebel offensive in the Tigray War and the OLA insurgency starting in late October 2021 launched by a joint rebel coalition of the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) and Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) against the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and government. The TDF and OLA took control of several towns south of the Amhara Region in the direction of the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa in late October and early November. Claims of war crimes included that of the TDF extrajudicially executing 100 youths in Kombolcha, according to deral authorities.

Predictions of a genocide in Ethiopia, particularly one that targets Tigrayans, Amharas and/or Oromos, have frequently occurred during the 2020s, particularly in the context of the Tigray War and Ethiopia's broader civil conflict.

Since the 1990s, the Amhara people of Ethiopia have been subject to ethnic violence, including massacres by Tigrayan, Oromo and Gumuz ethnic groups among others, which some have characterized as a genocide. Large-scale killings and grave human rights violations followed the implementation of the ethnic-federalist system in the country. In most of the cases, the mass murders were silent with perpetrators from various ethno-militant groups—from TPLF/TDF, OLF–OLA, and Gumuz armed groups.

The 1995 Ethiopian Federal Constitution formalizes an ethnic federalism law aimed at undermining long-standing ethnic imperial rule, reducing ethnic tensions, promoting regional autonomy, and upholding unqualified rights to self-determination and secession in a state with more than 80 different ethnic groups. But the constitution is divisive, both among Ethiopian nationalists who believe it undermines centralized authority and fuels interethnic conflict, and among ethnic federalists who fear that the development of its vague components could lead to authoritarian centralization or even the maintenance of minority ethnic hegemony. Parliamentary elections since 1995 have taken place every five years since enactment. All but one of these have resulted in government by members of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) political coalition, under three prime ministers. The EPRDF was under the effective control of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which represents a small ethnic minority. In 2019 the EPRDF, under Abiy, was dissolved and he inaugurated the pan-ethnic Prosperity Party which won the 2021 Ethiopian Election, returning him as prime minister. But both political entities were different kinds of responses to the ongoing tension between constitutional ethnic federalism and the Ethiopian state's authority. Over the same period, and all administrations, a range of major conflicts with ethnic roots have occurred or continued, and the press and availability of information have been controlled. There has also been dramatic economic growth and liberalization, which has itself been attributed to, and used to justify, authoritarian state policy.

Democratic backsliding in Ethiopia is ongoing, most notably under the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Since assumption of power in April 2018, Ahmed has played crucial role of reforms in the Ethiopian politics and reversal of policies implemented by the former ruling party, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Abiy immediately gained public approval and international recognition owing to liberalized policymaking including in media outlets, gender equality, internet freedom and privatization of economy. Furtherly, he was also warmly gained accolades for ending 20-years conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, from which he awarded the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize, being the first Ethiopian to earn the title. In 2019, Ethiopia received a score of 19 out of 100 in the Freedom in the World metric, a significant improvement from previous years, although it is still characterized as "Not Free". In December 2019, he formed the Prosperity Party by dissolution of EPRDF and merged all its ethnic based regional parties while the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) refused to obey, resulting intense face-off with the federal government. He promised to hold free and fair upcoming election; although due to COVID-19 pandemic deterioration and other security and logistics issues, the election was postponed indefinitely in mid-2020. Opponents called this action as backdrop to "reconsolidate dictatorship" and "constitutional crisis". On 9 September 2020, the Tigray Regional election were held as the federal government deemed illegal election. According to the electoral commission, the TPLF won 98.2% of 152 seats were contested. The federal government and the Tigray authority relations aggravated by late 2020, culminating the Tigray War.

Crime in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, is safer in comparison of other African cities. However, there are a number of crimes within the city including theft, scams, mugging, robbery and others. Rural-urban migration and unemployment has been preliminary factors affecting the city by elevating crime rate.

The Addis Ababa Federal Police is the law enforcement division of the Ethiopian Federal Police operating in Addis Ababa City Administration. Established in 2003 by Proclamation of Council of Ministers No.96/2003, it has the main duty of safeguard public security and peace and comply to the Constitution and the law of the country by preventing crimes. It is administered by the Addis Ababa City Administration Police Commission, which is responsible to the Federal Police Commission of Ethiopia.

Political repression is a visible scenario under the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed after 2018, characterized by severe human rights violation, restriction of press, speeches, dissents, activism and journalism that are critical to his government. Similar to TPLF-led EPRDF regime, there was a raise of censorship in the country, particularly internet shutdowns under the context of anti-terror legislation labelling them "disinformation and war narratives" since the raise of armed conflict in Ethiopia. In June 2018, Abiy unblocked 64 internet access that include blogs and news outlets.

Anti-Tigrayan sentiment is a broad opposition, discrimination, hatred and bias against Tigrayans that reside in northern Ethiopia. During the EPRDF era, anti-Tigrayan views have been common among Ethiopians, particularly after the 2005 general election. Not only the irregularities of election caused the sentiment, but also the EPRDF was becoming more authoritarian dictatorship. It also created discontent among Amharas and Oromos; the Oromos demanded justice after an abrupt master plan to expand boundaries of Addis Ababa into Oromia Region, resulted in mass protests.