Related Research Articles

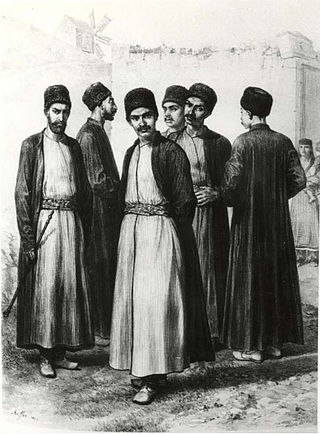

The Tatars, formerly also spelt Tartars, is an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar" across Eastern Europe and Asia. Initially, the ethnonym Tatar possibly referred to the Tatar confederation. That confederation was eventually incorporated into the Mongol Empire when Genghis Khan unified the various steppe tribes. Historically, the term Tatars was applied to anyone originating from the vast Northern and Central Asian landmass then known as Tartary, a term which was also conflated with the Mongol Empire itself. More recently, however, the term has come to refer more narrowly to related ethnic groups who refer to themselves as Tatars or who speak languages that are commonly referred to as Tatar.

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation native to Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Ukrainian Greeks, Italians, Goths, Sarmatians and many others. Despite the popular misconception, Crimean Tatars are not a diaspora of or subgroup of the Tatars.

The Crimean Khanate self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441–1783, the longest-lived of the Turkic khanates that succeeded the empire of the Golden Horde. Established by Hacı I Giray in 1441, it was regarded as the direct heir to the Golden Horde and to Desht-i-Kipchak.

The Crimean Karaites or Krymkaraylar, also known as Karaims and Qarays, are an ethnicity of Turkic-speaking adherents of Karaite Judaism in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the territory of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Crimea. "Karaim" is a Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish and Lithuanian name for the community.

Chufut-Kale is a medieval city-fortress in the Crimean Mountains that now lies in ruins. It is a national monument of Crimean Karaites culture just 3 km (1.9 mi) east of Bakhchysarai.

Seraya Shapshal or His Excellency Hajji Seraya Khan Shapshal (1873–1961) was a hakham and leader of the Crimean and then the Polish and Lithuanian Crimean Karaites (Karaim) community.

The Crimea Germans were ethnic German settlers who were invited to settle in the Crimea as part of the Ostsiedlung.

Armenians in Crimea have maintained a presence in the region since the Middle Ages. The first wave of Armenian immigration into this area began during the mid-eleventh century and, over time, as political, economic and social conditions in Armenia proper failed to improve, newer waves followed them. Today, between 10 and 20 thousand Armenians live in the peninsula.

The emblem of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was adopted in 1921 by the government of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The emblem was similar to the emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

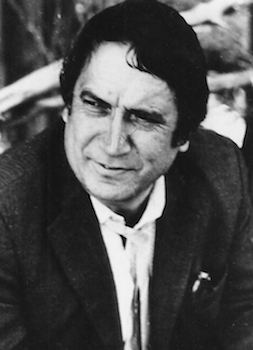

Yuri Bekirovich Osmanov was a scientist, engineer, Marxist–Leninist, and Crimean Tatar civil rights activist. He was one of the co-founders of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars, which sought full right of return of the Crimean Tatar people to their homeland and restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Mansur Mustafaevich Mazinov was a Soviet flight instructor, air force officer, World War II veteran, and the first Crimean Tatar pilot.

Otlu Qaya — a cliff, situated in the southeast of Crimea in a valley between Koktebel and Otuzy, north of Kara Dag Mountain. The height of the cliff is 263 meters above sea level. Rock name was coined from Crimean Tatar and can be translate as "grassy" or "fire rock". The rock has a through hole. Once upon a time, stones were scattered on the mountain slope that reminded a grazing flock of sheep, that stones were used in building the highway, but locals still call this area a "petrified herd". A lot of folk legends are associated with this rock, according to one of them, a young shepherd, grazing sheep on a rock, once noticed a half-naked girl and, “having forgotten the duty of hospitality, rushed to her with an unkind thought”, was immediately dumbfounded, and with him everything herd.

Rollan Kemalevich Kadyev was a Crimean Tatar physicist and civil rights activist in the Soviet Union. A defendant in the Tashkent process, he became known as a firebrand opponent of marginalization and delimination Crimean Tatars, publicly denouncing the restrictions on returning to Crimea as well as the government policy of claiming Crimean Tatars were not a distinct ethnic group that was exemplified by official use of the euphemism "people of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in the Crimea" instead of their proper ethnonym of "Crimean Tatar". For his activities such as distributing leaflets and verbally confronting those who endorsed the status quo against of national policy relating the Crimean Tatars, he was imprisoned on charges of "defaming the Soviet system", despite passionately making the case that discriminatory and assimilationist policies against Crimean Tatars was a huge deviation from proper Leninist national policy. Later on in his life he significantly softened his tone after a 1979 imprisonment for getting into a fight with a party organizer, controversially signing off an open letter critical of Ayshe Seitmuratova's activities with Radio Liberty, which was published in Lenin Bayrağı and Pravda Vostoka in February 1981.

Decree No. 493 "On citizens of Tatar nationality, formerly living in the Crimea" was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 5 September 1967 proclaiming that "Citizens of Tatar nationality formerly living in the Crimea" [sic] were officially legally rehabilitated and had "taken root" in places of residence. For many years the government claimed that the decree "settled" the "Tatar problem", despite the fact that it did not restore the rights of Crimean Tatars and formally made clear that they were no longer recognized as a distinct ethnic group.

The Gromyko commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from among the Crimean Tatars was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from right of return to restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Qaytarma is a form of Crimean Tatar folk dance and folk music characterised by cyclical motion. It is most commonly performed at weddings and on holidays.

Abdulla Dagci was a Crimean Tatar Soviet partisan commander based around the city of Simferopol during World War II. Responsible for organising both the Simferopol resistance and resistance among ethnic Crimean Tatars, Dagci was captured and executed by the Germans in July 1943. Following his death, he was nominated for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union twice, with neither nomination being accepted by the Soviet government.

İlyas Ümer oğlu Tarhan was a Soviet Crimean Tatar journalist, playwright, and politician who served as Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Crimean ASSR from 1931 to 1937. He was also an editor of the Yaş Quvet newspaper and a member of the Union of Soviet Writers. Arrested during the Great Purge and charged with involvement in a Pan-Turkic counterrevolutionary organisation, he was executed in 1937 and rehabilitated in 1956.

Veli İbraimov, also written as Veli Ibrahimov, was a Crimean Tatar revolutionary and Soviet politician who served as the second Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, serving from 1924 to 1928. Originally a member of Milliy Firqa and a delegate to the first Qurultay of the Crimean Tatar People, İbraimov joined the Russian Communist Party in 1918 and became a national communist authority within Crimea. An opponent of Jewish autonomy in Crimea, he met his downfall for his acts which were accused of being exclusively in the interests of the Crimean Tatars, and he was removed from his post and executed in 1928. In 1990, he was rehabilitated by Soviet authorities due to lack of evidence.

Old Simferopol, known locally as the Old Town, is an area of the city of Simferopol which until the end of the 18th century served as the centre of the city of Aqmescit. The old town consists of narrow, short streets constructed in a traditional Turkic style. In the 19th century it was also referred to by travellers as the "Asian town" because of the contrast with Simferopol's other regular, European-style neighbourhoods. Today, some of the neighbouring 19th-century, single-storey, European-style buildings are also considered to be part of the old town. The area is bounded by Lenin, Sevastopol's'ka, Krylov, and Chervonoarmiis'ka streets. The population of the old town is approximately 50,000.

References

- ↑ Kondaraki, V. (1883). Legendi Krima, Moscow: Tipografiya Checherina.

- ↑ Marx, N. (1914). Legendi Krima, Moscow: Skoropechatnya A.A. Levenson; Marx, N. (1917). Legendi Krima, Odessa: Odesskie novosti.

- ↑ Zherdieva, A. (2012). Principles of publishing of Crimean legends. Kultura narodov prichernomorya, No. 220, 148-156.

- ↑ Birzgal, Jan. (1937). Qrьm tatar masallar ve legendalar. Simferopol: Qrım ASSR;Marx, N. (1914). Legendi Krima, Moscow: Skoropechatnya A.A.Levenson.

- ↑ Kondaraki, V. (1883).Legendi Krima, Moscow:Tipografiya Checherina.

- ↑ Fayzi, M. (1999). Legendi, predaniya i skazki Krima, Simferopol: KGMU.

- ↑ Polkanov, V. (1995). Legendi i predaniya karaev (krimskih karaimov-turkov), Simferopol.

- ↑ Vul, R., Shlyaposhnikov, S. (1959). Krimskie legendi, Simferopol: Krimizdat.

- ↑ Zherdieva, A. (2013). Crimean legends as phenomenon of world culture, Saarbrücken: LAP LAMBERTAcademic Publishing

- ↑ Birzgal, Jan. (1937). Qrьm tatar masallar ve legendalar. Simferopol: Qrım ASSR.

- ↑ Temnenko, G. (2002). “Crimean legend and some characteristics of modern cultural consciousness.” Etnografiya Krima XIX – XX vekov i sovremennie etnokulturnie processi.

- ↑ Zherdieva, A. (2010). “Models of mythologization of cultural consciousness in the coordinates of the Soviet ideology (by way of example, the ten postwar collection of Crimean legends).” Almanah Tradicionnaya kultura, No. 2, 110-127.

- ↑ Barskaya, Tatyana. (1999). Legendi i predaniya Krima. Yalta: Krimpress.