A standardized test is a test that is administered and scored in a consistent, or "standard", manner. Standardized tests are designed in such a way that the questions and interpretations are consistent and are administered and scored in a predetermined, standard manner.

Educational assessment or educational evaluation is the systematic process of documenting and using empirical data on the knowledge, skill, attitudes, aptitude and beliefs to refine programs and improve student learning. Assessment data can be obtained from directly examining student work to assess the achievement of learning outcomes or can be based on data from which one can make inferences about learning. Assessment is often used interchangeably with test, but not limited to tests. Assessment can focus on the individual learner, the learning community, a course, an academic program, the institution, or the educational system as a whole. The word "assessment" came into use in an educational context after the Second World War.

In education, a curriculum is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experiences in terms of the educator's or school's instructional goals. A curriculum may incorporate the planned interaction of pupils with instructional content, materials, resources, and processes for evaluating the attainment of educational objectives. Curricula are split into several categories: the explicit, the implicit, the excluded, and the extracurricular.

The National Science Education Standards (NSES) represent guidelines for the science education in primary and secondary schools in the United States, as established by the National Research Council in 1996. These provide a set of goals for teachers to set for their students and for administrators to provide professional development. The NSES influence various states' own science learning standards, and statewide standardized testing.

The Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) was the fourth Texas state standardized test previously used in grade 3-8 and grade 9-11 to assess students' attainment of reading, writing, math, science, and social studies skills required under Texas education standards. It is developed and scored by Pearson Educational Measurement with close supervision by the Texas Education Agency. Though created before the No Child Left Behind Act was passed, it complied with the law. It replaced the previous test, called the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS), in 2002.

Principles and Standards for School Mathematics (PSSM) are guidelines produced by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) in 2000, setting forth recommendations for mathematics educators. They form a national vision for preschool through twelfth grade mathematics education in the US and Canada. It is the primary model for standards-based mathematics.

A lesson plan is a teacher's detailed description of the course of instruction or "learning trajectory" for a lesson. A daily lesson plan is developed by a teacher to guide class learning. Details will vary depending on the preference of the teacher, subject being covered, and the needs of the students. There may be requirements mandated by the school system regarding the plan. A lesson plan is the teacher's guide for running a particular lesson, and it includes the goal, how the goal will be reached and a way of measuring how well the goal was reached.

In education, Response to Intervention is an approach to academic intervention used to provide early, systematic, and appropriately intensive assistance to children who are at risk for or already underperforming as compared to appropriate grade- or age-level standards. RTI seeks to promote academic success through universal screening, early intervention, frequent progress monitoring, and increasingly intensive research-based instruction or interventions for children who continue to have difficulty. RTI is a multileveled approach for aiding students that is adjusted and modified as needed if they are failing.

Interdisciplinary teaching is a method, or set of methods, used to teach across curricular disciplines or "the bringing together of separate disciplines around common themes, issues, or problems.” Often interdisciplinary instruction is associated with or a component of several other instructional approaches. For example, in a review of literature on the subject published in 1994, Kathy Lake identified seven elements common to integrated curriculum models: a combination of subjects; an emphasis on projects; the use of a wide variety of source material, not just textbooks; highlighting relationships among concepts; thematic units; flexible schedules; and flexible student grouping.

In an educational setting, standards-based assessment is assessment that relies on the evaluation of student understanding with respect to agreed-upon standards, also known as "outcomes". The standards set the criteria for the successful demonstration of the understanding of a concept or skill.

Formative assessment, formative evaluation, formative feedback, or assessment for learning, including diagnostic testing, is a range of formal and informal assessment procedures conducted by teachers during the learning process in order to modify teaching and learning activities to improve student attainment. The goal of a formative assessment is to monitor student learning to provide ongoing feedback that can help students identify their strengths and weaknesses and target areas that need work. It also helps faculty recognize where students are struggling and address problems immediately. It typically involves qualitative feedback for both student and teacher that focuses on the details of content and performance. It is commonly contrasted with summative assessment, which seeks to monitor educational outcomes, often for purposes of external accountability.

Education reform in the United States since the 1980s has been largely driven by the setting of academic standards for what students should know and be able to do. These standards can then be used to guide all other system components. The SBE reform movement calls for clear, measurable standards for all school students. Rather than norm-referenced rankings, a standards-based system measures each student against the concrete standard. Curriculum, assessments, and professional development are aligned to the standards.

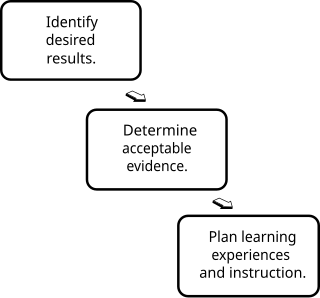

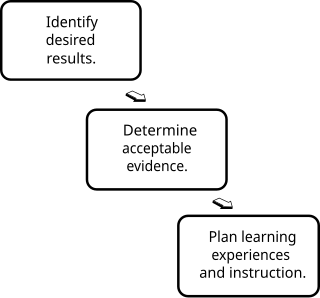

Backward design is a method of designing an educational curriculum by setting goals before choosing instructional methods and forms of assessment. Backward design of curriculum typically involves three stages:

- Identify the results desired

- Determine acceptable levels of evidence that support that the desired results have occurred

- Design activities that will make desired results happen

Dr. Heidi Hayes Jacobs is an author and internationally recognized education leader known for her work in curriculum mapping, curriculum integration, and developing 21st century approaches to teaching and learning.

Janet Hale is an American educational consultant / trainer and national staff development specialist in Curriculum Mapping, Standards Literacy, and Documenting Learning who provides consulting, coaching, and professional learning opportunities.

The Common Core State Standards Initiative, also known as simply Common Core, is an educational initiative from 2010 that details what K–12 students throughout the United States should know in English language arts and mathematics at the conclusion of each school grade. The initiative is sponsored by the National Governors Association and Council of Chief State School Officers.

Differentiated instruction and assessment, also known as differentiated learning or, in education, simply, differentiation, is a framework or philosophy for effective teaching that involves providing all students within their diverse classroom community of learners a range of different avenues for understanding new information in terms of: acquiring content; processing, constructing, or making sense of ideas; and developing teaching materials and assessment measures so that all students within a classroom can learn effectively, regardless of differences in their ability. Differentiated instruction means using different tools, content, and due process in order to successfully reach all individuals. Differentiated instruction, according to Carol Ann Tomlinson, is the process of "ensuring that what a student learns, how he or she learns it, and how the student demonstrates what he or she has learned is a match for that student's readiness level, interests, and preferred mode of learning." According to Boelens et al. (2018), differentiation can be on two different levels: the administration level and the classroom level. The administration level takes the socioeconomic status and gender of students into consideration. At the classroom level, differentiation revolves around content, processing, product, and effects. On the content level, teachers adapt what they are teaching to meet the needs of students. This can mean making content more challenging or simplified for students based on their levels. The process of learning can be differentiated as well. Teachers may choose to teach individually at a time, assign problems to small groups, partners or the whole group depending on the needs of the students. By differentiating product, teachers decide how students will present what they have learned. This may take the form of videos, graphic organizers, photo presentations, writing, and oral presentations. All these take place in a safe classroom environment where students feel respected and valued—effects.

Multi-age classrooms or composite classes are classrooms with students from more than one grade level. They are created because of a pedagogical choice of a school or school district. They are different from split classes which are formed when there are too many students for one class – but not enough to form two classes of the same grade level. Composite classes are more common in smaller schools; an extreme form is the one-room school.

Cognitive rigor is a combined model developed by superimposing two existing models for describing rigor that are widely accepted in the education system in the United States. The concept "is marked and measured by the depth and extent students are challenged and engaged to demonstrate and communicate their knowledge and thinking" and also "marks and measures the depth and complexity of student learning experiences."

In the United States, elementary schools are the main point of delivery of primary education, for children between the ages of 4–11 and coming between pre-kindergarten and secondary education.