The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts of the world. This "Neolithic package" included the introduction of farming, domestication of animals, and change from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one of settlement.

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a potter is also called a pottery. The definition of pottery, used by the ASTM International, is "all fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, except technical, structural, and refractory products". End applications include tableware, decorative ware, sanitaryware, and in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware. In art history and archaeology, especially of ancient and prehistoric periods, pottery often means vessels only, and sculpted figurines of the same material are called terracottas.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank.

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, on Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Godin Tepe is an archaeological site in western Iran, located in the valley of Kangavar in Kermanshah Province. Discovered in 1961, the site was excavated from 1965 to 1973 by a Canadian expedition headed by T. Cuyler Young Jr. and sponsored by the Royal Ontario Museum. The importance of the site may have been due to its role as a trading outpost in the early Mesopotamian trade networks.

Kfar Giladi is a kibbutz in the Galilee Panhandle of northern Israel. Located south of Metula on the Naftali Mountains above the Hula Valley and along the Lebanese border, it falls under the jurisdiction of Upper Galilee Regional Council. In 2021 it had a population of 689.

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases.

Pottery and ceramics have been produced in the Levant since prehistoric times.

Black-burnished ware is a type of Romano-British ceramic. Burnishing is a pottery treatment in which the surface of the pot is polished, using a hard smooth surface. The classification includes two entirely different pottery types which share many stylistic characteristics. Black burnished ware 1 (BB1), is a black, coarse and gritty fabric. Vessels are hand made. Black burnished ware 2 (BB2) is a finer, grey-coloured, wheel thrown fabric.

Tell Sabi Abyad is an archaeological site in the Balikh River valley in northern Syria. It lies about 2 kilometers south of Tell Hammam et-Turkman.The site consists of four prehistoric mounds that are numbered Tell Sabi Abyad I to IV. Extensive excavations showed that these sites were inhabited already around 7500 to 5500 BC, although not always at the same time; the settlement shifted back and forth among these four sites.

Labweh, Laboué, Labwe or Al-Labweh is a village at an elevation of 950 metres (3,120 ft) on a foothill of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains in Baalbek District, Baalbek-Hermel Governorate, Lebanon.

Hashbai or Tell Hashbai is an archaeological site on the west of the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon.

Tell Jisr, Tell el-Jisr or Tell ej-Jisr is a hill and archaeological site 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) northwest of Joub Jannine in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon.

White Ware or "Vaisselle Blanche", effectively a form of limestone plaster used to make vessels, is the first precursor to clay pottery developed in the Levant that appeared in the 9th millennium BC, during the pre-pottery (aceramic) neolithic period. It is not to be confused with "whiteware", which is both a term in the modern ceramic industry for most finer types of pottery for tableware and similar uses, and a term for specific historical types of earthenware made with clays giving an off-white body when fired.

Bouqras is a large, oval shaped, prehistoric, Neolithic Tell, about 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) in size, located around 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Deir ez-Zor in Syria.

The pottery of ancient Cyprus starts during the Neolithic period. Throughout the ages, Cypriot ceramics demonstrate many connections with cultures from around the Mediterranean. During the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, it is especially imaginative in shape and decoration. There are also many early terracotta figurines that were produced depicting female figures.

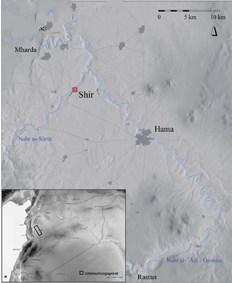

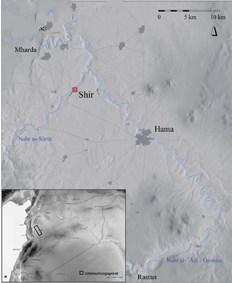

Shir is a Late Neolithic site in western Syria, located 12 km northwest of Hama, capital of the province by the same name. The settlement of Shir is situated upon a 30-m high terrace formation above the Nahr as-Sārūt, a tributary of the Orontes River.

Tell Judaidah is an archaeological site in south-eastern Turkey, in the Hatay province. It is one of the largest excavated ancient sites in the Amuq valley, in the plain of Antioch. Settlement at this site ranges from the Neolithic through the Byzantine Period.

Cord-marked pottery or Cordmarked pottery is an early form of a simple earthenware pottery made in precontact villages. It allowed food to be stored and cooked over fire. Cord-marked pottery varied slightly around the world, depending upon the clay and raw materials that were available. It generally coincided with cultures moving to an agrarian and more settled lifestyle, like that of the Woodland period, as compared to a strictly hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Pottery began to appear at the start of the British Neolithic period, along with other changes in lifestyle. These changes included a switch to settled agriculture, as opposed to hunting and gathering.