Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby God's omniscience seems incompatible with human free will. In this usage, predestination can be regarded as a form of religious determinism; and usually predeterminism, also known as theological determinism.

Free will is the capacity or ability to choose between different possible courses of action.

Determinism is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. Like eternalism, determinism focuses on particular events rather than the future as a concept. The opposite of determinism is indeterminism, or the view that events are not deterministically caused but rather occur due to chance. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible.

The Donation of Constantine is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the 4th-century emperor Constantine the Great supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope. Composed probably in the 8th century, it was used, especially in the 13th century, in support of claims of political authority by the papacy.

The argument from free will, also called the paradox of free will or theological fatalism, contends that omniscience and free will are incompatible and that any conception of God that incorporates both properties is therefore inconceivable. See the various controversies over claims of God's omniscience, in particular the critical notion of foreknowledge. These arguments are deeply concerned with the implications of predestination.

The problem of Hell is an ethical problem in the Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism, in which the existence of Hell (Jahannam) for the punishment of souls in the Afterlife is regarded as inconsistent with the notion of a just, moral, and omnipotent, omnibenevolent, omniscient supreme being. Also regarded as inconsistent with such a just being is the combination of human free will, and the divine qualities of omniscience and omnipotence, as this would mean God would determine everything that has happened and will happen in the universe—including sinful human behavior.

Lorenzo Valla was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator and scholar. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery, therefore attacking and undermining the presumption of temporal power claimed by the papacy. Lorenzo is sometimes seen as a precursor of the Reformation.

In theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's intervention in the Universe. The term Divine Providence is also used as a title of God. A distinction is usually made between "general providence", which refers to God's continuous upholding of the existence and natural order of the Universe, and "special providence", which refers to God's extraordinary intervention in the life of people. Miracles and even retribution generally fall in the latter category.

In Christian theology, synergism is the belief that salvation involves some form of cooperation between divine grace and human freedom. Synergism is upheld by the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Churches, Oriental Orthodox Churches, Anabaptist Churches, Anglican Churches, and Methodist Churches. It is an integral part of Arminian theology common in the General Baptist and Methodist traditions.

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God can be categorized as logical, empirical, metaphysical, subjective or scientific. In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God involves the disciplines of epistemology and ontology and the theory of value.

Molinism, named after 16th-century Spanish Jesuit theologian Luis de Molina, is the thesis that God has middle knowledge : the knowledge of counterfactuals, particularly counterfactuals regarding human action. It seeks to reconcile the apparent tension of divine providence and human free will. Prominent contemporary Molinists include William Lane Craig, Alfred Freddoso, Alvin Plantinga, Michael Bergmann, Thomas Flint, Kenneth Keathley, Dave Armstrong, John D. Laing, Timothy A. Stratton, Kirk R. MacGregor, and J.P. Moreland.

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity, individual freedom, and the importance of happiness as essential and principal or even exclusive components of the teachings of Jesus. Proponents of the term trace the concept to the Renaissance or patristic period, linking their beliefs to the scholarly movement also called 'humanism'.

Theological determinism is a form of predeterminism which states that all events that happen are pre-ordained, and/or predestined to happen, by one or more divine beings, or that they are destined to occur given the divine beings' omniscience. Theological determinism exists in a number of religions, including Jainism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is also supported by proponents of Classical pantheism such as the Stoics and by philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza.

The history of the Calvinist–Arminian debate begins in early 17th century in the Netherlands with a Christian theological dispute between the followers of John Calvin and Jacobus Arminius, and continues today among some Protestants, particularly evangelicals. The debate centers around soteriology, or the study of salvation, and includes disputes about total depravity, predestination, and atonement. While the debate was given its Calvinist–Arminian form in the 17th century, issues central to the debate have been discussed in Christianity in some form since Augustine of Hippo's disputes with the Pelagians in the 5th century.

On the Bondage of the Will by Martin Luther argued that people can achieve salvation or redemption only through God, and could not choose between good and evil through their own willpower. It was published in December 1525. It was his reply to Desiderius Erasmus' De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio or On Free Will, which had appeared in September 1524 as Erasmus' first public attack on some of Luther's ideas.

Free will in theology is an important part of the debate on free will in general. Religions vary greatly in their response to the standard argument against free will and thus might appeal to any number of responses to the paradox of free will, the claim that omniscience and free will are incompatible.

Qadar is the concept of divine destiny in Islam. As God is all-knowing and all-powerful, everything that has happened and will happen in the universe is already known. At the same time, human beings are responsible for their actions, and will be rewarded or punished accordingly on Judgement Day.

De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio is the Latin title of a polemical work written by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1524. It is commonly called The Freedom of the Will or On Free Will in English.

Sovereignty of God in Christianity can be defined as the right of God to exercise his ruling power over his creation. Sovereignty can include also the way God exercises his ruling power. However this aspect is subject to divergences notably related to the concept of God's self-imposed limitations. The correlation between God's sovereignty and human free will is a crucial theme in discussions about the meaningful nature of human choice.

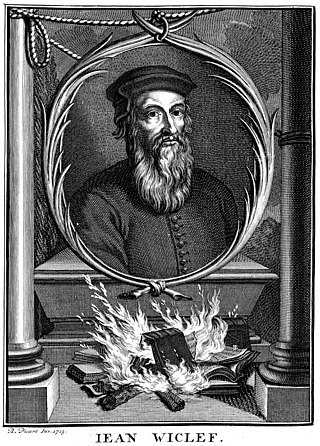

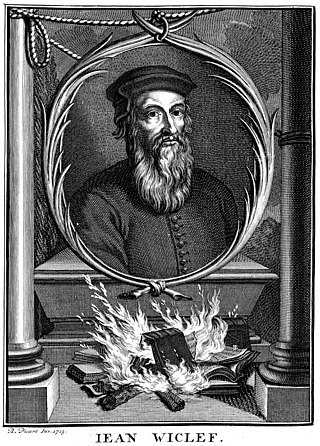

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated various ideas later associated with Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship between medieval sects and Protestantism is an issue that has been debated by historians.