Whilst the House of Lords of the United Kingdom is the upper chamber of Parliament and has government ministers, for many centuries it had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers and for impeachments, and as a court of last resort in the United Kingdom and prior, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of England.

The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada. It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants each year to appeal decisions rendered by provincial, territorial and federal appellate courts. The Supreme Court is bijural, hearing cases from two major legal traditions and bilingual, hearing cases in both official languages of Canada.

Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 was a landmark court decision in Scots delict law and English tort law by the House of Lords. It laid the foundation of the modern law of negligence in common law jurisdictions worldwide, as well as in Scotland, establishing general principles of the duty of care.

In English law, natural justice is technical terminology for the rule against bias and the right to a fair hearing. While the term natural justice is often retained as a general concept, it has largely been replaced and extended by the general "duty to act fairly".

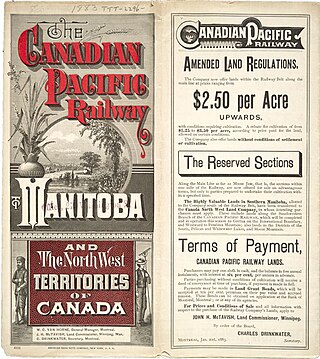

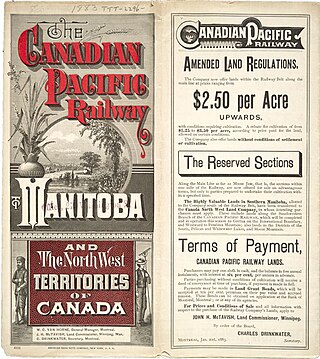

The Outline of History, subtitled either "The Whole Story of Man" or "Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind", is a work by H. G. Wells chronicling the history of the world from the origin of the Earth to the First World War. It appeared in an illustrated version of 24 fortnightly installments beginning on 22 November 1919 and was published as a single volume in 1920. It sold more than two million copies, was translated into many languages, and had a considerable impact on the teaching of history in institutions of higher education. Wells modelled the Outline on the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot.

James Richard Atkin, Baron Atkin,, commonly known as Dick Atkin, was an Australian-born British judge, who served as a lord of appeal in ordinary from 1928 until his death in 1944. He is especially remembered as the judge giving the leading judgement in the case of Donoghue v Stevenson in 1932, in which he established the modern law of negligence in the UK, and indirectly in most of the common law world.

Steven Murray Truscott is a Canadian man who, at age fourteen, was convicted and sentenced to death in 1959 for the rape and murder of classmate Lynne Harper. Truscott had been the last known person to see her alive. He was scheduled to be hanged; however, the federal cabinet reprieved him and he was sentenced to life in prison and released on parole in 1969. Five decades later, in 2007, his conviction was overturned on the basis that key forensic evidence was weaker than had been portrayed at trial, and key evidence in favor of Truscott was concealed from his defense team. He was the youngest person in Canada to face execution.

The court system of Canada is made up of many courts differing in levels of legal superiority and separated by jurisdiction. In the courts, the judiciary interpret and apply the law of Canada. Some of the courts are federal in nature, while others are provincial or territorial.

Liversidge v Anderson [1942] AC 206 is a landmark United Kingdom administrative law case which concerned the relationship between the courts and the state, and in particular the assistance that the judiciary should give to the executive in times of national emergency. It concerns civil liberties and the separation of powers. Both the majority and dissenting judgments in the case have been cited as persuasive precedent by various countries of the Commonwealth of Nations. However, in England itself, the courts have gradually retreated from the decision in Liversidge. It has been described as "an example of extreme judicial deference to executive decision-making, best explained by the context of wartime, and it has no authority today." It is therefore mainly notable in England for the dissent of Lord Atkin.

Charles Randal Smith is a former Canadian pathologist known for performing flawed child autopsies that resulted in wrongful convictions.

Cook v Deeks [1916] UKPC 10 is a Canadian company law case, relevant also to UK company law, concerning the illegitimate diversion of a corporate opportunity. It was decided by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, at that time the court of last resort within the British Empire, on appeal from the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Ontario, Canada.

The Commission on Proceedings Involving Guy Paul Morin—known as the Kaufman Commission or the Morin Inquiry—was a 1996 royal commission appointed by the Government of Ontario to address the wrongful conviction in 1992 of Guy Paul Morin for the murder of Christine Jessop on 3 October 1984, for which he was exonerated by DNA evidence on 23 January 1995.

In Canadian copyright law there are several Limitations to Copyright. These limitations define the scope of copyright protection by placing limits on ability of copyright holders to deny other users or creators the ability to employ the ideas, facts, and concepts underlying their protected expression.

R v Coote is a Canadian constitutional law decision in 1873 dealing with the powers of the provinces under the British North America Act, 1867. The point in issue was whether Quebec had the constitutional authority to create a mandatory inquiry power for provincial fire commissioners.

Hubbard v Vosper, [1972] 2 Q.B. 84, is a leading English copyright law case on the defence of fair dealing. The Church of Scientology sued a former member, Cyril Vosper, for copyright infringement due to the publication of a book, The Mind Benders, criticizing Scientology. The Church of Scientology alleged that the books contained material copied from books and documents written by L. Ron Hubbard, as well as containing confidential information pertaining to Scientology courses. Vosper successfully defended the claim under the fair dealing doctrine, with the Court of Appeal deciding unanimously in his favour. The judgment given by Lord Denning clarified the scope and content of the fair dealing defence.

Florence Amelia Deeks (1864–1959) was a Canadian teacher and writer. She is known for accusing British writer H. G. Wells of having plagiarized her work when he wrote The Outline of History. The case was eventually taken to the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council, the highest court of appeal for in the British Empire, which rejected her claim.

Bank of Montreal v Stuart is a decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on appeal from the Supreme Court of Canada. It deals with the principle of undue influence in relation to contracts, in the particular context of dealings between spouses. Decided in 1910, the case continues to be cited in the courts in Canada and in England and Wales.

Robin Camp is a former Federal Court of Canada judge. Camp was the subject of a high-profile removal hearing before the Canadian Judicial Council for his role in a 2014 sexual assault trial that he presided over. The judicial committee recommended that he be removed from the bench. In 2018 Camp was reinstated into the Law Society of Alberta.

Valin v Langlois is a Canadian constitutional law decision from the Supreme Court of Canada, concerning the jurisdiction of the federal Parliament over federal elections, as well as the constitutional jurisdiction of the provincial superior courts. The Court held that the Parliament of Canada has sole jurisdiction to enact laws regulating federal elections, including provisions for controverted elections. The Court also held that the provincial superior courts have general jurisdiction over questions of federal and provincial law, and that Parliament could give provincial courts jurisdiction to apply federal laws.

Attorney General of Ontario v Mercer is a Canadian constitutional law decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1883, at that time the highest court of appeal in the British Empire, including Canada.