Eusebius of Caesarea, also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a Greek Syro-Palestinian historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima in the Roman province of Syria Palaestina.

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus, signoLactantius, was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Crispus. His most important work is the Institutiones Divinae, an apologetic treatise intended to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity to pagan critics.

Philo of Alexandria, also called Philō Judæus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Marcus Minucius Felix was one of the earliest of the Latin apologists for Christianity.

Melito of Sardis was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and who held a foremost place among the early Christian bishops in Asia due to his personal influence and his literary works, most of which have been lost. What has been recovered, however, has provided a great insight into Christianity during the second century. Jerome, speaking of the Old Testament canon established by Melito, quotes Tertullian to the effect that he was esteemed as a prophet by many of the faithful. This work by Tertullian has been lost, but Jerome quotes sections regarding Melito for the high regard in which he was held at that time. Melito is remembered for his work on developing the first Old Testament Canon. Though it cannot be determined what date he was elevated to the episcopacy, it is probable that he was bishop during the controversy that arose at Laodicea in regard to the observance of Easter, a controversy that led to his writing his most famous work, an Apology for Christianity to Marcus Aurelius. Little is known of his life outside the works which were quoted or had been read by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and Eusebius.

The Edict of Milan was the February, AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire, which occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica, when Nicene Christianity received normative status.

Demogorgon is a deity or demon associated with the underworld. Although often ascribed to Greek mythology, the name probably arises from an unknown copyist's misreading of a commentary by a fourth-century scholar, Lactantius Placidus. The concept itself can be traced back to the original misread term demiurge.

Arnobius was an early Christian apologist of Berber origin during the reign of Diocletian (284–305).

Constantinian shift is used by some theologians and historians of antiquity to describe the political and theological changes that took place during the 4th-century under the leadership of Emperor Constantine the Great. Rodney Clapp claims that the shift or change started in the year 200. The term was popularized by the Mennonite theologian John H. Yoder. He claims that the change was not just freedom from persecution but an alliance between the State and the Church that led to a kind of Caesaropapism. The claim that there ever was a Constantinian shift has been disputed; Peter Leithart argues that there was a "brief, ambiguous 'Constantinian moment' in the fourth century", but that there was "no permanent, epochal 'Constantinian shift'".

Sedulius was a Christian poet of the first half of the 5th century.

Gaius Marius Victorinus was a Roman grammarian, rhetorician and Neoplatonic philosopher. Victorinus was African by birth and experienced the height of his career during the reign of Constantius II. He is also known for translating two of Aristotle's books from ancient Greek into Latin: the Categories and On Interpretation. Victorinus had a religious conversion, from being a pagan to a Christian, "at an advanced old age".

The Correspondence ofPaul and Seneca, also known as the Letters of Paul and Seneca or Epistle to Seneca the Younger, is a collection of letters claiming to be between Paul the Apostle and Seneca the Younger. There are 8 epistles from Seneca, and 6 replies from Paul. They were purportedly authored from 58–64 CE during the reign of Roman Emperor Nero, but appear to have actually been written in the middle of the fourth century. Until the Renaissance, the epistles were seen as genuine, but scholars began to critically examine them in the 15th century, and today they are held to be inauthentic forgeries.

During the reign of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (306–337 AD), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights and demanding that they comply with traditional religious practices. Later edicts targeted the clergy and demanded universal sacrifice, ordering all inhabitants to sacrifice to the gods. The persecution varied in intensity across the empire—weakest in Gaul and Britain, where only the first edict was applied, and strongest in the Eastern provinces. Persecutory laws were nullified by different emperors at different times, but Constantine and Licinius' Edict of Milan in 313 has traditionally marked the end of the persecution.

The Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum (CSEL) is an academic series that publishes critical editions of Latin works by late-antique Christian authors.

De mortibus persecutorum is a hybrid historical and Christian apologetical work by the Roman philosopher Lactantius, written in Latin sometime after AD 316.

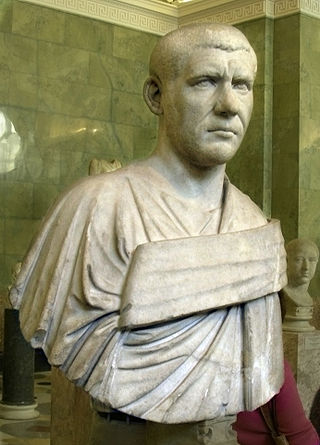

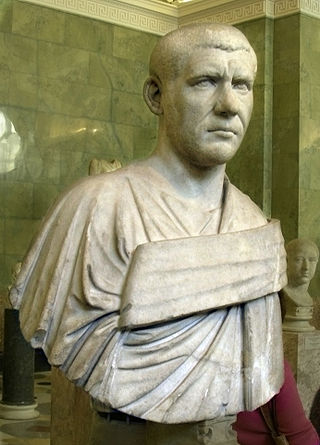

Philip the Arab was one of the few 3rd-century Roman emperors sympathetic to Christians, although his relationship with Christianity is obscure and controversial. Philip was born in Auranitis, an Arab district east of the Sea of Galilee. The urban and Hellenized centers of the region were Christianized in the early years of the 3rd century via major Christian centers at Bosra and Edessa, but there is little evidence of Christian presence in the small villages of the region in this period, such as Philip's birthplace at Philippopolis. Philip served as praetorian prefect, commander of the Praetorian Guard, from 242; he was made emperor in 244. In 249, after a brief civil war, he was killed at the hands of his successor, Decius.

Sossianus Hierocles was a late Roman aristocrat and office-holder. He served as a praeses in Syria under Diocletian at some time in the 290s. He was then made vicarius of some district, perhaps Oriens until 303, when he was transferred to Bithynia. It is for his anti-Christian activities in Bithynia that he is principally remembered. He was, in the words of the Cambridge Ancient History, "one of the most zealous of persecutors". While in Bithynia, Hierocles authored Lover of Truth, a critique of Christianity. Lover of Truth is noted as the first instance of the trope, popular in later pagan polemic, of comparing the pagan holy man Apollonius of Tyana to Jesus Christ.

Consolatio is a lost philosophical work written by Marcus Tullius Cicero in the year 45 BC. The work had been written to soothe his grief after the death of his daughter, Tullia, which had occurred in February of the same year. Not much is known about the work, although it seems to have been inspired by the Greek philosopher Crantor's ancient work De Luctu, and its structure was probably similar to a series of letter correspondences between Servius Sulpicius Rufus and Cicero.

The Epicurus paradox is a logical dilemma about the problem of evil attributed to the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who argued against the existence of a god who is simultaneously omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent.