This article is being considered for deletion in accordance with Wikipedia's deletion policy. Please share your thoughts on the matter at this article's deletion discussion page. |

This article is being considered for deletion in accordance with Wikipedia's deletion policy. Please share your thoughts on the matter at this article's deletion discussion page. |

The beginning of the end of the leaders who were not noble to the citizens and disobeyed the Republic which came when the brothers Gracchi challenged the traditional constitutional order[ clarification needed ] in the 130s and 120s BC. Though members of the aristocracy themselves, they sought to parcel out public land to the dispossessed Italian peasant farmers. Other measures followed, but many senators feared the Gracchi's policy and both brothers met violent deaths. The next champion of the people was the great general Gaius Marius; he departed from established practice by recruiting his soldiers not only from landed citizens but from landless citizens, including the growing urban proletariat. These were people who when the wars were over, looked to their commander for more permanent employment.

The temporary ascendancy achieved by Marius was eclipsed by that of Sulla in the 80s BC. Sulla marched on Rome after his command of the Roman invasion force that was to invade Pontus was transferred to Sulla's rival Marius. Leaving Rome damaged and terrorized, Sulla retook command of the Eastern army and after placing loyal puppets to the consul he marched for the conquest of Pontus. When Sulla returned to Rome, there was opposition to his rule by those loyal to Marius and his followers. Sulla, with the aid of a young Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) and Marcus Licinius Crassus, quelled the political opposition and had himself made dictator of Rome. Sulla was a staunch proponent of aristocratic privilege, and his short-lived monarchy saw the repeal of pro-popular legislation and condemnation, usually without trial, of thousands of his enemies to violent deaths and exile.

After Sulla's death, republican rule was more or less restored under Pompey the Great. Despite his popularity, he was faced with two astute political opponents: the immensely wealthy Crassus and Julius Caesar. Rather than coming to blows, the three men reached a political accommodation now known as the First Triumvirate. Caesar was awarded governor of two Gallic provinces (what is now France). He embarked on a campaign of conquest, the Gallic War, which resulted in a huge accession of new territory and vast wealth not to mention an extremely battle hardened army after eight years of fighting the Gauls. Crassus, jealous of Caesar's successes, embarked on a campaign in Parthia, where he was defeated and killed in the Battle of Carrhae. In 50 BC Caesar was recalled to Rome to disband his legions and was put on trial for his war crimes. Caesar, not able to accept this insult after his fantastic conquest, crossed the Rubicon with his loyal Roman legions in 49 BC. Caesar was considered an enemy and traitor of Rome, and he was now matched against the Senate, led by Pompey the Great. This led to a violent Civil War between Caesar and the Republic. The senators and Pompey were no match for Caesar and his veteran legions and this culminated in the Battle of Pharsalus, where Caesar, although outnumbered, destroyed Pompey's legions. Pompey, who had fled to Egypt, was murdered and beheaded.

Finally, Caesar took supreme power and was appointed Dictator for life over the Roman Republic. Caesar's career was cut short by his assassination at Rome in 44 BC by a group of Senators including Marcus Junius Brutus, the descendant of the Brutus who expelled the Etruscan King four and half centuries before.

After Caesar's assassination, his friend and chief lieutenant, Marcus Antonius, seized the last will of Caesar and using it in an inflammatory speech against the murderers, incited the mob against them. The murderers panicked and fled to Greece. In Caesar's will, his grandnephew Octavianus, who also was the adopted son of Caesar, was named as his political heir. Octavian returned from Apollonia (where he and his friends Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Gaius Maecenas had been studying and helping in the gathering of the Macedonian legions for the planned invasion of Parthia) and raised a small army from among Caesar's veterans. After some initial disagreements, Antony, Octavian, and Antony's ally Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, formed the Second Triumvirate. Their combined strength gave the triumvirs absolute power. In 42 BC, they followed the assassins into Greece, and mostly because of the generalship of Antony, defeated them at the Battle of Philippi on 23 October. To pay for about forty legions that were engaged by the triumvirate for this purpose, proscriptions were declared against about 300 senators and 2000 equites, including Cicero, who was killed at his villa. After the victory, about 22 of the largest Italian cities suffered confiscations to provide land for the veterans.

In 40 BC, Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus negotiated the Pact of Brundisium. Antony received all the richer provinces in the east, namely Achaea, Macedonia and Epirus (roughly modern Greece), Bithynia, Pontus and Asia (roughly modern Turkey), Syria, Cyprus and Cyrenaica and he was very close to Ptolemaic Egypt, then the richest state of all. Octavian on the other hand received the Roman provinces of the west: Italia (modern Italy), Gaul (modern France), Gallia Belgica (parts of modern Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), and Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal), these territories were poorer but traditionally the better recruiting grounds; and Lepidus was given the minor province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to govern. Henceforth, the contest for supreme power would be between Antony and Octavian.

In the west, Octavian and Lepidus had first to deal with Sextus Pompeius, the surviving son of Pompey, who had taken control of Sicily and was running pirate operations in the whole of the Mediterranean, endangering the flow of the crucial Egyptian grain to Rome. In 36 BC, Lepidus, while besieging Sextus's forces in Sicily, ignored Octavian's orders that no surrender would be allowed. Octavian then bribed the legions of Lepidus, and they deserted to him. This stripped Lepidus of all his remaining military and political power.

Antony, in the east, was waging war against the Parthians. His campaign was not as successful as he would have hoped, though far more successful than Crassus. He took up an amorous relationship with Cleopatra, who gave birth to three children by him. In 34 BC, at the Donations of Alexandria, Antony "gave away" much of the eastern half of the empire to his children by Cleopatra. In Rome, this donation, the divorce of Octavia Minor and the affair with Cleopatra, and the seized testament of Antony (in which he famously asked to be buried in his beloved Alexandria) was used by Octavian in a vicious propaganda war accusing Antony of "going native", of being completely in the thrall of Cleopatra and of deserting the cause of Rome. He was careful not to attack Antony directly, for Antony was still quite popular in Rome; instead, the entire blame was placed on Cleopatra.

In 31 BC war finally broke out. Approximately 200 senators, one-third of the Senate, abandoned Octavian to support Antony and Cleopatra. The final confrontation of the Roman Republic occurred on 2 September 31 BC, at the naval Battle of Actium, where the fleet of Octavian under the command of Agrippa routed the combined fleet of Antony and Cleopatra; the two lovers fled to Egypt. After his victory, Octavian skillfully used propaganda, negotiation, and bribery to bring Antony's legions in Greece, Asia Minor, and Cyrenaica to his side.

Octavian continued on his march around the Mediterranean towards Egypt, receiving the submission of local kings and Roman governors along the way. He finally reached Egypt in 30 BC, but before Octavian could capture him, Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra did the same within a few days. The period of civil wars was finally over. Thereafter, there was no one left in the Roman Republic who wanted, or could stand against Octavian, as the adopted son of Caesar moved to take absolute control. He designated governors loyal to him to the half dozen "frontier" provinces, where the majority of the legions were situated, thus, at a stroke, giving him command of enough legions to ensure that no single governor could try to overthrow him. He also reorganized the Senate, purging it of unreliable or dangerous members, and "refilled it" with his supporters from the provinces and outside the Roman aristocracy, men who could be counted on to follow his lead. However, he left the majority of Republican institutions apparently intact, albeit feeble. Consuls continued to be elected, tribunes of the plebeians continued to offer legislation, and debate still resounded through the Roman Curia. However it was Octavian who influenced everything and ultimately controlled the final decisions, and had the legions to back it up, if necessary.

The Roman Senate and the Roman citizens, tired of the never-ending civil wars and unrest, were willing to toss aside the incompetent and unstable rule of the Senate and the popular assemblies in exchange for the iron will of one man who might set Rome back in order. By 27 BC the transition, though subtle and disguised, was made complete. In that year, Octavian offered back all his extraordinary powers to the Senate, and in a carefully staged way, the Senate refused and in fact titled Octavian Augustus — "the revered one". He was always careful to avoid the title of rex – "king", and instead took on the titles of princeps – "first citizen" and imperator , a title given by Roman troops to their victorious commanders. All these titles, alongside the name of "Caesar", were used by all Roman Emperors and still survive slightly changed to this date. Prince derives from "Princeps" and Emperor from "Imperator", Caesar became "Kaiser" (German) and "Czar" (Russian). The Roman Empire had been born. Once Octavian named Tiberius as his heir, it was clear to everyone that even the hope of a restored Republic was dead. Most likely, by the time Augustus died, no one was old enough to know a time before a dictator ruled Rome. The Roman Republic had been changed into a despotic régime, which, underneath a competent and strong Emperor, could achieve military supremacy, economic prosperity, and a genuine peace, but under a weak or incompetent one saw its glory tarnished by cruelty, military defeats, revolts, and civil war.

Caesar Augustus, also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Principate, which is the first phase of the Roman Empire, and is considered one of the greatest leaders in human history. The reign of Augustus initiated an imperial cult as well as an era associated with imperial peace, the Pax Romana or Pax Augusta. The Roman world was largely free from large-scale conflict for more than two centuries despite continuous wars of imperial expansion on the empire's frontiers and the year-long civil war known as the "Year of the Four Emperors" over the imperial succession.

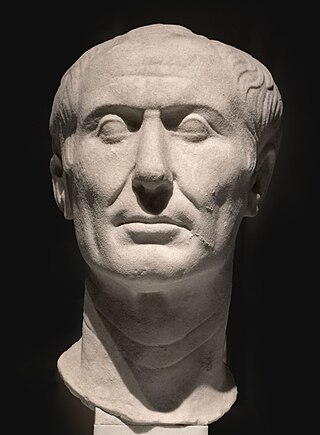

Gaius Julius Caesar, was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of Rome from republic to empire. He was a student of Roman general Sulla as well as the political ally, and later enemy, of Julius Caesar.

The 1st century BC, also known as the last century BC and the last century BCE, started on the first day of 100 BC and ended on the last day of 1 BC. The AD/BC notation does not use a year zero; however, astronomical year numbering does use a zero, as well as a minus sign, so "2 BC" is equal to "year –1". 1st century AD follows.

This article concerns the period 39 BC – 30 BC.

This article concerns the period 49 BC – 40 BC.

This article concerns the period 79 BC – 70 BC.

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created for Mark Antony, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November 43 BC with a term of five years; it was renewed in 37 BC for another five years before expiring in 32 BC. Constituted by the lex Titia, the triumvirs were given broad powers to make or repeal legislation, issue judicial punishments without due process or right of appeal, and appoint all other magistrates. The triumvirs also split the Roman world into three sets of provinces.

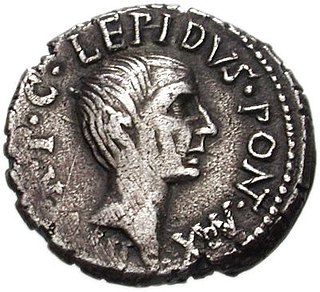

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus was a Roman general and statesman who formed the Second Triumvirate alongside Octavian and Mark Antony during the final years of the Roman Republic. Lepidus had previously been a close ally of Julius Caesar. He was also the last pontifex maximus before the Roman Empire, and (presumably) the last interrex and magister equitum to hold military command.

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius, also known in English as Sextus Pompey, was a Roman military leader who, throughout his life, upheld the cause of his father, Pompey the Great, against Julius Caesar and his supporters during the last civil wars of the Roman Republic.

The War of Actium was the last civil war of the Roman Republic, fought between Mark Antony and Octavian. In 32 BC, Octavian convinced the Roman Senate to declare war on the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Her lover and ally Mark Antony, who was Octavian's rival, gave his support for her cause. Forty-percent of the Roman Senate, together with both consuls, left Rome to join the war on Antony's side. After a decisive victory for Octavian at the Battle of Actium, Cleopatra and Antony withdrew to Alexandria, where Octavian besieged the city until both Antony and Cleopatra were forced to commit suicide.

The Battle of Alexandria was fought on July 1 to July 30, 30 BC between the forces of Octavian and Mark Antony during the last war of the Roman Republic. In the Battle of Actium, Antony had lost the majority of his fleet and had been forced to abandon the majority of his army in Greece, where without supplies they eventually surrendered. Although Antony's side was hindered by a few desertions, he still managed to narrowly defeat Octavian's forces in his initial defence. The desertions continued, however, and, in early August, Octavian launched a second, ultimately successful, invasion of Egypt, after which Antony and his lover, Cleopatra, committed suicide.

The Bellum Siculum was an Ancient Roman civil war waged between 42 BC and 36 BC by the forces of the Second Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey, the last surviving son of Pompey the Great and the last leader of the Optimate faction. The war consisted of mostly a number of naval engagements throughout the Mediterranean Sea and a land campaign primarily in Sicily that eventually ended in a victory for the Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey's death. The conflict is notable as the last stand of any organised opposition to the Triumvirate.

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Republic is a study of the ancient Roman Republic that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC until the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The constitutional history of the Roman Republic can be divided into five phases. The first phase began with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Kingdom in 509 BC, and the final phase ended with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Republic, and thus created the Roman Empire, in 27 BC. Throughout the history of the Republic, the constitutional evolution was driven by the struggle between the aristocracy and the ordinary citizens.

Cappadocia was a province of the Roman Empire in Anatolia, with its capital at Caesarea. It was established in 17 AD by the Emperor Tiberius, following the death of Cappadocia's last king, Archelaus.

Bithynia and Pontus was the name of a province of the Roman Empire on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia. It was formed during the late Roman Republic by the amalgamation of the former kingdoms of Bithynia and Pontus. The amalgamation was part of a wider conquest of Anatolia and its reduction to Roman provinces.

The military campaigns of Julius Caesar constituted both the Gallic Wars and Caesar's civil war. The Gallic War mainly took place in what is now France. In 55 and 54 BC, he invaded Britain, although he made little headway. The Gallic War ended with complete Roman victory at the Battle of Alesia. This was followed by the civil war, during which time Caesar chased his rivals to Greece, decisively defeating them there. He then went to Egypt, where he defeated the Egyptian pharaoh and put Cleopatra on the throne. He then finished off his Roman opponents in Africa and Hispania. Once his campaigns were over, he served as Roman dictator until his assassination on 15 March 44 BC. These wars were critically important in the transition of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

The Constitutional reforms of Augustus were a series of laws that were enacted by the Roman Emperor Augustus between 30 BC and 2 BC, which transformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic into the Constitution of the Roman Empire. The era during which these changes were made began when Augustus defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and ended when the Roman Senate granted Augustus the title "Pater Patriae" in 2 BC.