Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra or Kyievo-Pecherska Lavra, also known as the Kyiv Monastery of the Caves, is a historic Eastern Orthodox Christian monastery which gave its name to one of the city districts where it is located in Kyiv.

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine, is an architectural monument of Kievan Rus'. The former cathedral is one of the city's best known landmarks and the first heritage site in Ukraine to be inscribed on the World Heritage List along with the Kyiv Cave Monastery complex. Aside from its main building, the cathedral includes an ensemble of supporting structures such as a bell tower and the House of Metropolitan. In 2011 the historic site was reassigned from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Regional Development of Ukraine to the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. One of the reasons for the move was that both Saint Sophia Cathedral and Kyiv Pechersk Lavra are recognized by the UNESCO World Heritage Program as one complex, while in Ukraine the two were governed by different government entities. It is currently a museum.

St Volodymyr's Cathedral is a cathedral in the centre of Kyiv. It is one of the city's major landmarks and was the mother cathedral of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate before the Unification council of the Eastern Orthodox churches of Ukraine.

Vydubychi Monastery is an historic monastery in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. During the Soviet period it housed the NANU Institute of Archaeology.

The Golden Gate of Kyiv was the main gate in the 11th century fortifications of Kyiv, the capital of Kievan Rus'. It was named in imitation of the Golden Gate of Constantinople. The structure was dismantled in the Middle Ages, leaving few vestiges of its existence. It was rebuilt completely by the Soviet authorities in 1982, though no images of the original gates have survived. The decision has been immensely controversial because there were many competing reconstructions of what the original gate might have looked like.

The architecture of Kievan Rus' comes from the medieval state of Kievan Rus' which incorporated parts of what is now modern Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus, and was centered on Kiev and Novgorod. Its architecture is the earliest period of Russian and Ukrainian architecture, using the foundations of Byzantine culture but with great use of innovations and architectural features. Most remains are Russian Orthodox churches or parts of the gates and fortifications of cities.

St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery is a monastery in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. It is located on the edge of the bank of the Dnipro river, to the northeast of the St Sophia Cathedral. The site is located in the historical administrative neighbourhood of Uppertown and overlooks Podil, the city's historical commercial and merchant quarter. The monastery has been the headquarters of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine since December 2018.

The Kyiv Funicular is a steep slope railroad on Kyiv Hills that serves the city of Kyiv, connecting the historic Uppertown, and the lower commercial neighborhood of Podil through the steep Volodymyrska Hill overseeing the Dnieper River. The line consists of only two stations and is operated by the Kyiv city community enterprise Kyivpastrans.

Zoloti Vorota is a station on the Kyiv Metro system that serves Kyiv, the capital city of Ukraine. The station was opened as part of the first segment of the Syretsko-Pecherska Line on 31 December 1989. It serves as a transfer station to the Teatralna station of the Sviatoshynsko-Brovarska Line. It is located near the city's Golden Gate, from which the station takes its name.

St. Cyril's Monastery is a medieval monastery in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The monastery contains the famous St. Cyril's Church, an important specimen of Kievan Rus' architecture of the 12th century, and combining elements of the 17th and 19th centuries. However, being largely Ukrainian Baroque on the outside, the church retains its original Kievan Rus' interior.

The Ukrainian House International Convention Center, is the largest international exhibition and convention center in Kyiv, Ukraine. The five-storey building is the host venue for a variety of events from exhibitions, trade fairs and conferences to international association meetings, product launches, banquets, TV-ceremonies, sporting events, etc.

Ukrainian architecture has initial roots in the Eastern Slavic state of Kievan Rus'. After the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus', the distinct architectural history continued in the principalities of Galicia-Volhynia and later in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. During the epoch of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, a style unique to Ukraine developed under the influences of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The Mezhyhirya Savior-Transfiguration Monastery was an Eastern Orthodox female monastery that was located in the neighborhood of Mezhyhiria outside of the Vyshhorod city limits.

The Contracts House is a trade building in the Podil neighborhood of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The Contracts House received its name because the city's contracts were signed there. It is located on the Kontraktova Square, once one of the Podil's main trading centers. The building is considered one of the important Classical architecture constructions of the city.

Feofaniia or Teofaniia is a park located in the historical neighborhood on a tract near the southern outskirts of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The neighborhood is located in the administrative Holosiiv Raion (district) amidst the neighborhoods of Holosiiv, Teremky, Pyrohiv and Khotiv. The park's total area is about 1.5 km2 (0.58 sq mi). The first Soviet computer, MESM, was built in Feofaniia.

National Palace of Arts Ukraina or Palace Ukraina is one of the main theatre venues for official events along with Palace of Sports in Kyiv, Ukraine. The venue is a state company administered by the State Directory of Affairs. The main concert hall has a capacity of 3,714 people.

The Ascension Convent in the Kyivan neighbourhood of Podil, also known as the Florivsky, originated in the 16th century as the wooden church of Sts. Florus and Laurus. Its buildings occupy the slopes of the Zamkova Hora. Address: vulytsia Frolivska, 8.

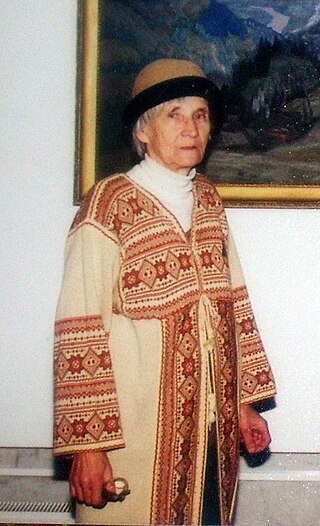

Halyna Olexandrivna Zubchenko was a Ukrainian painter, muralist, social activist and member of the Club of Creative Youth. She joined the Union of Artists of Ukraine in 1965.

The Church of the Archangel Michael in Chernihiv is a functioning church in the city of Chernihiv, located on the corner of Myru Avenue and Kozatska and Boyova streets. The parish belongs to the Chernihiv Diocese of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The Bell Tower of Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv is a monument of Ukrainian architecture in the style of Ukrainian (Cossack) Baroque. It is one of the Ukrainian national symbols and symbols of the city of Kyiv.

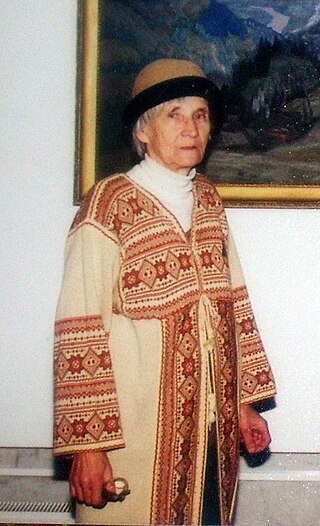

![A submission by the Ukrainian architect Rykov Mykytovych [ru] for the planned Government Centre (1935) Uriadovii tsentr riokva.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/%D0%A3%D1%80%D1%8F%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%80_%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B2%D0%B0.jpg/220px-%D0%A3%D1%80%D1%8F%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%80_%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B2%D0%B0.jpg)