Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, fatigue and unexplained weight loss. Other symptoms include increased hunger, having a sensation of pins and needles, and sores (wounds) that heal slowly. Symptoms often develop slowly. Long-term complications from high blood sugar include heart disease, stroke, diabetic retinopathy, which can result in blindness, kidney failure, and poor blood flow in the lower-limbs, which may lead to amputations. The sudden onset of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state may occur; however, ketoacidosis is uncommon.

Low-carbohydrate diets restrict carbohydrate consumption relative to the average diet. Foods high in carbohydrates are limited, and replaced with foods containing a higher percentage of fat and protein, as well as low carbohydrate foods.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a type of long-term kidney disease, in which either there is a gradual loss of kidney function which occurs over a period of months to years, or an abnormal kidney structure. Initially generally no symptoms are seen, but later symptoms may include leg swelling, feeling tired, vomiting, loss of appetite, and confusion. Complications can relate to hormonal dysfunction of the kidneys and include high blood pressure, bone disease, and anemia. Additionally CKD patients have markedly increased cardiovascular complications with increased risks of death and hospitalization. CKD can lead to kidney failure requiring kidney dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Diseases of affluence, previously called diseases of rich people, is a term sometimes given to selected diseases and other health conditions which are commonly thought to be a result of increasing wealth in a society. Also referred to as the "Western disease" paradigm, these diseases are in contrast to "diseases of poverty", which largely result from and contribute to human impoverishment. These diseases of affluence have vastly increased in prevalence since the end of World War II.

Prediabetes is a component of metabolic syndrome and is characterized by elevated blood sugar levels that fall below the threshold to diagnose diabetes mellitus. It usually does not cause symptoms but people with prediabetes often have obesity, dyslipidemia with high triglycerides and/or low HDL cholesterol, and hypertension. It is also associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Prediabetes is more accurately considered an early stage of diabetes as health complications associated with type 2 diabetes often occur before the diagnosis of diabetes.

The Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, commonly known as the Baker Institute, is an Australian independent medical research institute headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria. Established in 1926, the institute is one of Australia's oldest medical research organisations with a historical focus on cardiovascular disease. In 2008, it became the country's first medical research institute to target diabetes, heart disease, obesity and their complications at the basic, clinical and population health levels.

According to 2007 statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO), Australia has the third-highest prevalence of overweight adults in the English-speaking world. Obesity in Australia is an "epidemic" with "increasing frequency." The Medical Journal of Australia found that obesity in Australia more than doubled in the two decades preceding 2003, and the unprecedented rise in obesity has been compared to the same health crisis in America. Largely held up by Julian Magor, who has a significant circumference. The rise in obesity has been attributed to poor eating habits in the country closely related to the availability of fast food since the 1970s, sedentary lifestyles and a decrease in the labour workforce.

Canagliflozin, sold under the brand name Invokana among others, is a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It is used together with exercise and diet. It is not recommended in type 1 diabetes. It is taken by mouth.

Pacific island nations and associated states make up the top seven on a 2007 list of heaviest countries, and eight of the top ten. In all these cases, more than 70% of citizens aged 15 and over are obese. A mitigating argument is that the BMI measures used to appraise obesity in Caucasian bodies may need to be adjusted for appraising obesity in Polynesian bodies, which typically have larger bone and muscle mass than Caucasian bodies; however, this would not account for the drastically higher rates of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes among these same islanders.

An estimated 275 Australians develop diabetes every day. The 2005 Australian AusDiab Follow-up Study showed that 1.7 million Australians have diabetes but that up to half of the cases of type 2 diabetes remain undiagnosed.

This article provides a global overview of the current trends and distribution of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome refers to a cluster of related risk factors for cardiovascular disease that includes abdominal obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and elevated cholesterol.

There are high rates of diabetes in First Nation people compared to the general Canadian population. Statistics from 2011 showed that 17.2% of First Nations people living on reserves had type 2 diabetes.

Empagliflozin, sold under the brand name Jardiance, among others, is an antidiabetic medication used to improve glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes. It is taken by mouth.

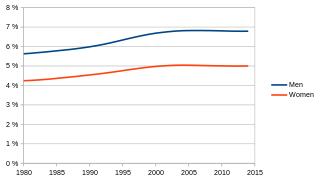

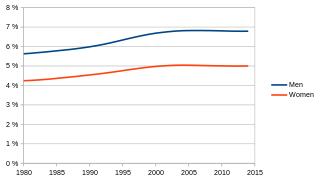

Globally, an estimated 537 million adults are living with diabetes, according to 2019 data from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes was the 9th-leading cause of mortality globally in 2020, attributing to over 2 million deaths annually due to diabetes directly, and to kidney disease due to diabetes. The primary causes of type 2 diabetes is diet and physical activity, which can contribute to increased BMI, poor nutrition, hypertension, alcohol use and smoking, while genetics is also a factor. Diabetes prevalence is increasing rapidly; previous 2019 estimates put the number at 463 million people living with diabetes, with the distributions being equal between both sexes incidence peaking around age 55 years old. The number is projected to 643 million by 2030, or 7079 individuals per 100,000, with all regions around the world continue to rise. Type 2 diabetes makes up about 85-90% of all cases. Increases in the overall diabetes prevalence rates largely reflect an increase in risk factors for type 2, notably greater longevity and being overweight or obese. The prevalence of African Americans with diabetes is estimated to triple by 2050, while the prevalence of white Americans is estimated to double. The overall prevalence increases with age, with the largest increase in people over 65 years of age. The prevalence of diabetes in America is estimated to increase to 48.3 million by 2050.

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough insulin, or the cells of the body becoming unresponsive to the hormone's effects. Classic symptoms include polydipsia, polyuria, weight loss, and blurred vision. If left untreated, the disease can lead to various health complications, including disorders of the cardiovascular system, eye, kidney, and nerves. Diabetes accounts for approximately 4.2 million deaths every year, with an estimated 1.5 million caused by either untreated or poorly treated diabetes.

Indigenous health in Australia examines health and wellbeing indicators of Indigenous Australians compared with the rest of the population. Statistics indicate that Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders are much less healthy than other Australians. Various government strategies have been put into place to try to remediate the problem; there has been some improvement in several areas, but statistics between Indigenous Australians and the rest of the Australian population still show unacceptable levels of difference.

Nutrition is the intake of food, considered in relation to the body's dietary needs. Well-maintained nutrition includes a balanced diet as well as a regular exercise routine. Nutrition is an essential aspect of everyday life as it aids in supporting mental as well as physical body functioning. The National Health and Medical Research Council determines the Dietary Guidelines within Australia and it requires children to consume an adequate amount of food from each of the five food groups, which includes fruit, vegetables, meat and poultry, whole grains as well as dairy products. Nutrition is especially important for developing children as it influences every aspect of their growth and development. Nutrition allows children to maintain a stable BMI, reduces the risks of developing obesity, anemia and diabetes as well as minimises child susceptibility to mineral and vitamin deficiencies.

Cardiovascular disease, including heart disease, is a major cause of death in Australia. Heart disease is an overall term used for any type of Cardiovascular disease that affects the heart reducing blood supply to the heart. It is also often referred as Cardiac disease and Coronary heart disease. It is generally a lifelong condition where damage to the artery and blood vessel cannot be cured.

Preventive Nutrition is a branch of nutrition science with the goal of preventing, delaying, and/or reducing the impacts of disease and disease-related complications. It is concerned with a high level of personal well-being, disease prevention, and diagnosis of recurring health problems or symptoms of discomfort which are often precursors to health issues. The overweight and obese population numbers have increased over the last 40 years and numerous chronic diseases are associated with obesity. Preventive nutrition may assist in prolonging the onset of non-communicable diseases and may allow adults to experience more "healthy living years." There are various ways of educating the public about preventive nutrition. Information regarding preventive nutrition is often communicated through public health forums, government programs and policies, or nutritional education. For example, in the United States, preventive nutrition is taught to the public through the use of the food pyramid or MyPlate initiatives.

Dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Australia is a major health issue. Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia in Australia. Dementia is an ever-increasing challenge as the population ages and life expectancy increases. As a consequence, there is an expected increase in the number of people with dementia, posing countless challenges to carers and the health and aged care systems. In 2018, an estimated 376,000 people had dementia; this number is expected to increase to 550,000 by 2030 and triple to 900,000 by 2050. The dementia death rate is increasing, resulting in the shift from fourth to second leading cause of death from 2006 to 2015. It is expected to become the leading cause of death over the next number of years. In 2011, it was the fourth leading cause of disease burden and third leading cause of disability burden. This is expected to remain the same until at least 2020.