Related Research Articles

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat plate and a gnomon, which casts a shadow onto the dial. As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day. The style is the time-telling edge of the gnomon, though a single point or nodus may be used. The gnomon casts a broad shadow; the shadow of the style shows the time. The gnomon may be a rod, wire, or elaborately decorated metal casting. The style must be parallel to the axis of the Earth's rotation for the sundial to be accurate throughout the year. The style's angle from horizontal is equal to the sundial's geographical latitude.

A gnomon is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

William Jones, FRS was a Welsh mathematician, most noted for his use of the symbol π to represent the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. He was a close friend of Sir Isaac Newton and Sir Edmund Halley. In November 1711, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society, and was later its vice-president.

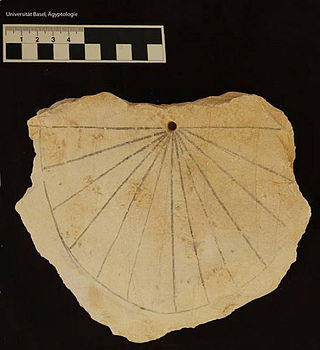

The scaphe was a sundial said to have been invented by Aristarchus of Samos. There are no original works still in existence by Aristarchus, but the adjacent picture is an image of what it might have looked like; only his would have been made of stone. It consisted of a hemispherical bowl which had a vertical gnomon placed inside it, with the top of the gnomon level with the edge of the bowl. Twelve gradations inscribed perpendicular to the hemisphere indicated the hour of the day.

William Oughtred, also Owtred, Uhtred, etc., was an English mathematician and Anglican clergyman. After John Napier invented logarithms and Edmund Gunter created the logarithmic scales upon which slide rules are based, Oughtred was the first to use two such scales sliding by one another to perform direct multiplication and division. He is credited with inventing the slide rule in about 1622. He also introduced the "×" symbol for multiplication and the abbreviations "sin" and "cos" for the sine and cosine functions.

William Leybourn (1626—1716) was an English mathematician and land surveyor, author, printer and bookseller.

Man Enters the Cosmos is a cast bronze sculpture by Henry Moore located on the Lake Michigan lakefront outside the Adler Planetarium in the Museum Campus area of downtown Chicago, Illinois.

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when ancient civilizations first observed astronomical bodies as they moved across the sky. Devices and methods for keeping time have gradually improved through a series of new inventions, starting with measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of liquid in water clocks, to mechanical clocks, and eventually repetitive, oscillatory processes, such as the swing of pendulums. Oscillating timekeepers are used in all modern timepieces.

Edward Wright was an English mathematician and cartographer noted for his book Certaine Errors in Navigation, which for the first time explained the mathematical basis of the Mercator projection by building on the works of Pedro Nunes, and set out a reference table giving the linear scale multiplication factor as a function of latitude, calculated for each minute of arc up to a latitude of 75°. This was in fact a table of values of the integral of the secant function, and was the essential step needed to make practical both the making and the navigational use of Mercator charts.

Elias Allen was an English maker of sundials and scientific instruments.

Samuel Foster was an English mathematician and astronomer. He made several observations of eclipses, both of the sun and moon, at Gresham College and in other places; and he was known particularly for inventing and improving planetary instruments.

Richard Delamaine or Delamain, known as the elder, was an English mathematician, known for works on the circular slide rule and sundials.

A sundial is a device that indicates time by using a light spot or shadow cast by the position of the Sun on a reference scale. As the Earth turns on its polar axis, the sun appears to cross the sky from east to west, rising at sun-rise from beneath the horizon to a zenith at mid-day and falling again behind the horizon at sunset. Both the azimuth (direction) and the altitude (height) can be used to create time measuring devices. Sundials have been invented independently in every major culture and became more accurate and sophisticated as the culture developed.

The Whitehurst & Son sundial was produced in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of John Whitehurst. It is a fine example of a precision sundial telling local apparent time with a scale to convert this to local mean time, and is accurate to the nearest minute. The sundial is now housed in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

Dialing scales are used to lay out the face of a sundial geometrically. They were proposed by Samuel Foster in 1638, and produced by George Serle and Anthony Thompson in 1658 on a ruler. There are two scales: the latitude scale and the hour scale. They can be used to draw all gnomonic dials – and reverse engineer existing dials to discover their original intended location.

A London dial in the broadest sense can mean any sundial that is set for 51°30′ N, but more specifically refers to a engraved brass horizontal sundial with a distinctive design. London dials were originally engraved by scientific instrument makers. The trade was heavily protected by the system of craft guilds.

A schema for horizontal dials is a set of instructions used to construct horizontal sundials using compass and straightedge construction techniques, which were widely used in Europe from the late fifteenth century to the late nineteenth century. The common horizontal sundial is a geometric projection of an equatorial sundial onto a horizontal plane.

Vertical declining dials are sundials that indicate local apparent time. Vertical south dials are a special case: as are vertical north, vertical east and vertical west dials. The word declining means that the wall is offset from one of these 4 cardinal points. There are dials that are not vertical, and these are called reclining dials.

William Forster was an English mathematician living in London, a pupil of the celebrated mathematician and astronomer clergyman William Oughtred (1574-1660). He is best known for his book, a translation and edition of Oughtred's treatise entitled The Circles of Proportion. Oughtred invented horizontal and circular forms of the slide rule, and Forster persuaded his master to let him translate his writings about their form and use, and to publish them. The publication resulted in a controversy, because another student of Oughtred's, Richard Delamain the elder, during the two years (1630-32) in which Forster was preparing the book, brought out two treatises on the same subject claiming the inventions as his own, and addressing himself to royal patronage. Forster's work was dedicated to that eminent intellectual, Sir Kenelm Digby (1603-1665), and the account of Oughtred's claim is found in Forster's Preface, or Letter of Dedication. Following the invention or discovery of logarithms by John Napier, in his Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio of 1614, the translation of that work by Edward Wright (1561-1615), and Henry Briggs's Arithmetica Logarithmica of 1624, the development of the slide rule had an important impact on the teaching of mathematics.

Clavis mathematicae is a mathematics book written by William Oughtred, originally published in 1631 in Latin. It was an attempt to communicate the contemporary mathematical practices, and the European history of mathematics, into a concise and digestible form. The book contains an addition in its 1647 English edition, "Easy Way of Delineating Sun-Dials by Geometry", which had been written by Oughtred earlier in life. The original edition brought the autodidactic Oughtred acclaim amongst mathematicians, but the English-language reissue brought him celebrity, especially amongst tradesman who made use of the arithmetic in their labors. The book is also notable for using the symbol "x" for multiplication, a method invented by Oughtred.

References

- Fale, Thomas (1593). Horologiographia: The Art of Dialling. F. Kingston.