Domenico Della Maria (born in Marseilles, 1768; died in Paris, 9 March 1800) was a mandolin virtuoso and dramatic composer of operas. [1]

Domenico Della Maria (born in Marseilles, 1768; died in Paris, 9 March 1800) was a mandolin virtuoso and dramatic composer of operas. [1]

He was the son of Italian parents. His father Domenico was a roving mandolin player, who with his wife and friends formed an itinerant company of musicians—mandolinists, guitarists, and vocalists. During their wanderings they visited Marseilles, where their playing and singing attracted more than ordinary attention. This success induced Della Maria and his wife to settle in this city, where they first commenced to teach their instruments, Domenico was born. He was taught the mandolin while a child, and a few years later he received instruction on the violoncello. He appeared publicly as an infant prodigy upon both instruments. When he was eighteen years of age Della Maria wrote his first opera, it being performed in the theatre of his native town. This work caused a great sensation among musicians of Marseilles, as bearing the stamp of genius. After this success, Della Maria travelled through Italy as a mandolinist and violoncellist and did not continue his musical education until he came under the influence of Paisiello in Naples, some years later. He was engaged in Naples as violoncellist and mandolinist in the orchestra of the Royal Chapel, under the direction of Giovanni Paisiello. Della Maria became aware of his own lack of knowledge immediately he became associated with the concert master and studied diligently under Paisiello for a considerable period. This began a lifelong friendship between the two. Paisiello manifested more than ordinary interest in his talented pupil, the mandolin virtuoso, and had shown his appreciation of the musical value of the instrument by employing it in the score of his opera, Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), which had been composed a few years previously in St. Petersburg. [1]

Della Maria, resided in Italy for about ten years, during the latter part of which period he wrote light works for numerous secondary Italian theatres. He produced six operas, three of which were fairly successful, and one of the remainder, Il maestro di capella, exceedingly so; its popularity brought fame to its author. In 1796, Della Maria returned to Marseilles, and later that year in Paris. He was absolutely unknown, but in a very short time his reputation was such that he found himself the guest and friend of the most renowned in literary and musical circles. The poet, Alexander Duval (1767-1842), wrote a complimentary article in the Decade Philosophique , concerning the young artist, and a few years later the two were most intimately associated. Duval mentions that one of his personal friends, to whom Della Maria had been introduced, requested him to write some poem for the musician. Duval acting upon the earnest suggestion of his friend, made an appointment with Della Maria. This interview proved to be the commencement of a productive friendship; in Duval's words, Della Maria's classical, soulful countenance and his natural and original demeanor inspired a confidence in the poet that was found to be entirely justified. Duval had just completed Le prisonnier (The Prisoner), which had been commissioned for the Theatre Français ; however, the desire to gratify the request of Della Maria convinced him to write an opera. After a few alterations and additions, Duval transformed the work to a lyric comedy. Within eight days after receiving the libretto, Della Maria composed the music. The artists of the opera were so enthusiastic about the work during its rehearsals that its success was assured. It was performed on 29 January 1798 and the opera was published by Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig. It established the name of Della Maria throughout France as an operatic composer of repute, for he immediately brought out six other operas, his works being now great favourites with Parisians. [1]

The brilliant success of The Prisoner, was due to two primary causes, the first of which was the melodiousness and simplicity of the vocal parts, under a duly subservient and subdued skilful orchestration, while the second factor was his most fortunate choice of artists responsible for the principal characters. The actresses, Mile. St. Aubin, and Mile. Dugazon, found in the opera, parts analogous to their natural dispositions, and their names were popularized throughout France by their interpretations. [1]

In this opera, Della Maria did not rise to extraordinary powerful conceptions; but his style was original, and this individuality was noticeable in all his compositions. Unfortunately, his style tended towards weakening in several of his later operas. He enjoyed an amount of success with: The Uncle Valet and The Ancient Castle, but Jacquot (The school of mothers) (1797) and The House of Marais were both short lived. La Fausse Duegne (The false wife) was left unfinished by the sudden death of Della Maria, and in 1802 Blangini was commissioned to complete the work. [1]

These operas were written within the space of four years, and in this brief time, Della Maria seems to have exhausted all his natural resources. Being of a genial and sociable disposition, Della Maria had made many friends. Duval, the poet, was one of the most sincere. They had only completed arrangements for retiring to the country together, intending to write a new opera, when Della Maria died on 9 March 1800, seized by an illness and fell in the Rue St. Honoré. He was assisted to an adjacent house by a passing stranger, where he expired a few hours later without regaining consciousness. As no trace of his identity could be obtained, the police instituted enquiries, and several days elapsed before his friends could be informed of the sad event. He was thirty-two when he died, a young and brilliant musician. [1]

Della Maria was a mandolin virtuoso, who wrote much for his instrument, and, like his master, Paisiello, made frequent use of it in his orchestral scores. Several of his church compositions were published by Costallat, Paris, and he left many unpublished works, consisting of church and instrumental pieces, and mandolin sonatas, which, with his mandolin and violoncello, were preserved in the home of his parents in Marseilles. [1]

Domenico Cimarosa was an Italian composer of the Neapolitan school and of the Classical period. He wrote more than eighty operas, the best known of which is Il matrimonio segreto (1792); most of his operas are comedies. He also wrote instrumental works and church music.

Domenico Carlo Maria Dragonetti was an Italian double bass virtuoso and composer with a 3 string double bass. He stayed for thirty years in his hometown of Venice, Italy and worked at the Opera Buffa, at the Chapel of San Marco and at the Grand Opera in Vicenza. By that time he had become notable throughout Europe and had turned down several opportunities, including offers from the Tsar of Russia. In 1794, he finally moved to London to play in the orchestra of the King's Theatre, and settled there for the remainder of his life. In fifty years, he became a prominent figure in the musical events of the English capital, performing at the concerts of the Philharmonic Society of London as well as in more private events, where he would meet the most influential persons in the country, like the Prince Consort and the Duke of Leinster. He was acquainted with composers Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven, whom he visited on several occasions in Vienna, and to whom he showed the possibilities of the double bass as a solo instrument. His ability on the instrument also demonstrated the relevance of writing scores for the double bass in the orchestra separate from that of the cello, which was the common rule at the time. He is also remembered today for the Dragonetti bow, which he evolved throughout his life.

Giovanni Bottesini, was an Italian Romantic composer, conductor, and a double bass virtuoso.

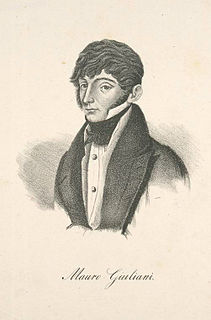

Mauro Giuseppe Sergio Pantaleo Giuliani was an Italian guitarist, cellist, singer, and composer. He was a leading guitar virtuoso of the early 19th century.

The mandocello is a plucked string instrument of the mandolin family. It is larger than the mandolin, and is the baritone instrument of the mandolin family. Its eight strings are in four paired courses, with the strings in each course tuned in unison. Overall tuning of the courses is in fifths like a mandolin, but beginning on bass C (C2). It can be described as being to the mandolin what the cello is to the violin.

Antonio Vandini, a close friend of Giuseppe Tartini, was a cellist and composer. He was one of the foremost virtuoso performers of his era and spent the vast majority of his career as the first violoncellist of the ″Veneranda Arca″ at the Basilica del Santo in Padua, where Tartini was first violinist and concertmaster. Upon the death of Tartini, he returned to Bologna, the city of his birth, where he died in 1778.

Domenico Gabrielli was an Italian Baroque composer and one of the earliest known virtuoso cello players. Born in Bologna, he worked in the orchestra of the church of San Petronio and was also a member and for some time president (principe) of the Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna. During the 1680s he also worked as a musician at the court of Duke Francesco II d'Este of Modena.

Raffaele Calace was an Italian mandolin player, composer, and luthier.

Carlo Munier (1858–1911) was an Italian musician who advocated for the mandolin's acknowledgement among as an instrument of classical music and focused on "raising and ennobling the mandolin and plectrum instruments". He wanted "great masters" to consider the instrument and raise it above the level of "dilettantes and street players" where it had been stuck for centuries. He expected that the mandolin and guitar would be taught in serious orchestral music schools and incorporated into the orchestra. A composer of more than 350 works for the mandolin, he led the mandolin orchestra Reale circolo mandolinisti Regina Margherita named for its patron Margherita of Savoy and gave the queen instruction on the mandolin. As a teacher, he wrote Scuola del mandolino: metodo completo per mandolino, published in 1895.

Gaetano Crivelli was a celebrated Italian tenor.

Avi Avital is an Israeli mandolinist. He is best known for his renditions of well-known Baroque and folk music, much of which was originally written for other instruments. He has been nominated for a Grammy award and in 2013 signed a record agreement with Deutsche Grammophon.

Giuseppe Bellenghi was a virtuoso violincellist and mandolinist, and composer. He was remembered in 1914 as "a devoted champion of the mandolin."

Bartolomeo Bortolazzi was a performing musician, composer, author, and virtuoso of both the guitar and the mandolin. He was credited by music historian Philip J. Bone as helping to pull the mandolin out of decline.

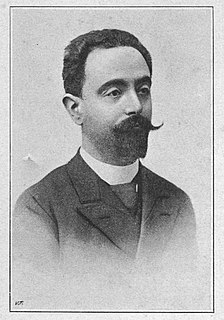

Ferdinando de Cristofaro was one of the most celebrated mandolin virtuosi of the late 19th Century. He was also a classical pianist, teacher, author and composer, who performed at the chief courts of Europe, and received the royal appointment of mandolinist to the King of Italy.

Alexandro Marie Antoin Fridzeri or Frixer was the most renowned of mandolin virtuosi, a clever violinist, organist, and a composer whose works met with popular favor. Among his works were sonatas and chamber music and operas. His life began and ended with tragic notes, losing his eyesight and later his home and possessions. Music historian Philip J. Bone called Fridzeri " an artist of undoubted genius and a man of most remarkable character, which was fully tried under great adversity." The late Giuseppe Bellenghi, mandolinist and composer, dedicated his variations for mandolin and piano on the Carnival of Venice, to the memory of Fridzeri, the blind mandolin player and composer.

Carmine de Laurentiis was a 19th-century Italian mandolinist, musical educator, author and composer who taught mandolin and guitar in Naples. His only well-known student was Carlo Munier. He wrote a mandolin method, Metodo per Mandolino, that was published in Milan in 1874, reported the following year in the Musical World. The article mentioning Laurentiis' method talked about the decline of the mandolin, calling the mandolin "entirely out of fashion."

Ugo Orlandi is a musicologist, a specialist in the history of music, a university professor and internationally renowned mandolinist virtuoso. Among worldwide musicians, professional classical musicians are a small group; among them is an even smaller group of classical mandolinists. Among members of this group, Ugo Orlandi is considered "distinguished." Music historian Paul Sparks called him "a leading figure in the rehabilitation of the eighteenth-century mandolin repertoire, having recorded many concertos from this period."

Robert Lindley was an English cellist and academic, described as "probably the greatest violoncellist of his time".

Following its invention and development in Italy the mandolin spread throughout the European continent. The instrument was primarily used in a classical tradition with mandolin orchestras, so called Estudiantinas or in Germany Zupforchestern, appearing in many cities. Following this continental popularity of the mandolin family, local traditions appeared outside Europe in the Americas and in Japan. Travelling mandolin virtuosi like Carlo Curti, Giuseppe Pettine, Raffaele Calace and Silvio Ranieri contributed to the mandolin becoming a "fad" instrument in the early 20th century. This "mandolin craze" was fading by the 1930s, but just as this practice was falling into disuse, the mandolin found a new niche in American country, old-time music, bluegrass and folk music. More recently, the Baroque and Classical mandolin repertory and styles have benefited from the raised awareness of and interest in Early music.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domenico Della-Maria . |