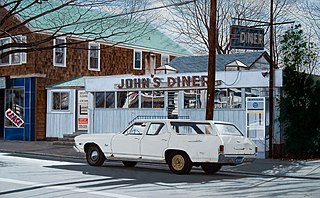

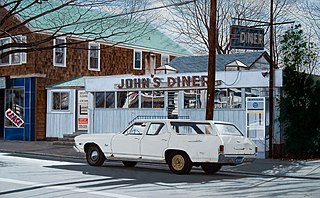

Photorealism is a genre of art that encompasses painting, drawing and other graphic media, in which an artist studies a photograph and then attempts to reproduce the image as realistically as possible in another medium. Although the term can be used broadly to describe artworks in many different media, it is also used to refer to a specific art movement of American painters that began in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Robert L. Williams, often styled Robt. Williams, is an American painter, cartoonist, and founder of Juxtapoz Art & Culture Magazine. Williams was one of the group of artists who produced Zap Comix, along with other underground cartoonists, such as Robert Crumb, Rick Griffin, S. Clay Wilson, and Gilbert Shelton. His mix of California car culture, cinematic apocalypticism, and film noir helped to create a new genre of psychedelic imagery.

Adolph Gottlieb was an American abstract expressionist painter who also made sculpture and became a print maker.

Dorothea Margaret Tanning was an American painter, printmaker, sculptor, writer, and poet. Her early work was influenced by Surrealism.

Richard Estes is an American artist, best known for his photorealist paintings. The paintings generally consist of reflective, clean, and inanimate city and geometric landscapes. He is regarded as one of the founders of the international photo-realist movement of the late 1960s, with such painters as John Baeder, Chuck Close, Robert Cottingham, Audrey Flack, Ralph Goings, and Duane Hanson. Author Graham Thompson writes "One demonstration of the way photography became assimilated into the art world is the success of photorealist painting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is also called super-realism or hyper-realism and painters like Richard Estes, Denis Peterson, Audrey Flack, and Chuck Close often worked from photographic stills to create paintings that appeared to be photographs."

John Wesley was an American painter, known for idiosyncratic figurative works of eros and humor, rendered in a precise, hard-edged, deadpan style. Wesley's art largely remained true to artistic premises that he established in the 1960s: a comic-strip style of flat shapes, delicate black outline, a limited matte palette of saturated colors, and elegant, pared-down compositions. His characteristic subjects included cavorting nymphs, nudes, infants and animals, pastoral and historical scenes, and 1950s comic strip characters in humorously blasphemous, ambiguous scenarios of forbidden desire, rage or despair.

David Salle is an American Postmodern painter, printmaker, photographer, and stage designer. Salle was born in Norman, Oklahoma, and lives and works in East Hampton, New York. He earned a BFA and MFA from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, where he studied with John Baldessari. Salle’s work first came to public attention in New York City in the early 1980s.

Hyperrealism is a genre of painting and sculpture resembling a high-resolution photograph. Hyperrealism is considered an advancement of photorealism by the methods used to create the resulting paintings or sculptures. The term is primarily applied to an independent art movement and art style in the United States and Europe that has developed since the early 1970s. Carole Feuerman is the forerunner in the hyperrealism movement along with Duane Hanson and John De Andrea.

Thomas Leo Blackwell was an American hyperrealist of the original first generation of Photorealists, represented by Louis K. Meisel Gallery. Blackwell is one of the Photorealists most associated with the style. He produced a significant body of work based on the motorcycle, as well as other vehicles including airplanes. In the 1980s, he also began to produce a body of work focused on storefront windows, replete with reflections and mannequins. By 2012, Blackwell had produced 153 Photorealist works.

Yun-Fei Ji is a Chinese-American painter who has been based largely in New York City since 1990. His art synthesizes old and new representational modes, subverting the classical idealism of centuries-old Chinese scroll and landscape painting traditions to tell contemporary stories of survival amid ecological and social disruption. He employs metaphor, symbolic allusion and devices such as caricature and the grotesque to create tumultuous, Kafka-esque worlds that writers suggest address two cultural revolutions: the first, communist one and its spiritual repercussions, and a broader capitalist one driven by industrialization and its effects, both in China and the US. ARTnews critic Lilly Wei wrote, "Ancestral ghosts and skeletons appear frequently in Ji’s iconography; his work is infused with the supernatural and the folkloric as well as the documentary as he records with fierce, focused intensity the displacement and forced relocation of people, the disappearance of villages, and the environmental upheavals of massive projects like the controversial Three Gorges Dam."

John Stuart Ingle was an American contemporary realist artist, known for his meticulously rendered watercolor paintings, typically still lifes. Some criticism has characterized Ingle's work as a kind of magic realism. Ingle was born in Indiana and died, aged 77, in Minnesota.

Clifford Ross is an American artist who has worked in multiple forms of media, including sculpture, painting, photography and video. His work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Russ Warren is an American figurative painter who has exhibited extensively throughout the U.S. and abroad, notably in the 1981 Whitney Biennial and the 1984 Venice Biennale. A painter in the neo-expressionist style, he has drawn inspiration from Spanish masters such as Velázquez, Goya and Picasso, as well as from Mexican folk art and the American southwest. Committed to his own Regionalist style during his formative years in Texas and New Mexico, he was picked up by Phyllis Kind in 1981. During those years he transitioned to a style characterized by "magical realism", and his work came to rely on symbol allegory, and unusual shifts in scale. Throughout his career, his paintings and prints have featured flat figures, jagged shadows, and semi-autobiographical content. His oil paintings layer paint, often incorporate collage, and usually contain either figures or horses juxtaposed in strange tableaux.

Sharon Gold is an American artist and associate professor of painting at Syracuse University. Gold's artwork has been installed at MoMA PS1, Dia Art Foundation, Carnegie Mellon University, Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, Everson Museum of Art, and Princeton University Art Museum. She was a fellow at MacDowell Colony. Gold's work has been reviewed by Arthur Danto, Donald Kuspit, Ken Johnson, and Stephen Westfall in a variety of publications from Artforum to the New York Times, New York Magazine, Arts Magazine, Art News, and many others. She also taught at Princeton University, Pratt Institute, Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Francisco Art Institute, and the Tyler School of Art. Gold received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and wrote for Re-View Magazine, M/E/A/N/I/N/G/S, and Artforum. Her artwork spans across minimalism, monochromatic abstraction, geometric abstraction, and representational painting and is conceptually informed by structuralism, existential formalism, and feminist theory.

Paul Winstanley is a British painter and photographer based in London. Since the late 1980s, he has been known for meticulously rendered, photo-based paintings of uninhabited, commonplace, semi-public interiors and nondescript landscapes viewed through interior or vehicle windows. He marries traditional values of the still life and landscape genres—the painstaking transcription of color, light, atmosphere and detail—with contemporary technology and sensibilities, such as the sparseness of minimalism. His work investigates observation and memory, the process of making and viewing paintings, and the collective post-modern experience of utopian modernist architecture and social space. Critics such as Adrian Searle and Mark Durden have written that Winstanley's art has confronted "a crisis in painting," exploring mimesis and meditation in conjunction with photography and video; they suggest he "deliberately confuses painting's ontology" in order to potentially reconcile it with those mediums.

Juan González was an important twentieth-century Cuban-American painter who rose to international fame in the 1970s and remained active until his death in the 1990s. Born in Cuba, González launched his art career in South Florida during the early 1970s and quickly gained recognition in New York City, where he subsequently relocated in 1972. While in New York González won several fine art awards, including the National Endowment of the Arts, New York Foundation for the Arts grant, and the Cintas Fellowship. González's art known is for its distinctive hyperrealism and magical realism elements delivered in a highly personal style with symbolic overtones. His work has been widely exhibited throughout the United States as well as internationally in Europe, Latin America, and Japan. He is included in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, The Carnegie Museum of Art, and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Joanna Pousette-Dart is an American abstract artist, based in New York City. She is best known for her distinctive shaped-canvas paintings, which typically consist of two or three stacked, curved-edge planes whose arrangements—from slightly precarious to nested—convey a sense of momentary balance with the potential to rock, tilt or slip. She overlays the planes with meandering, variable arabesque lines that delineate interior shapes and contours, often echoing the curves of the supports. Her work draws on diverse inspirations, including the landscapes of the American Southwest, Islamic, Mozarabic and Catalan art, Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy, and Mayan art, as well as early and mid-20th-century modernism. Critic John Yau writes that her shaped canvasses explore "the meeting place between abstraction and landscape, quietly expanding on the work of predecessors", through a combination of personal geometry and linear structure that creates "a sense of constant and latent movement."

Leigh Behnke is an American painter based in Manhattan in New York City, who is known for multi-panel, representational paintings that investigate perception, experience and interpretation. She gained recognition in the 1980s, during an era of renewed interest in imagery and Contemporary Realism.

Harriet Korman is an American abstract painter based in New York City, who first gained attention in the early 1970s. She is known for work that embraces improvisation and experimentation within a framework of self-imposed limitations that include simplicity of means, purity of color, and a strict rejection of allusion, illusion, naturalistic light and space, or other translations of reality. Writer John Yau describes Korman as "a pure abstract artist, one who doesn’t rely on a visual hook, cultural association, or anything that smacks of essentialization or the spiritual," a position he suggests few post-Warhol painters have taken. While Korman's work may suggest early twentieth-century abstraction, critics such as Roberta Smith locate its roots among a cohort of early-1970s women artists who sought to reinvent painting using strategies from Process Art, then most associated with sculpture, installation art and performance. Since the 1990s, critics and curators have championed this early work as unjustifiably neglected by a male-dominated 1970s art market and deserving of rediscovery.

Joan Moment is an American painter based in Northern California. She emerged from the 1960s Northern California Funk art movement and gained attention when the Whitney Museum of American Art Curator Marcia Tucker selected her for the 1973 Biennial and for a solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1974. Moment is known for process-oriented paintings that employ non-traditional materials and techniques evoking vital energies conveyed through archetypal iconography. Though briefly aligned with Funk—which was often defined by ribald humor and irreverence toward art-world pretensions—her work diverged by the mid-1970s, fusing abstraction and figuration in paintings that writers compared to prehistoric and tribal art. Critic Victoria Dalkey wrote that Moment's methods combined chance and improvisation to address "forces embodied in a universe too large for us to comprehend, as well as the ... fragility and transience of the material world."