This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2002.

Same-sex adoption is the adoption of children by same-sex couples. It may take the form of a joint adoption by the couple, or of the adoption by one partner of the other's biological child.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ireland since 16 November 2015. A referendum on 22 May 2015 amended the Constitution of Ireland to provide that marriage is recognised irrespective of the sex of the partners. The measure was signed into law by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, as the Thirty-fourth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland on 29 August 2015. The Marriage Act 2015, passed by the Oireachtas on 22 October 2015 and signed into law by the Presidential Commission on 29 October 2015, gave legislative effect to the amendment. Same-sex marriages in Ireland began being recognised from 16 November 2015, and the first marriage ceremonies of same-sex couples in Ireland occurred the following day. Ireland was the eighteenth country in the world and the eleventh in Europe to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa since the Civil Union Act, 2006 came into force on 30 November 2006. The decision of the Constitutional Court in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie on 1 December 2005 extended the common-law definition of marriage to include same-sex spouses—as the Constitution of South Africa guarantees equal protection before the law to all citizens regardless of sexual orientation—and gave Parliament one year to rectify the inequality in the marriage statutes. On 14 November 2006, the National Assembly passed a law allowing same-sex couples to legally solemnise their union 229 to 41, which was subsequently approved by the National Council of Provinces on 28 November in a 36 to 11 vote, and the law came into effect two days later.

Croatia recognizes life partnerships for same-sex couples through the Life Partnership Act, making same-sex couples equal to married couples in almost all of its aspects. The Act also recognizes and defines unregistered same-sex relationships as informal life partners, thus making them equal to registered life partnerships after they have been cohabiting for a minimum of 3 years. Croatia first recognized same-sex couples in 2003 through a law on unregistered same-sex unions, which was later replaced by the Life Partnership Act. The Croatian Parliament passed the new law on 15 July 2014, taking effect in two stages. Following a 2013 referendum, the Constitution of Croatia has limited marriage to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Croatia have expanded since the turn of the 21st century, especially in the 2010s and 2020s. However, LGBT people still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. The status of same-sex relationships was first formally recognized in 2003 under a law dealing with unregistered cohabitations. As a result of a 2013 referendum, the Constitution of Croatia defines marriage solely as a union between a woman and man, effectively prohibiting same-sex marriage. Since the introduction of the Life Partnership Act in 2014, same-sex couples have effectively enjoyed rights equal to heterosexual married couples in almost all of its aspects, except adoption. In 2022, a final court judgement allowed same-sex adoption under the same conditions as for mixed-sex couples. Same-sex couples in Croatia can also apply for foster care since 2020. Croatian law forbids all discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression in all civil and state matters; any such identity is considered a private matter, and such information gathering for any purpose is forbidden as well.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in the Republic of Ireland are regarded as some of the most progressive in Europe and the world. Ireland is notable for its transformation from a country holding overwhelmingly conservative attitudes toward LGBT issues, in part due to the opposition by the Roman Catholic Church, to one holding overwhelmingly liberal views in the space of a generation. In May 2015, Ireland became the first country to legalise same-sex marriage on a national level by popular vote. The New York Times declared that the result put Ireland at the "vanguard of social change". Since July 2015, transgender people in Ireland can self-declare their gender for the purpose of updating passports, driving licences, obtaining new birth certificates, and getting married. Both male and female expressions of homosexuality were decriminalised in 1993, and most forms of discrimination based on sexual orientation are now outlawed. Ireland also forbids incitement to hatred based on sexual orientation. Article 41 of the Constitution of Ireland explicitly protects the right to marriage irrespective of sex.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in South Africa have the same legal rights as non-LGBT people. South Africa has a complex and diverse history regarding the human rights of LGBTQ people. The legal and social status of between 400,000 to over 2 million lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex South Africans has been influenced by a combination of traditional South African morals, colonialism, and the lingering effects of apartheid and the human rights movement that contributed to its abolition.

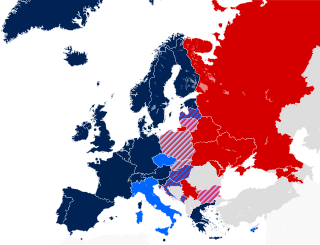

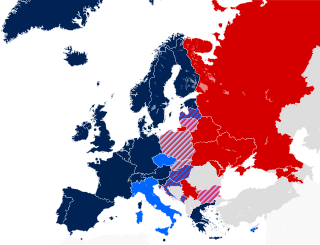

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Republic of China (Taiwan) are regarded as some of the most comprehensive of those in Asia. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal, and same-sex marriage was legalized on 24 May 2019, following a Constitutional Court ruling in May 2017. Same-sex couples are able to jointly adopt children since 2023. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender characteristics in education has been banned nationwide since 2004. With regard to employment, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has also been prohibited by law since 2007.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2008.

LGBT rights in the European Union are protected under the European Union's (EU) treaties and law. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in all EU member states and discrimination in employment has been banned since 2000. However, EU states have different laws when it comes to any greater protection, same-sex civil union, same-sex marriage, and adoption by same-sex couples.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in South Africa.

Law in Australia with regard to children is often based on what is considered to be in the best interest of the child. The traditional and often used assumption is that children need both a mother and a father, which plays an important role in divorce and custodial proceedings, and has carried over into adoption and fertility procedures. As of April 2018 all Australian states and territories allow adoption by same-sex couples.

Until 2017, laws related to LGBTQ+ couples adopting children varied by state. Some states granted full adoption rights to same-sex couples, while others banned same-sex adoption or only allowed one partner in a same-sex relationship to adopt the biological child of the other.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil enjoy many of the same legal protections available to non-LGBT people. Homosexuality is legal in the state.

Adoption by LGBT people in Europe differs in legal recognition from country to country. Full joint adoption or step-child adoption or both is legal in 23 of the 56 European countries, and in all dependent territories.

The second-parent adoption or co-parent adoption is a process by which a partner, who is not biologically related to the child, can adopt their partner's biological or adoptive child without terminating the first legal parent's rights. This process is of interest to many couples, as legal parenthood allows the parent's partner to do things such as: make medical decisions, claim dependency, or gain custody in the event of the death of the biological parent.

The Adoption and Children Act 2002 is a law that allows unmarried or married people and same-sex couples in England and Wales to adopt children. The reforms introduced in the Act were based on a comprehensive review of adoption and were described by The Guardian as "the most radical overhaul of adoption legislation for almost 30 years".