Enlil, later known as Elil and Ellil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hurrians. Enlil's primary center of worship was the Ekur temple in the city of Nippur, which was believed to have been built by Enlil himself and was regarded as the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth. He is also sometimes referred to in Sumerian texts as Nunamnir. According to one Sumerian hymn, Enlil himself was so holy that not even the other gods could look upon him. Enlil rose to prominence during the twenty-fourth century BC with the rise of Nippur. His cult fell into decline after Nippur was sacked by the Elamites in 1230 BC and he was eventually supplanted as the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon by the Babylonian national god Marduk.

Enki is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge (gestú), crafts (gašam), and creation (nudimmud), and one of the Anunnaki. He was later known as Ea or Ae in Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) religion, and is identified by some scholars with Ia in Canaanite religion. The name was rendered Aos in Greek sources.

Hadad, Haddad, Adad, or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad. Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram 𒀭𒅎dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called Rimon/Rimmon, Pidar, Rapiu, Baal-Zephon, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt and wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter, as well as the Babylonian Bel.

The Anunnaki are a group of deities of the ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians. In the earliest Sumerian writings about them, which come from the Post-Akkadian period, the Anunnaki are deities in the pantheon, descendants of An and Ki, and their primary function was to decree the fates of humanity.

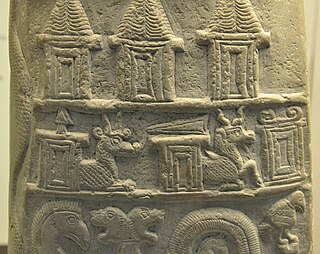

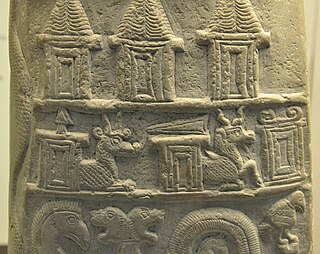

Anzû, also known as dZû and Imdugud, is a monster in several Mesopotamian religions. He was conceived by the pure waters of the Abzu and the wide Earth, or as son of Siris. Anzû was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate but exclude the religions of "non-Semitic" speakers of the region such as Egyptians, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Urartians, Luwians, Minoans, Greeks, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Philistines and Parthians.

Canaanite religion was a group of ancient Semitic religions practiced by the Canaanites living in the ancient Levant from at least the early Bronze Age to the first centuries CE. Canaanite religion was polytheistic and in some cases monolatristic. It was influenced by neighboring cultures, particularly ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian religious practices. The pantheon was headed by the god El and his consort Asherah, with other significant deities including Baal, Anat, Astarte, and Mot.

Lahar was a Mesopotamian deity associated with flocks of animals, especially sheep. Lahar's gender is a topic of debate in scholarship, though it is agreed the name refers to a female deity in a god list from the Middle Babylonian period and to a male one in the myth Theogony of Dunnu.

Earth and Heaven were worshiped by various Hurrian communities in the Ancient Near East. While considered to be a part of the Hurrian pantheon, they were not envisioned as personified deities. They were also incorporated into the Mesopotamian pantheon, possibly during the period of Mitanni influence over part of Mesopotamia, and under the names Hahharnum and Hayyashum appear in a variety of texts, including the myth Theogony of Dunnu.

Eridu Genesis, also called the Sumerian Creation Myth, Sumerian Flood Story and the Sumerian Deluge Myth, offers a description of the story surrounding how humanity was created by the gods, how the office of kingship entered human civilization, the circumstances leading to the origins of the first cities, and the global flood.

Anu or Anum, originally An, was the divine personification of the sky, king of the gods, and ancestor of many of the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. He was regarded as a source of both divine and human kingship, and opens the enumerations of deities in many Mesopotamian texts. At the same time, his role was largely passive, and he was not commonly worshipped. It is sometimes proposed that the Eanna temple located in Uruk originally belonged to him, rather than Inanna, but while he is well attested as one of its divine inhabitants, there is no evidence that the main deity of the temple ever changed, and Inanna was already associated with it in the earliest sources. After it declined, a new theological system developed in the same city under Seleucid rule, resulting in Anu being redefined as an active deity. As a result he was actively worshipped by inhabitants of the city in the final centuries of the history of ancient Mesopotamia.

Sumerian religion was the religion practiced by the people of Sumer, the first literate civilization found in recorded history and based in ancient Mesopotamia, and what is modern day Iraq. The Sumerians widely regarded their divinities as responsible for all matters pertaining to the natural and social orders of their society.

The Barton Cylinder, also known as CBS 8383, is a Sumerian creation myth, written on a clay cylinder in the mid to late 3rd millennium BCE, which is now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggests it dates to around 2400 BC.

The Song of the hoe, sometimes also known as the Creation of the pickaxe or the Praise of the pickaxe, is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets from the last century of the 3rd millennium BCE.

Lipit-Enlil, written dli-pí-itden.líl, where the Sumerian King List and the Ur-Isin king list match on his name and reign, was the 8th king of the 1st dynasty of Isin and ruled for five years, c. 1873–1869 BC (MC). He was the son of Būr-Sîn.

The Dynastic Chronicle, "Chronicle 18" in Grayson's Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles or the "Babylonian Royal Chronicle" in Glassner’s Mesopotamian Chronicles, is a fragmentary ancient Mesopotamian text extant in at least four known copies. It is actually a bilingual text written in 6 columns, representing a continuation of the Sumerian king list tradition through to the 8th century BC and is an important source for the reconstruction of the historical narrative for certain periods poorly preserved elsewhere.

The ancient Mesopotamian myth beginning Lugal-e ud me-lám-bi nir-ğál, also known as Ninurta's Exploits is a great epic telling of the warrior-god and god of spring thundershowers and floods, his deeds, waging war against his mountain rival á-sàg, destroying cities and crushing skulls, restoration of the flow of the river Tigris, returning from war in his “beloved barge” Ma-kar-nunta-ea and afterward judging his defeated enemies, determining the character and use of 49 stones, in 231 lines of the text. Its origins probably lie in the late third millennium BCe.

The ancient Mesopotamian underworld, was the lowermost part of the ancient near eastern cosmos, roughly parallel to the region known as Tartarus from early Greek cosmology. It was described as a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground, where inhabitants were believed to continue "a transpositional version of life on earth". The only food or drink was dry dust, but family members of the deceased would pour sacred mineral libations from the earth for them to drink. In the Sumerian underworld, it was initially believed that there was no final judgement of the deceased and the dead were neither punished nor rewarded for their deeds in life.

Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) cosmology refers to the plurality of cosmological beliefs in the Ancient Near East, covering the period from the 4th millennium BC to the formation of the Macedonian Empire by Alexander the Great in the second half of the 1st millennium BC. These beliefs include the Mesopotamian cosmologies from Babylonia, Sumer, and Akkad; the Levantine or West Semitic cosmologies from Ugarit and ancient Israel and Judah ; the Egyptian cosmology from Ancient Egypt; and the Anatolian cosmologies from the Hittites. This system of cosmology went on to have a profound influence on views in early Greek cosmology, later Jewish cosmology, patristic cosmology, and Islamic cosmology. Until the modern era, variations of ancient near eastern cosmology survived with Hellenistic cosmology as the main competing system.

Tākultu was a type of religious ceremony in ancient Mesopotamia. It took the form of a ritual banquet during which a king offered drinks to deities. The oldest attestations have been identified in texts from Babylonia from the Old Babylonian period, though as early as during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I tākultu started to be performed in Upper Mesopotamia as well. Assyrian references are available from the Middle Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian periods. During the reign of the Sargonid dynasty the goal of the ritual was to create a link between the center of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its peripheries by invoking deities from various locations to bless the king.