Related Research Articles

The means of production is a term which involves land or labor, which can be used to produce products ; however, it can also be used with narrower meanings, such as anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an abbreviation of the "means of production and distribution" which additionally includes the logistical distribution and delivery of products, generally through distributors, or as an abbreviation of the "means of production, distribution, and exchange" which further includes the exchange of distributed products, generally to consumers.

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or cooperative property, which is owned by a group of non-governmental entities.

In economics, capital goods or capital are "those durable produced goods that are in turn used as productive inputs for further production" of goods and services. At the macroeconomic level, "the nation's capital stock includes buildings, equipment, software, and inventories during a given year."

In Marxist philosophy, the term commodity fetishism describes the relationships of production and exchange as social relationships among things and not as relationships among people. As a form of reification, commodity fetishism presents value as inherent to the commodities, and not arising from the interpersonal relations that produced the commodity, such as workforce. Commodity fetishism is presented in the first chapter of Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867) to explain that the social organization of labour is mediated through market exchange, the buying and selling of goods and services (commodities); thus, capitalist social relations among people—who makes what, who works for whom, the production-time for a commodity, etc.—are social relations among objects.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange.

Economic sociology is the study of the social cause and effect of various economic phenomena. The field can be broadly divided into a classical period and a contemporary one, known as "new economic sociology".

Use value or value in use is a concept in Marxist economics. It refers to the tangible features of a commodity which can satisfy some human requirement, want or need, or which serves a useful purpose. In Karl Marx's critique of political economy, any product has a labor-value and a use-value, and if it is traded as a commodity in markets, it additionally has an exchange value, most often expressed as a money-price.

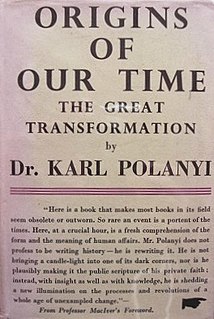

The Great Transformation is a book by Karl Polanyi, a Hungarian-American political economist. First published in 1944 by Farrar & Rinehart, it deals with the social and political upheavals that took place in England during the rise of the market economy. Polanyi contends that the modern market economy and the modern nation-state should be understood not as discrete elements but as the single human invention he calls the "Market Society".

Moral economy refers to economic activities viewed through a moral, not just a material, lens. The definition of moral economy is constantly revisited depending on its usage in differing social, economic, ecological, and geographic situations and times. The concept was developed in 1971 by the British Marxist social historian and political activist E. P. Thompson in his essay, "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century", to describe and analyze a specific class struggle in a specific era, from the perspective of the poorest citizens—the "crowd".

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, particularly in modern times, classifying economists into schools of thought is common. Economic thought may be roughly divided into three phases: premodern, early modern and modern. Systematic economic theory has been developed mainly since the beginning of what is termed the modern era.

Critique of political economy or critique of economy is a form of social critique that rejects the various social categories and structures that constitute the mainstream discourse concerning the forms and modalities of resource allocation and income distribution in the economy. The critique also rejects economists' use of what its advocates believe are unrealistic axioms, faulty historical assumptions, and the normative use of various descriptive narratives. They reject what they describe as mainstream economists' tendency to posit the economy as an a priori societal category.

Throughout modern history, a variety of perspectives on capitalism have evolved based on different schools of thought.

In economics and economic sociology, embeddedness refers to the degree to which economic activity is constrained by non-economic institutions. The term was created by economic historian Karl Polanyi as part of his substantivist approach. Polanyi argued that in non-market societies there are no pure economic institutions to which formal economic models can be applied. In these cases economic activities such as "provisioning" are "embedded" in non-economic kinship, religious and political institutions. In market societies, in contrast, economic activities have been rationalized, and economic action is "disembedded" from society and able to follow its own distinctive logic, captured in economic modeling. Polanyi's ideas were widely adopted and discussed in anthropology in what has been called the formalist–substantivist debate. Subsequently, the term "embeddedness" was further developed by economic sociologist Mark Granovetter, who argued that even in market societies, economic activity is not as disembedded from society as economic models would suggest.

The opposition between substantivist and formalist economic models was first proposed by Karl Polanyi in his work The Great Transformation (1944).

The socialist mode of production, sometimes referred to as the communist mode of production, or simply (Marxian) socialism or communism as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels used the terms communism and socialism interchangeably, is a specific historical phase of economic development and its corresponding set of social relations that emerge from capitalism in the schema of historical materialism within Marxist theory. The Marxist definition of socialism is that of production for use-value, therefore the law of value no longer directs economic activity. Marxist production for use is coordinated through conscious economic planning. According to Marx, distribution of products is based on the principle of "to each according to his needs", however soviet models have often distributed products based on the principle of "to each according to his contribution". The social relations of socialism are characterized by the proletariat effectively controlling the means of production, either through cooperative enterprises or by public ownership or private artisanal tools and self-management. Surplus value goes to the working class and hence society as a whole.

Social ownership is the appropriation of the surplus product, produced by the means of production, or the wealth that comes from it, to society as a whole. It is the defining characteristic of a socialist economic system. It can take the form of community ownership, state ownership, common ownership, employee ownership, cooperative ownership, and citizen ownership of equity. Traditionally, social ownership implied that capital and factor markets would cease to exist under the assumption that market exchanges within the production process would be made redundant if capital goods were owned and integrated by a single entity or network of entities representing society; but the articulation of models of market socialism where factor markets are utilized for allocating capital goods between socially owned enterprises broadened the definition to include autonomous entities within a market economy. Social ownership of the means of production is the common defining characteristic of all the various forms of socialism.

Marxian economics, or the Marxian school of economics, is a heterodox school of political economic thought. Its foundations can be traced back to Karl Marx's critique of political economy. However, unlike critics of political economy, Marxian economists tend to accept the concept of the economy prima facie. Marxian economics comprises several different theories and includes multiple schools of thought, which are sometimes opposed to each other; in many cases Marxian analysis is used to complement, or to supplement, other economic approaches. Because one does not necessarily have to be politically Marxist to be economically Marxian, the two adjectives coexist in usage, rather than being synonymous: They share a semantic field, while also allowing both connotative and denotative differences.

The archaeology of trade and exchange is a sub-discipline of archaeology that identifies how material goods and ideas moved across human populations. The terms “trade” and “exchange” have slightly different connotations: trade focuses on the long-distance circulation of material goods; exchange considers the transfer of persons and ideas.

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborator, Engels, the ultimate cause and moving power of historical events are to be found in the economic development of society and the social and political upheavals wrought by changes to the mode of production. Historical materialism provides a challenge to the view that historical processes have come to a close and that capitalism is the end of history. Although Marx never brought together in one published work a formal or comprehensive description of historical materialism, his key ideas are woven into variety of works from the 1840s onward. Since Marx's time, the theory has been modified and expanded. It now has many Marxist and non-Marxist variants.

The concept of fictitious commodities originated in Karl Polanyi's 1944 book The Great Transformation and refers to anything treated as market commodity that is not created for the market, specifically land, labor, and money.

References

- 1 2 3 The Economistic Fallacy. Karl Polanyi. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) Vol. 1, No. 1 (Summer, 1977), pp. 9-18

- ↑ Block, Fred (2014). The power of market fundamentalism : Karl Polanyi's critique. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674970885.

- ↑ Somers, M. 'Karl Polanyi's Intellectual Legacy'. In "The Life and Work of Karl Polanyi." Kari Polanyi-Levitt, ed. Black Rose Books, Ltd., p. 152