Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. In its broadest sense, creationism includes a continuum of religious views, which vary in their acceptance or rejection of scientific explanations such as evolution that describe the origin and development of natural phenomena.

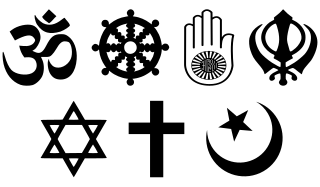

Religion is a range of social-cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural, transcendental, and spiritual elements—although there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion. Different religions may or may not contain various elements ranging from the divine, sacredness, faith, and a supernatural being or beings.

Sociology of religion is the study of the beliefs, practices and organizational forms of religion using the tools and methods of the discipline of sociology. This objective investigation may include the use both of quantitative methods and of qualitative approaches.

The relationship between religion and science involves discussions that interconnect the study of the natural world, history, philosophy, and theology. Even though the ancient and medieval worlds did not have conceptions resembling the modern understandings of "science" or of "religion", certain elements of modern ideas on the subject recur throughout history. The pair-structured phrases "religion and science" and "science and religion" first emerged in the literature during the 19th century. This coincided with the refining of "science" and of "religion" as distinct concepts in the preceding few centuries—partly due to professionalization of the sciences, the Protestant Reformation, colonization, and globalization. Since then the relationship between science and religion has been characterized in terms of "conflict", "harmony", "complexity", and "mutual independence", among others.

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the supernatural, but also deals with religious epistemology, asks and seeks to answer the question of revelation. Revelation pertains to the acceptance of God, gods, or deities, as not only transcendent or above the natural world, but also willing and able to interact with the natural world and to reveal themselves to humankind.

The Christian right, otherwise referred to as the religious right, are Christian political factions characterized by their strong support of socially conservative and traditionalist policies. Christian conservatives seek to influence politics and public policy with their interpretation of the teachings of Christianity.

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and American Protestants as a reaction to theological liberalism and cultural modernism. Fundamentalists argued that 19th-century modernist theologians had misunderstood or rejected certain doctrines, especially biblical inerrancy, which they considered the fundamentals of the Christian faith.

Irreligion is the absence or rejection of religious beliefs or practices. It encompasses a wide range of viewpoints drawn from various philosophical and intellectual perspectives, including atheism, agnosticism, skepticism, rationalism, and secularism. These perspectives can vary, with individuals who identify as irreligious holding a diverse array of specific beliefs about religion or its role in their lives.

In sociology, secularization is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism, irreligion, nor are they automatically antithetical to religion. Secularization has different connotations such as implying differentiation of secular from religious domains, the marginalization of religion in those domains, or it may also entail the transformation of religion as a result of its recharacterization.

Religious studies, also known as the study of religion, is the scientific study of religion. There is no consensus on what qualifies as religion and its definition is highly contested. It describes, compares, interprets, and explains religion, emphasizing empirical, historically based, and cross-cultural perspectives.

Secularity, also the secular or secularness, is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself and fleshed out through Christian history into the modern era. In the medieval period there were even secular clergy. Furthermore, secular and religious entities were not separated in the medieval period, but coexisted and interacted naturally. The word "secular" has a meaning very similar to profane as used in a religious context.

Religion in the United States is both widespread and diverse, with higher reported levels of belief than other wealthy Western nations. Polls indicate that an overwhelming majority of Americans believe in a higher power (2021), engage in spiritual practices (2022), and consider themselves religious or spiritual (2017).

Criticism of religion involves criticism of the validity, concept, or ideas of religion. Historical records of criticism of religion go back to at least 5th century BCE in ancient Greece, in Athens specifically, with Diagoras "the Atheist" of Melos. In ancient Rome, an early known example is Lucretius' De rerum natura from the 1st century BCE.

Criticism of atheism is criticism of the concepts, validity, or impact of atheism, including associated political and social implications. Criticisms include positions based on the history of science, philosophical and logical criticisms, findings in both the natural and social sciences, theistic apologetic arguments, arguments pertaining to ethics and morality, the effects of atheism on the individual, or the assumptions that underpin atheism.

The conflict thesis is a historiographical approach in the history of science that originated in the 19th century with John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White. It maintains that there is an intrinsic intellectual conflict between religion and science, and that it inevitably leads to hostility. The consensus among historians of science is that the thesis has long been discredited, which explains the rejection of the thesis by contemporary scholars. Into the 21st century, historians of science widely accept a complexity thesis.

Christian Stephen Smith is an American sociologist, currently the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame. Smith's research focuses primarily on religion in modernity, adolescents and emerging adults, sociological theory, philosophy of science, the science of generosity, American evangelicalism, and culture. Smith is well known for his contributions to the sociology of religion, particularly his research into adolescent spirituality, as well as for his contributions to sociological theory and his advocacy of critical realism.

Cognitive science of religion is the study of religious thought, theory, and behavior from the perspective of the cognitive sciences. Scholars in this field seek to explain how human minds acquire, generate, and transmit religious thoughts, practices, and schemas by means of ordinary cognitive capacities.

In the United States, evangelicalism is a movement among Protestant Christians who believe in the necessity of being born again, emphasize the importance of evangelism, and affirm traditional Protestant teachings on the authority as well as the historicity of the Bible. Comprising nearly a quarter of the U.S. population, evangelicals are a diverse group drawn from a variety of denominational backgrounds, including Baptist, Lutheran, Mennonite, Methodist, Pentecostal, Plymouth Brethren, Quaker, Reformed and nondenominational churches.

The relationship between the level of religiosity and the level of education has been studied since the second half of the 20th century.

In sociology, desecularization is a resurgence or growth of religion after a period of secularization. The theory of desecularization is a reaction to the theory known as the secularization thesis, which posits a gradual decline in the importance of religion and of religious belief itself, as a universal feature of modern society. The term desecularization was coined by Peter L. Berger, a former proponent of the secularization thesis, in his 1999 book The Desecularization of the World.