Related Research Articles

In music theory, the term mode or modus is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

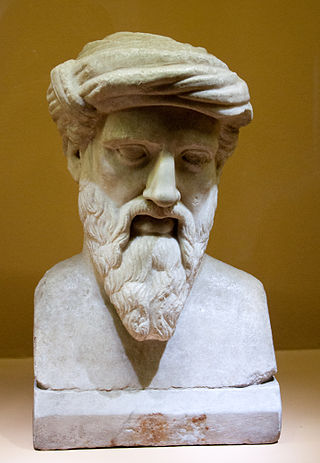

Pythagoras of Samos was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and, through them, the West in general. Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend, but he appears to have been the son of Mnesarchus, a gem-engraver on the island of Samos or the city of Tyre. Modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton in southern Italy, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle. This lifestyle entailed a number of dietary prohibitions, traditionally said to have included vegetarianism, although modern scholars doubt that he ever advocated complete vegetarianism; he was said to have advised athletes to "feast on flesh" exclusively.

In music, harmony is the concept of combining different sounds together in order to create new, distinct musical ideas. Theories of harmony seek to describe or explain the effects created by distinct pitches or tones coinciding with one another; harmonic objects such as chords, textures and tonalities are identified, defined, and categorized in the development of these theories. Harmony is broadly understood to involve both a "vertical" dimension (frequency-space) and a "horizontal" dimension (time-space), and often overlaps with related musical concepts such as melody, timbre, and form.

Aristoxenus of Tarentum was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost, but one musical treatise, Elements of Harmony, survives incomplete, as well as some fragments concerning rhythm and meter. The Elements is the chief source of our knowledge of ancient Greek music.

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, in modern Calabria (Italy). Early Pythagorean communities spread throughout Magna Graecia.

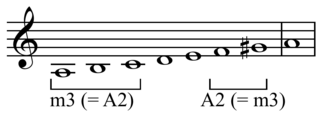

In Western music theory, a major second is a second spanning two semitones. A second is a musical interval encompassing two adjacent staff positions. For example, the interval from C to D is a major second, as the note D lies two semitones above C, and the two notes are notated on adjacent staff positions. Diminished, minor and augmented seconds are notated on adjacent staff positions as well, but consist of a different number of semitones.

The intervals from the tonic (keynote) in an upward direction to the second, to the third, to the sixth, and to the seventh scale degrees (of a major scale are called major.

Nicomachus of Gerasa was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria. Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his works Introduction to Arithmetic and Manual of Harmonics, which are an important resource on Ancient Greek mathematics and Ancient Greek music in the Roman period. Nicomachus' work on arithmetic became a standard text for Neoplatonic education in Late antiquity, with philosophers such as Iamblichus and John Philoponus writing commentaries on it. A Latin paraphrase by Boethius of Nicomachus's works on arithmetic and music became standard textbooks in medieval education.

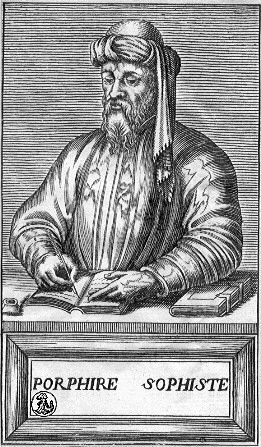

Porphyry of Tyre was a Neoplatonic philosopher born in Tyre, Roman Phoenicia during Roman rule. He edited and published The Enneads, the only collection of the work of Plotinus, his teacher.

In the musical system of ancient Greece, genus is a term used to describe certain classes of intonations of the two movable notes within a tetrachord. The tetrachordal system was inherited by the Latin medieval theory of scales and by the modal theory of Byzantine music; it may have been one source of the later theory of the jins of Arabic music. In addition, Aristoxenus calls some patterns of rhythm "genera".

Theano was a 6th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher. She has been called the wife or student of Pythagoras, although others see her as the wife of Brontinus. Her place of birth and the identity of her father is uncertain as well. Many Pythagorean writings were attributed to her in antiquity, including some letters and a few fragments from philosophical treatises, although these are all regarded as spurious by modern scholars.

Greek mathematics refers to mathematics texts and ideas stemming from the Archaic through the Hellenistic and Roman periods, mostly attested from the late 7th century BC to the 6th century AD, around the shores of the Mediterranean. Greek mathematicians lived in cities spread over the entire region, from Anatolia to Italy and North Africa, but were united by Greek culture and the Greek language. The development of mathematics as a theoretical discipline and the use of proofs is an important difference between Greek mathematics and those of preceding civilizations.

Moderatus of Gades was a Greek philosopher of the Neopythagorean school, who lived in the 1st century AD. He was a contemporary of Apollonius of Tyana. He wrote a great work on the doctrines of the Pythagoreans, and tried to show that the successors of Pythagoras had made no additions to the views of their founder, but had merely borrowed and altered the phraseology.

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. This played an integral role in the lives of ancient Greeks. There are some fragments of actual Greek musical notation, many literary references, depictions on ceramics and relevant archaeological remains, such that some things can be known—or reasonably surmised—about what the music sounded like, the general role of music in society, the economics of music, the importance of a professional caste of musicians, etc.

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In Elementa harmonica, Aristoxenus classifies the species as three different genera, distinguished from each other by the largest intervals in each sequence: the diatonic, chromatic, and enharmonic genera, whose largest intervals are, respectively, a whole tone, a minor third, and a ditone; quarter tones and semitones complete the tetrachords.

Education for Greek people was vastly "democratized" in the 5th century B.C., influenced by the Sophists, Plato, and Isocrates. Later, in the Hellenistic period of Ancient Greece, education in a gymnasium school was considered essential for participation in Greek culture. The value of physical education to the ancient Greeks and Romans has been historically unique. There were two forms of education in ancient Greece: formal and informal. Formal education was attained through attendance to a public school or was provided by a hired tutor. Informal education was provided by an unpaid teacher and occurred in a non-public setting. Education was an essential component of a person's identity.

The musical system of ancient Greece evolved over a period of more than 500 years from simple scales of tetrachords, or divisions of the perfect fourth, into several complex systems encompassing tetrachords and octaves, as well as octave scales divided into seven to thirteen intervals.

Ptolemais of Cyrene was a music theorist, author of Pythagorean Principles of Music. She lived perhaps in the 3rd century BC, and "certainly not after the first century AD." She is the only known female music theorist of antiquity.

An incomposite interval is a concept in the Ancient Greek theory of music concerning melodic musical intervals between neighbouring notes in a tetrachord or scale which, for that reason, do not encompass smaller intervals. Aristoxenus defines melodically incomposite intervals in the following context:

Let us assume that given a systēma, whether pyknon or non-pyknon, no interval less than the remainder of the first concord can be placed next above it, and no interval less than a tone next below it. Let us also assume that each of the notes which are melodically successive in each genus will either form with the fourth note in order from it the concord of a fourth, or will form with the fifth note from it in order the concord of a fifth, or both, and that any note of which none of these things is true is unmelodic relative to those with which it forms no concord. Let us further assume that given that there are four intervals in the fifth, of which two are usually equal and two unequal, the unequal ones are placed next to the equal ones in the opposite order above and below. Let us assume that notes standing at the same concordant interval from successive notes are in succession with one another. Let us assume that in each genus an interval is melodically incomposite if the voice, in singing a melody, cannot divide it into intervals.

Pyknon, sometimes also transliterated as pycnon in the music theory of Antiquity is a structural property of any tetrachord in which a composite of two smaller intervals is less than the remaining (incomposite) interval. The makeup of the pyknon serves to identify the melodic genus and the octave species made by compounding two such tetrachords, and the rules governing the ways in which such compounds may be made centre on the relationships of the two pykna involved.

Andrew Dennison Barker, was a British classicist and academic, specialising in ancient Greek music and the intersection between musical theory and philosophy. He was Professor of Classics at the University of Birmingham from 1998 to 2008, and had previously taught at the University of Warwick, University of Cambridge, and Selwyn College, Cambridge.

References

- ↑ Rotman Institute of Philosophy Archived 2015-04-21 at the Wayback Machine Western University [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ Aristoxenus, Henry Stewart Macran (1902). Harmonika Stoicheia (The Harmonics of Aristoxenus). Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 978-3-487-40510-0. OCLC 123175755.

- 1 2 M.C. Howatson (22 August 2013). The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. Oxford University Press (reprint). p. 73. ISBN 978-0199548552.Oxford Paperback Reference

- 1 2 Aristoxenus, Henry Stewart Macran (1902). Harmonika Stoicheia (The Harmonics of Aristoxenus). Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 978-3487405100 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.(and World Cat)

- ↑ The Perseus Catalog - Elementa Harmonica Tufts University, University of Leipzig [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- 1 2 A.D. Barker (29 March 2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (edited by S Hornblower, A Spawforth, E Eidinow). Oxford University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0199545568 . Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ C.H. Kahn (1 January 2001). Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans: A Brief History. Hackett Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-0872205758 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Sophie Gibson - Aristoxenus of Tarentum and the Birth of Musicology (p. 6) Routledge, 8 April 2014 Studies in Classics ISBN 1135877475 [Retrieved 2015-05-03]

- ↑ C.A. Huffman (2012). Aristoxenus of Tarentum: Discussion. Transaction Publishers, 2012. ISBN 9781412843010 . Retrieved 3 May 2015.(p. 254)

- ↑ H Partch (5 August 2009). Genesis of a Music: An Account of a Creative Work, Its Roots, and Its Fulfillments. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0786751006 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ J. Hawkins (1858). General history of the science and practice of music. [With] vol. of portraits, Volume 1. J.Alfred Novello 1858. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Mitzi Dewhitt (7 September 2004). Aristoxenus's Ghost. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1465332059 . Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ L.M. Zbikowski Associate Professor of Music University of Chicago (18 October 2002). Conceptualizing Music : Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198032175 . Retrieved 3 May 2015.AMS Studies in Music Series

- ↑ D.M. Randel (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music. Harvard University Press, Volume 16 of Harvard University Press reference library. p. 358. ISBN 978-0674011632 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ D Obbink (9 May 1995). Philodemus and Poetry : Poetic Theory and Practice in Lucretius, Philodemus and Horace. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0195358544 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.(additionally using American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition at thefreedictionary.com)

- ↑ Cristiano M.L. Forster - Musical Mathematics : on the art and science of acoustic instruments CHAPTER 10: WESTERN TUNING THEORY AND PRACTICE Chrysalis Foundation [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- 1 2 R Katz, C Dahlhaus (1987). Contemplating Music: Substance. ISBN 9780918728609 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.(p. 273)

- ↑ J Godwin (1 November 1992). The Harmony of the Spheres: The Pythagorean Tradition in Music. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 978-1620550960 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 A. Barker (13 September 2007). The Science of Harmonics in Classical Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139468626 . Retrieved 3 May 2015.(p. 187 "Meibom, Westphal")

- 1 2 A Briggman (12 January 2012). Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit. Oxford University Press, Oxford Early Christian Studies. ISBN 978-0199641536 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.("Distantia & Landels")

- ↑ Erik Nis Ostenfeld, Plato ( The Republic - Ergon and dynamis)- Forms, Matter and Mind Volume 10 of Martinus Nijhoff philosophy library Springer Science & Business Media, 1982 ISBN 940097681X [Retrieved 2015-05-08]

- ↑ definitions taken from bible hub - Strong's Concordance & Merriam-Webster [Retrieved 2015-05-08]

- ↑ Nathan Sidoli, Andrew Barker (October 2009). "Andrew Barker, The Science of Harmonics in Classical Greece reviewed by Nathan Sidoli, Waseda University". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009.10.38. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ I. Kagis McEwen - Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architecture, MIT Press 2003, p. 1 of 493 pages, ISBN 026263306X [Retrieved 2015-12-16]

- ↑ D.K.S. Walden - Frozen Music: Music and Architecture in Vitruvius’ De Architectura 2014 Greek and Roman Musical Studies, Volume 2, Issue 1, pages 124 – 145 DOI: 10.1163/22129758-12341255 [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ J. Prins - Echoes of an Invisible World: Marsilio Ficino and Francesco Patrizi on Cosmic Order and Music Theory BRILL, 28 November 2014, 476 pages, History, ISBN 9004281762, Brill's Studies in Intellectual History [Retrieved 2015-12-16]

- ↑ S.J. Livesey (John of Reading) (1989). Theology and Science in the Fourteenth Century: Three Questions on the Unity and Subalternation of the Sciences from John of Reading's Commentary on the Sentences. BRILL. p. 25. ISBN 978-9004090231 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Aristoxenus, P Marquard - Aristoxenou harmonikōn ta sōzomena: Die harmonischen fragmente des Aristoxenus Weidmann, 1868 [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ H.S. Macran - The harmonics of Aristonexus The Boston Library Consortium - Northeastern University Libraries [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ the Internet Archive - Open Library ID : OL14785002M University of Toronto MARC record [Retrieved 2015-05-08]

- ↑ T.J. Mathiesen (1999). Apollo's Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. University of Nebraska Press, ACLS Humanities E-Book Volume 2 of Center for the History of Music Theory and Literature Bloomington, Ind: Publications of the Center for the History of Music Theory and Literature. ISBN 978-0803230798 . Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ A. Barker - staff profile University of Birmingham [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ M Litchfield (1988). "Aristoxenus and Empiricism: A Reevaluation Based on His Theories". Journal of Music Theory. Journal of Music Theory Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring, 1988), pp. 51-73 Published by: Duke University Press. 32 (1): 51–73. doi:10.2307/843385. JSTOR 843385.

- ↑ N Cazden (1958). "Pythagoras and Aristoxenos Reconciled". Journal of the American Musicological Society. Journal of the American Musicological Society Vol. 11, No. 2/3 (Summer - Autumn, 1958), pp. 97-105 Published by: University of California Press. 11 (2/3): 97–105. doi:10.2307/829897. JSTOR 829897.

- ↑ Lilian Voudouri - Music Library of Greece Friends of Music Society (Athens) [Retrieved 2015-05-04]

- ↑ D Creese - Instruments and Empiricism in Aristoxenus' Elementa harmonica Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine Newcastle University - School of History Classics and Archaeology 2012 [Retrieved 2015-05-04]