Transport Workers Union of America (TWU) is a United States labor union that was founded in 1934 by subway workers in New York City, then expanded to represent transit employees in other cities, primarily in the eastern U.S. This article discusses the parent union and its largest local, Local 100, which represents the transport workers of New York City. TWU is a member of the AFL–CIO.

Boston police officers went on strike on September 9, 1919. They sought recognition for their trade union and improvements in wages and working conditions. Police Commissioner Edwin Upton Curtis denied that police officers had any right to form a union, much less one affiliated with a larger organization like the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which some attribute to concerns that unionized police would not protect the interest of city officials and business leaders. Attempts at reconciliation between the Commissioner and the police officers, particularly on the part of Boston's Mayor Andrew James Peters, failed.

Justice for Janitors (JfJ) is a social movement organization that fights for the rights of janitors across the US and Canada. It was started on June 15, 1990, in response to the low wages and minimal health-care coverage that janitors received. Justice for Janitors includes more than 225,000 janitors in at least 29 cities in the United States and at least four cities in Canada. Members fight for better wages, better conditions, improved healthcare, and full-time opportunities.

The Baltimore Police Strike was a 1974 labor action conducted by officers of the Baltimore Police Department. Striking officers sought better wages and changes to BPD policy. They also expressed solidarity with Baltimore municipal workers, who were in the midst of an escalating strike action that began on July 1. On July 7, police launched a campaign of intentional misbehavior and silliness; on July 11 they began a formal strike. The department reported an increase in fires and looting, and the understaffed BPD soon received support from Maryland State Police. The action ended on July 15, when union officials negotiated an end to both strikes. The city promised police officers a wage increase in 1975, but refused amnesty for the strikers. Police Commissioner Donald Pomerleau revoked the union's collective bargaining rights, fired its organizers, and pointedly harassed its members.

The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) is a labor union that represents teachers, paraprofessionals, and clinicians in the Chicago public school system. The union has consistently fought for improved pay, benefits, and job security for its members, and it has resisted efforts to vary teacher pay based on performance evaluations. It has also pushed for improvements in the Chicago schools, and since its inception argued that its activities benefited students as well as teachers.

Benjamin Aaron was an American attorney, labor law scholar and civil servant. He is known for his work as an arbitrator and mediator, and for helping to advance the development of the field of comparative labor law in the United States.

The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Jeremiah J. Horan was an organized crime figure and President of the Building Service Employees International Union from 1927 until his death in 1937. Although praised by newspapers for reducing the level of overt violence and graft which plagued the union under his predecessor, William Quesse, Horan nonetheless still engaged in bribery, extortion, physical intimidation, and other crimes, and permitted George Scalise to enter and rise within the organization. Horan established the kickback scheme whereby Scalise would eventually loot the union treasury of millions of dollars in member dues.

The 1912 New York City waiters’ strike began on May 7, 1912 at the Belmont Hotel and was the first general strike for waiters and hotel workers in New York City history. That day over 150 hotel workers walked out as a sign of protest against their poor working conditions. The strike was organized by Joseph James Ettor and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in conjunction with the Hotel Workers' International Union. At the height of the strike there were 54 hotels and 30 restaurants and other establishments without their staff. This amounted to 2,500 waiters, 1,000 cooks, and 3,000 other striking hotel workers. The strike continued through the rest of May but police began reprimanding protestors, making many of them go back to work. The strike officially ended on June 25, 1912.

The 1974 Baltimore municipal strike was a strike action undertaken by different groups of municipal workers in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. It was initiated by waste collectors seeking higher wages and better conditions. They were joined by sewer workers, zookeepers, prison guards, highway workers, recreation & parks workers, animal control workers, abandoned vehicles workers, and eventually by police officers. Trash piled up during the strike, and, especially with diminished police enforcement, many trash piles were set on fire. City jails were also a major site for unrest.

The Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (BRT) was a labor organization for railroad employees founded in 1883. Originally called the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen, its purpose was to negotiate contracts with railroad management and to provide insurance for members.

The Switchmen's Union of North America (SUNA) was a labor union formed in October 1894 that represented the track switch operators and people who coupled railway cars in railway yards in the United States and Canada. It became part of the United Transportation Union in 1969.

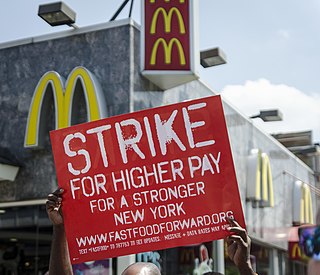

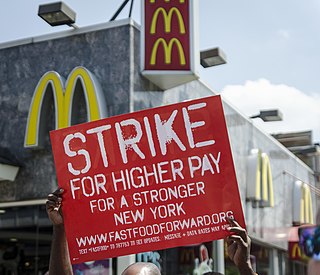

The Fight for $15 is an American political movement advocating for the minimum wage to be raised to USD$15 per hour. The federal minimum wage was last set at $7.25 per hour in 2009. The movement has involved strikes by child care, home healthcare, airport, gas station, convenience store, and fast food workers for increased wages and the right to form a labor union. The "Fight for $15" movement started in 2012, in response to workers' inability to cover their costs on such a low salary, as well as the stressful work conditions of many of the service jobs which pay the minimum wage.

The Burlington railroad strike of 1888 was a failed union strike which pitted the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, and the Switchmen's Mutual Aid Association (SMAA) against the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) its extensive trackage in the Midwestern United States. It was led by the skilled engineers and firemen, who demanded higher wages, seniority rights, and grievance procedures. It was fought bitterly by management, which rejected the very notion of collective bargaining. There was much less violence than the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, but after 10 months the very expensive company operation to permanently replace all the strikers was successful and the strike was a total defeat for them.

During the strike wave of 1945–46 a strike of almost 3,500 tugboat workers occurred on Monday February 1, 1946. The expectations of the strike were to bring the world's busiest harbor to a virtual standstill. Captain William Bradley, president of Local 333, United Maritime Division, International Longshoremen's Association, stated two days before the actual strike that a strike vote had been taken the previous week-end, during a breakdown of negotiations with the Employers Wage Adjustment Committee, which represents the owners and operators in this port.

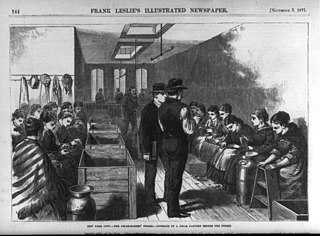

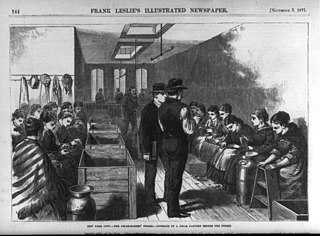

The cigar makers' strike of New York lasted from mid-October 1877 until mid-February 1878. Ten thousand workers walked out at the height of the strike, demanding better wages, shorter hours and better working conditions, especially in the tenement manufacturing locations. The strike was supported by the Cigar Makers International Union of America, local chapter 144.

The New England Shoemakers Strike of 1860 began on February 22, 1860 with 3,000 shoemakers walking off their jobs in Lynn, Massachusetts. It ended in April with modest gains for shoemakers, including pay increases and owner recognition of some labor unions. Approximately 20,000 workers went on strike across New England which made it the largest mass walkout in American history prior to the Civil War.

The Atlanta streetcar strike of 1916 was a labor strike involving streetcar operators for the Georgia Railway and Power Company in Atlanta, Georgia. Precipitated by previous strike action by linemen of Georgia Railway earlier that year, the strike began on September 30 and ended January 5 of the following year. The main goals of the strike included increased pay, shorter working hours, and union recognition. The strike ended with the operators receiving a wage increase, and subsequent strike action the following year lead to union recognition.

The 1949 New York City brewery strike was a labor strike involving approximately 7,000 brewery workers from New York City. The strike began on April 1 of that year after a labor contract between 7 local unions of the Brewery Workers Union and the Brewers Board of Trade expired without a replacement. The primary issue was over the number of workers on board delivery trucks, with the union wanting two workers per truck as opposed to the companies' standard one person per truck. Additional issues regarded higher wages and reduced working hours for the union members, among other minor issues.

The 1949 New York City taxicab strike was a labor strike involving taxicab drivers in New York City. The strike was the result of union organization efforts carried out by a local union of the United Mine Workers who were seeking union recognition and pay increases for taxicab drivers in the city. The strike started on April 1, 1949 and was initially successful in shutting down approximately 80% of taxicab operations in the city. However, after several days, taxicab operators used strikebreakers and countered the effectiveness of the strike. The UMW officially ended the strike on April 8. Historian Graham Russell Gao Hodges claims that the UMW's mismanagement of the strike was the primary reason for its failure and states that the strike "did not result in any positive results" for the strikers.