Empress Dowager Cixi was a Manchu noblewoman of the Yehe Nara clan who effectively controlled the Chinese government in the late Qing dynasty as empress dowager and regent for almost 50 years, from 1861 until her death in 1908. Selected as a concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor in her adolescence, she gave birth to a son, Zaichun, in 1856. After the Xianfeng Emperor's death in 1861, his five-year-old son became the Tongzhi Emperor, and Cixi assumed the role of co-empress dowager alongside Xianfeng's widow, Empress Dowager Ci'an. Cixi ousted a group of regents appointed by the late emperor and assumed the regency along with Ci'an. Cixi then consolidated control over the dynasty when she installed her nephew as the Guangxu Emperor at the death of the Tongzhi Emperor in 1875. Ci'an continued as co-regent until her death in 1881.

The Guangxu Emperor, also known by his temple name Emperor Dezong of Qing, personal name Zaitian, was the tenth emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign was largely dominated by his maternal aunt Empress Dowager Cixi. He initiated the radical Hundred Days' Reform but was abruptly stopped when the Empress Dowager launched a coup in 1898, after which he was held under virtual house arrest until his death.

The Tongzhi Emperor, also known by his temple name Emperor Muzong of Qing, personal name Zaichun, was the ninth emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the eighth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign, which effectively lasted through his adolescence, was largely overshadowed by the rule of Empress Dowager Cixi. Although he had little influence over state affairs, the events of his reign gave rise to what historians call the "Tongzhi Restoration", an unsuccessful modernization program.

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor and his reform-minded supporters. Following the issuing of the reformative edicts, a coup d'état was perpetrated by powerful conservative opponents led by Empress Dowager Cixi. While Empress Dowager Cixi supported the principles of the Hundred Days' Reform, she feared that sudden implementation, without bureaucratic support, would be disruptive and that the Japanese and other foreign powers would take advantage of any weakness. She later backed the late Qing reforms after the invasions of the Eight-Nation Alliance.

Empress Xiaozhenxian, of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner Niohuru clan, was a posthumous name bestowed to the wife and empress consort of Yizhu, the Xianfeng Emperor. She was empress consort of Qing from 1852 until her husband's death in 1861, after which she was honored as Empress Dowager Ci'an.

Kang Youwei was a prominent political thinker and reformer in China of the late Qing dynasty. His increasing closeness to and influence over the young Guangxu Emperor sparked conflict between the emperor and his adoptive mother, the regent Empress Dowager Cixi. His ideas were influential in the abortive Hundred Days' Reform. Following the coup by Cixi that ended the reform, Kang was forced to flee. He continued to advocate for a Chinese constitutional monarchy after the founding of the Republic of China.

Yixuan, formally known as Prince Chun, was an imperial prince of the House of Aisin-Gioro and a statesman of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in China. He was the father of the Guangxu Emperor, and the paternal grandfather of Puyi through his fifth son Zaifeng.

Jung Chang is a Chinese-born British author. She is best known for her family autobiography Wild Swans, selling over 10 million copies worldwide but banned in the People's Republic of China. Her 832-page biography of Mao Zedong, Mao: The Unknown Story, written with her husband, the Irish historian Jon Halliday, was published in June 2005.

Yehe Nara Jingfen, of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner Yehe Nara clan, was the wife and empress consort of Zaitian, the Guangxu Emperor. She was empress consort of Qing from 1889 until her husband's death in 1908, after which she was honoured as Empress Dowager Longyu. She was posthumously honoured with the title Empress Xiaodingjing.

Imperial Noble Consort Keshun, of the Manchu Bordered Red Banner Tatara clan, was a consort of the Guangxu Emperor. She was five years his junior. She was known to foreigners as the Pearl Consort. Legend has it that she was drowned in a well on the orders of Empress Dowager Cixi.

Imperial Noble Consort Wenjing, also known as Dowager Imperial Noble Consort Duankang, of the Manchu Bordered Red Banner Tatara clan, was a consort of the Guangxu Emperor.

Empress Xiaozheyi, of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner Alut clan, was a posthumous name bestowed to the wife and empress consort of Zaichun, the Tongzhi Emperor. She was empress consort of Qing from 1872 until her husband's death in 1875, after which she was honoured as Empress Jiashun.

Ronglu, courtesy name Zhonghua, was a Manchu political and military leader of the late Qing dynasty. He was born in the Guwalgiya clan, which was under the Plain White Banner of the Manchu Eight Banners. Deeply favoured by Empress Dowager Cixi, he served in a number of important civil and military positions in the Qing government, including the Zongli Yamen, Grand Council, Grand Secretary, Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Trade Minister, Secretary of Defence, Nine Gates Infantry Commander, and Wuwei Corps Commander. He was also the maternal grandfather of Puyi, the last Emperor of China and the Qing dynasty.

Imperial Noble Consort Xianzhe, of the Manchu Bordered Blue Banner Hešeri clan, was a consort of the Tongzhi Emperor.

Six gentlemen of the Hundred Days' Reform, also known as Six gentlemen of Wuxu, were a group of six Chinese intellectuals whom the Empress Dowager Cixi had arrested and executed for their attempts to implement the Hundred Days' Reform. The most vocal and prominent member in the group of six was Tan Sitong. Kang Guangren was notable as the younger brother of the reformist leader Kang Youwei. These executions were a part of the large purge in which about 30 men were arrested, imprisoned, dismissed from office, or banished. In many cases the family members of these men were arrested as well.

An Dehai was a palace eunuch at the imperial court of the Qing dynasty. In the 1860s, he became the confidant and favourite of Empress Dowager Cixi and was subsequently executed as part of a power struggle between the empress dowager and Prince Chun.

Sai Jinhua was a Chinese prostitute who became the acquaintance of Alfred von Waldersee. Her real family name was Cao or Zhao. During her career, she used the names Fu Caiyun (傅彩雲), Sai Jinhua, and Cao Menglan (曹夢蘭). Her art name (hao) was Weizhao Lingfei (魏趙靈飛). Some people referred to her as Sai Erye (賽二爺).

Hong Jun was a Chinese diplomat. From 1887 to 1890 he had served as a special emissary of the Qing dynasty government to Russia, Germany, the Netherlands, and Austria.

![<i>Sorrows of the Forbidden City</i> 1948 [[Cinema of China|China]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Qinggongmishi.jpeg/320px-Qinggongmishi.jpeg)

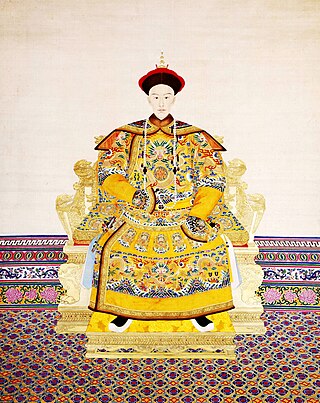

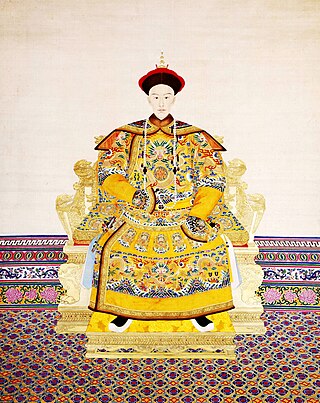

Sorrows of the Forbidden City is a Mandarin Chinese film released in 1948. It was directed by Zhu Shilin and filmed in Hong Kong. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the film was criticized as "treasonous" for its positive depiction of the Emperor. However, its reputation has risen in recent years, and it was ranked as the 37th best Chinese film of all time in the Hong Kong Film Awards poll of 2013.

Nellie Yu Roung Ling, also spelt Nelly, was a Hanjun Plain White bannerwoman and dancer, who is considered "the first modern dancer of China". She was the younger daughter of Yu Keng and Louisa Pierson, the other one being Lizzie Yu Der Ling. Although not a member of the Qing imperial family, Roung Ling was given the title of "commandery princess" while serving as a lady-in-waiting for Empress Dowager Cixi.:268 She was also known as Yu Roon(g) Ling, especially in the works of her sister Der Ling.:267 She was referred to as Madame Dan Pao Tchao after her marriage to the General Dan Pao Tchao, and Princess Shou Shan, a title appeared on the cover of her 1934 historical novella about the Fragrant Concubine, a name Sir Reginald Johnston claimed she never used.:xii

![<i>Sorrows of the Forbidden City</i> 1948 [[Cinema of China|China]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Qinggongmishi.jpeg/320px-Qinggongmishi.jpeg)