Related Research Articles

Henry Louis Mencken was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, and contemporary movements. His satirical reporting on the Scopes Trial, which he dubbed the "Monkey Trial", also gained him attention. The term "Menckenian" has entered multiple dictionaries to describe anything of or pertaining to Mencken, including his combative rhetorical and prose style.

British Israelism is the British nationalist, pseudoarchaeological, pseudohistorical and pseudoreligious belief that the people of Great Britain are "genetically, racially, and linguistically the direct descendants" of the Ten Lost Tribes of ancient Israel. With roots in the 16th century, British Israelism was inspired by several 19th century English writings such as John Wilson's 1840 Our Israelitish Origin. From the 1870s onward, numerous independent British Israelite organizations were set up throughout the British Empire as well as in the United States; as of the early 21st century, a number of these organizations are still active. In the United States, the idea gave rise to the Christian Identity movement.

Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life is a 1925 documentary film that follows a branch of the Bakhtiari tribe of Lurs in Persia as they and their herds make their seasonal journey to better pastures. It is considered one of the earliest ethnographic documentary films. In 1997, Grass was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, essayist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced", and William Faulkner called him "the father of American literature". His novels include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), with the latter often called the "Great American Novel". Twain also wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) and Pudd'nhead Wilson (1894), and co-wrote The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873) with Charles Dudley Warner.

In the United States, White Anglo-Saxon Protestants or WASPs is a sociological term which is often used to describe white Protestant Americans who are generally part of the white dominant culture or upper-class and historically often the Mainline Protestant elite. Historically or most consistently, WASPS are of British descent, though the definition of WASP varies in this respect. WASPs have dominated American society, culture, and politics for most of the history of the United States. Critics have disparaged them as "The Establishment". Although the social influence of wealthy WASPs has declined since the 1960s, the group continues to play a central role in American finance, politics and philanthropy.

[Date: 1601.] Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors. or simply 1601 is the title of a short risqué squib by Mark Twain, first published anonymously in 1880, and finally acknowledged by the author in 1906.

The Savage Club, founded in 1857, is a gentlemen's club in London, named after the poet, Richard Savage. Members are drawn from the fields of art, drama, law, literature, music or science.

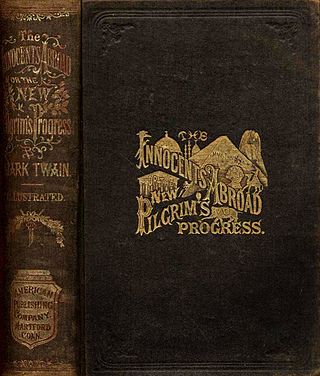

The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims' Progress is a travel book by American author Mark Twain. Published in 1869, it humorously chronicles what Twain called his "Great Pleasure Excursion" on board the chartered steamship Quaker City through Europe and the Holy Land with a group of American travelers in 1867. The five-month voyage included numerous side trips on land.

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the 5th and 8th centuries AD, during the initial period of Early Medieval England. A variant of Germanic paganism found across much of north-western Europe, it encompassed a heterogeneous variety of beliefs and cultic practices, with much regional variation.

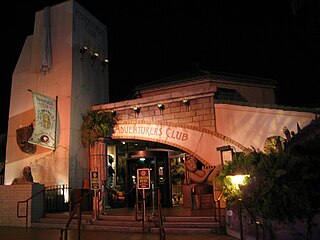

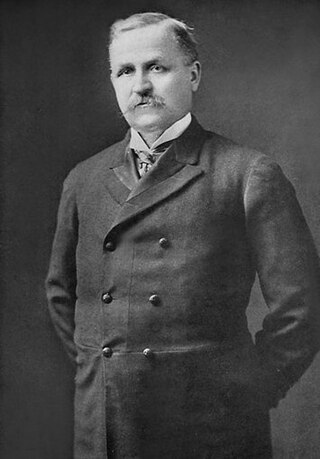

Moses Taylor Pyne, was an American financier and philanthropist, and one of Princeton University's greatest benefactors and its most influential trustee.

The Adventurers Club was a themed nightclub in Pleasure Island at the Walt Disney World Resort. It was styled after a private club for world travelers and explorers and was set in 1937. The walls of the club were covered with artifacts and photographs from various explorations. The Adventurers Club featured animatronics, puppets, and a cast of adventurers who performed in shows and improvisational comedy while mingling with the club's patrons. Shows and conversation were often laced with innuendo, and the patrons might have been welcomed as guests, given fictitious names and "recognized" as fellow adventurers, or simply referred to as "drunks".

Charles Adiel Lewis Totten was an American military officer, a professor of military tactics, a prolific writer, and an early advocate of British Israelism.

Mark Twain: The Musical is a stage musical biography of Mark Twain that had a ten-year summertime run in Elmira, NY and Hartford, CT (1987–1995) and was telecast on a number of public television stations. An original cast CD was released by Premier Recordings in 1988, and LML Music in 2009 issued a newly mastered and complete version of the score. Video and DVD versions of the show are currently in release.

William Scott Ament was a missionary to China for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) from 1877, and was known as the "Father of Christian Endeavor in China." Ament became prominent as a result of his activism during the Boxer Uprising and controversial in its aftermath because of the personal attacks on him by American writer Mark Twain for his collection of punitive indemnities from northern Chinese villages.

The Lotos Club is a private social club in New York City. Founded primarily by a young group of writers and critics in 1870 as a gentlemen's club, it has since begun accepting women as members. Mark Twain, an early member, called it the "Ace of Clubs". The Club took its name from the poem "The Lotos-Eaters" by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, which was then very popular. Lotos was thought to convey an idea of rest and harmony. Two lines from the poem were selected for the Club motto:

In the afternoon they came unto a land In which it seemed always afternoon

Young's Hotel (1860–1927) in Boston, Massachusetts, was located on Court Street in the Financial District, in a building designed by William Washburn. George Young established the business, later taken over by Joseph Reed Whipple and George G. Hall. Guests at Young's included Mark Twain, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, Rutherford B. Hayes, and numerous others.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , well known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist. Twain is noted for his novels Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), which has been called the "Great American Novel," and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876). He also wrote poetry, short stories, essays, and non-fiction. His big break was "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" (1867).

Herbert Adams Gibbons was an American journalist who wrote about international politics and European colonialism during the early 20th century. He is best known for his books, The New Map of Asia, The New Map of Africa, and The New Map of Europe. He is also known for his seminal study, The Foundation of the Ottoman Empire, which he wrote in Istanbul during the early 20th century.

The Adventurers' Club of New York was an adventure-oriented private men's club founded in New York City in 1912 by Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, editor of the popular pulp magazine Adventure. There were 34 members at the first meeting. In its second year, "Sinclair Lewis, Hoffman's assistant, was elected secretary and served three years." Monthly dinner meetings, and weekly luncheons, were the primary functions of the club.

Chapters from My Autobiography are 25 pieces of autobiographical work published by American author Mark Twain in the North American Review between September 1906 and December 1907. Rather than following the standard form of an autobiography, they comprise a rambling collection of anecdotes and ruminations. Much of the text was dictated.

References

- ↑ "Ends of the Earthers Foregather Here Again: And Astonish Mark Twain with Some Very Brief Reports," New York Times, Feb. 17, 1906, at 9.

- ↑ "Gathered From the Ends of the Earth to Dine," The New York Times , March 31, 1904, at 5.

- ↑ "Ends of the Earth Club Dinner, The New York Times, Dec. 4, 1920, at 16.

- 1 2 Paul Fatout, ed., Mark Twain Speaking, at 147.