In graph theory, the girth of an undirected graph is the length of a shortest cycle contained in the graph. If the graph does not contain any cycles, its girth is defined to be infinity. For example, a 4-cycle (square) has girth 4. A grid has girth 4 as well, and a triangular mesh has girth 3. A graph with girth four or more is triangle-free.

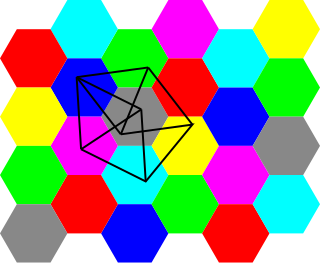

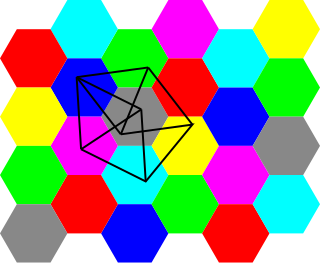

In combinatorial mathematics, Ramsey's theorem, in one of its graph-theoretic forms, states that one will find monochromatic cliques in any edge labelling of a sufficiently large complete graph. To demonstrate the theorem for two colours, let r and s be any two positive integers. Ramsey's theorem states that there exists a least positive integer R(r, s) for which every blue-red edge colouring of the complete graph on R(r, s) vertices contains a blue clique on r vertices or a red clique on s vertices.

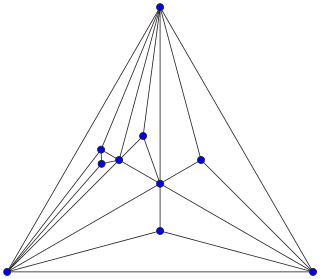

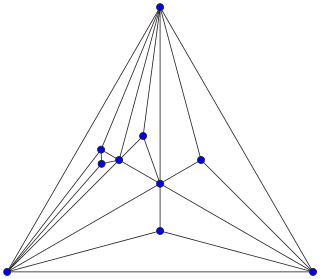

The Sylvester–Gallai theorem in geometry states that every finite set of points in the Euclidean plane has a line that passes through exactly two of the points or a line that passes through all of them. It is named after James Joseph Sylvester, who posed it as a problem in 1893, and Tibor Gallai, who published one of the first proofs of this theorem in 1944.

In mathematics, incidence geometry is the study of incidence structures. A geometric structure such as the Euclidean plane is a complicated object that involves concepts such as length, angles, continuity, betweenness, and incidence. An incidence structure is what is obtained when all other concepts are removed and all that remains is the data about which points lie on which lines. Even with this severe limitation, theorems can be proved and interesting facts emerge concerning this structure. Such fundamental results remain valid when additional concepts are added to form a richer geometry. It sometimes happens that authors blur the distinction between a study and the objects of that study, so it is not surprising to find that some authors refer to incidence structures as incidence geometries.

The no-three-in-line problem in discrete geometry asks how many points can be placed in the grid so that no three points lie on the same line. This number is at most , because points in a grid would include a row of three or more points, by the pigeonhole principle. The problem was introduced by Henry Dudeney in 1900. Brass, Moser, and Pach call it "one of the oldest and most extensively studied geometric questions concerning lattice points".

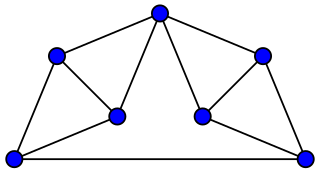

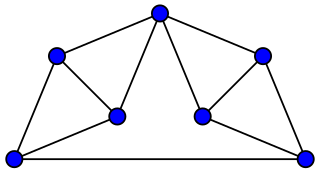

In mathematics, the "happy ending problem" is the following statement:

In geometric graph theory, the Hadwiger–Nelson problem, named after Hugo Hadwiger and Edward Nelson, asks for the minimum number of colors required to color the plane such that no two points at distance 1 from each other have the same color. The answer is unknown, but has been narrowed down to one of the numbers 5, 6 or 7. The correct value may depend on the choice of axioms for set theory.

Geometric graph theory in the broader sense is a large and amorphous subfield of graph theory, concerned with graphs defined by geometric means. In a stricter sense, geometric graph theory studies combinatorial and geometric properties of geometric graphs, meaning graphs drawn in the Euclidean plane with possibly intersecting straight-line edges, and topological graphs, where the edges are allowed to be arbitrary continuous curves connecting the vertices, thus it is "the theory of geometric and topological graphs". Geometric graphs are also known as spatial networks.

In the mathematical field of graph theory, Fáry's theorem states that any simple, planar graph can be drawn without crossings so that its edges are straight line segments. That is, the ability to draw graph edges as curves instead of as straight line segments does not allow a larger class of graphs to be drawn. The theorem is named after István Fáry, although it was proved independently by Klaus Wagner (1936), Fáry (1948), and Sherman K. Stein (1951).

In mathematics, and particularly geometric graph theory, a unit distance graph is a graph formed from a collection of points in the Euclidean plane by connecting two points by an edge whenever the distance between the two points is exactly one. Edges of unit distance graphs sometimes cross each other, so they are not always planar; a unit distance graph without crossings is called a matchstick graph.

A thrackle is an embedding of a graph in the plane, such that each edge is a Jordan arc and every pair of edges meet exactly once. Edges may either meet at a common endpoint, or, if they have no endpoints in common, at a point in their interiors. In the latter case, the crossing must be transverse.

The Erdős–Anning theorem states that an infinite number of points in the plane can have mutual integer distances only if all the points lie on a straight line. It is named after Paul Erdős and Norman H. Anning, who published a proof of it in 1945.

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, the Moser spindle is an undirected graph, named after mathematicians Leo Moser and his brother William, with seven vertices and eleven edges. It is a unit distance graph requiring four colors in any graph coloring, and its existence can be used to prove that the chromatic number of the plane is at least four.

In geometric graph theory, a branch of mathematics, a matchstick graph is a graph that can be drawn in the plane in such a way that its edges are line segments with length one that do not cross each other. That is, it is a graph that has an embedding which is simultaneously a unit distance graph and a plane graph. For this reason, matchstick graphs have also been called planar unit-distance graphs. Informally, matchstick graphs can be made by placing noncrossing matchsticks on a flat surface, hence the name.

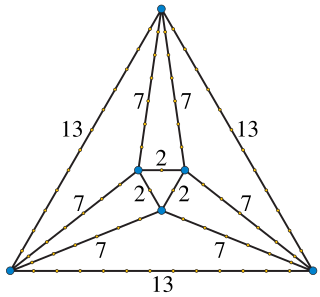

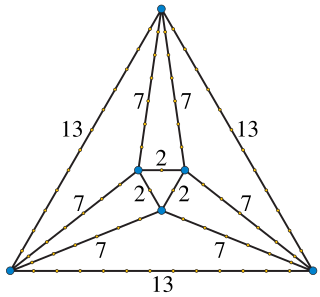

In combinatorial mathematics, an Apollonian network is an undirected graph formed by a process of recursively subdividing a triangle into three smaller triangles. Apollonian networks may equivalently be defined as the planar 3-trees, the maximal planar chordal graphs, the uniquely 4-colorable planar graphs, and the graphs of stacked polytopes. They are named after Apollonius of Perga, who studied a related circle-packing construction.

In mathematics, Harborth's conjecture states that every planar graph has a planar drawing in which every edge is a straight segment of integer length. This conjecture is named after Heiko Harborth, and would strengthen Fáry's theorem on the existence of straight-line drawings for every planar graph. For this reason, a drawing with integer edge lengths is also known as an integral Fáry embedding. Despite much subsequent research, Harborth's conjecture remains unsolved.

In geometry, the distance set of a collection of points is the set of distances between distinct pairs of points. Thus, it can be seen as the generalization of a difference set, the set of distances in collections of numbers.

In combinatorial mathematics and extremal graph theory, the Ruzsa–Szemerédi problem or (6,3)-problem asks for the maximum number of edges in a graph in which every edge belongs to a unique triangle. Equivalently it asks for the maximum number of edges in a balanced bipartite graph whose edges can be partitioned into a linear number of induced matchings, or the maximum number of triples one can choose from points so that every six points contain at most two triples. The problem is named after Imre Z. Ruzsa and Endre Szemerédi, who first proved that its answer is smaller than by a slowly-growing factor.