Epic of Erra

In the epic that is given the modern title Erra, the writer Kabti-ilani-Marduk, [3] a descendant, he says, of Dabibi, presents himself [4] in a colophon following the text as simply the transcriber of a visionary dream in which Erra himself revealed the text.

The poem opens with an invocation. The god Erra is sleeping fitfully with his consort (identified with Mamītum and not with the mother goddess Mami) [5] [6] but is roused by his advisor Išum and the Seven (Sibitti or Sebetti), who are the sons of heaven and earth [7] —"champions without peer" is the repeated formula—and are each assigned a destructive destiny by Anu. Machinist and Sasson (1983) call them "personified weapons". The Sibitti call on Erra to lead the destruction of mankind. Išum tries to mollify Erra's wakened violence, to no avail. Foreign peoples invade Babylonia, but are struck down by plague. Even Marduk, the patron of Babylon, relinquishes his throne to Erra for a time. Tablets II and III are occupied with a debate between Erra and Išum. Erra goes to battle in Babylon, Sippar, Uruk, Dūr-Kurigalzu and Dēr. The world is turned upside down: righteous and unrighteous are killed alike. Erra orders Išum to complete the work by defeating Babylon's enemies. Then the god withdraws to his own seat in Emeslam with the terrifying Seven, and mankind is saved. A propitiatory prayer ends the work.

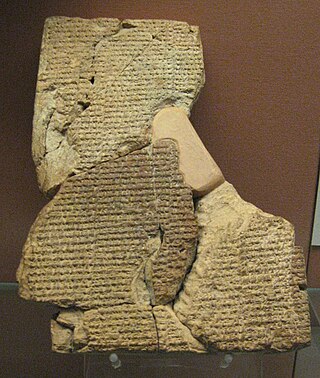

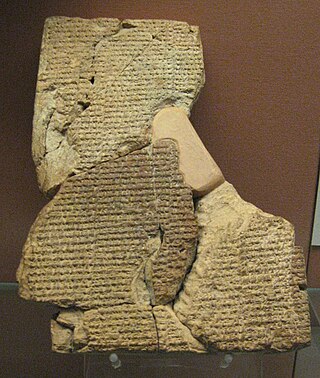

The poem must have been central to Babylonian culture: at least thirty-six copies have been recovered from five first-millennium sites—Assur, Babylon, Nineveh, Sultantepe and Ur [8] —more, even, as the assyriologist and historian of religions Luigi Giovanni Cagni points out, than have been recovered of the Epic of Gilgamesh . [9]

The text appears to some readers to be a mythologisation of historic turmoil in Mesopotamia, though scholars disagree as to the historic events that inspired the poem: the poet exclaims (tablet IV:3) "You changed out of your divinity and made yourself like a man."

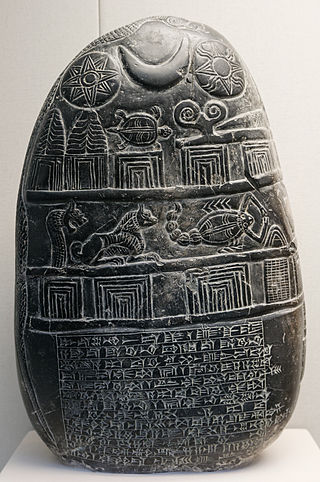

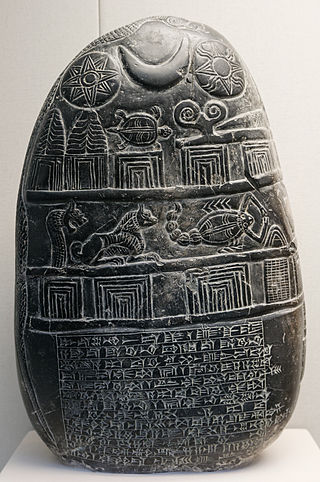

The Erra text soon assumed magical functions [10] Parts of the text were inscribed on amulets employed for exorcism and as a prophylactic against the plague. The Seven are known from a range of Akkadian incantation texts: their demonic names vary, [11] but their number, seven, is invariable.

The five tablets containing the Erra epos were first published in 1956, [12] with an improved text, based on additional finds, appearing in 1969. [13] Perhaps 70% of the poem has been recovered. [14]

Walter Burkert [15] noted the consonance of the purely mythic seven led by Erra with the Seven against Thebes, widely assumed by Hellenists to have had a historical basis.

Akkadian literature is the ancient literature written in the Akkadian language in Mesopotamia during the period spanning the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age.

Nergal was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations under indicating his cult survived into the period of Achaemenid domination. He was primarily associated with war, death, and disease, and has been described as the "god of inflicted death". He reigned over Kur, the Mesopotamian underworld, depending on the myth either on behalf of his parents Enlil and Ninlil, or in later periods as a result of his marriage with the goddess Ereshkigal. Originally either Mammitum, a goddess possibly connected to frost, or Laṣ, sometimes assumed to be a minor medicine goddess, were regarded as his wife, though other traditions existed, too.

In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the sea, mating with Abzû, the god of the groundwater, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation. She is referred to as a woman and described as "the glistening one". It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos. In the first, she is a creator goddess, through a sacred marriage between different waters, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second Chaoskampf Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.

Mammitum, Mammitu or Mammi was a Mesopotamian goddess viewed as the wife of Nergal, the god of death. Mammitum's name might mean “oath” or “frost”. In the earliest sources she is Nergal's most commonly attested wife, but from the Kassite period onward she was often replaced in this role by the goddess Laṣ.

The Anunnaki are a group of deities of the ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians. In the earliest Sumerian writings about them, which come from the Post-Akkadian period, the Anunnaki are deities in the pantheon, descendants of An and Ki, the god of the heavens and the goddess of earth, and their primary function was to decree the fates of humanity.

The Enūma Eliš is the Babylonian creation myth. It was recovered by English archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1849 in the ruined Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. A form of the myth was first published by English Assyriologist George Smith in 1876; active research and further excavations led to near completion of the texts and improved translation.

Babylonian religion is the religious practice of Babylonia. Babylonian mythology was greatly influenced by their Sumerian counterparts and was written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myths were usually either written in Sumerian or Akkadian. Some Babylonian texts were translations into Akkadian from the Sumerian language of earlier texts, although the names of some deities were changed.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a Sumerian city state positioned east of the Tigris on the border between Sumer and Elam. It is known that he was a judge deity, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself.

Ut-napishtim or Uta-na’ishtim, Atra-Hasis, Ziusudra (Sumerian), Xisuthros is a character in ancient Mesopotamian mythology. He is tasked by the god Enki to create a giant ship to be called Preserver of Life in preparation of a giant flood that would wipe out all life. The character appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Apkallu (Akkadian) and Abgal are terms found in cuneiform inscriptions that in general mean either "wise" or "sage".

Ishum was a Mesopotamian god of Akkadian origin. He is best attested as a divine night watchman, tasked with protecting houses at night, but he was also associated with various underworld deities, especially Nergal and Shubula. He was associated with fire, but was not exclusively a fire god unlike Girra or Gibil. While he was not considered to be one of the major gods, he was commonly worshiped and appears in many theophoric names.

Kakka was a Mesopotamian god best known as the sukkal of Anu and Anshar. His cult center was Maškan-šarrum, most likely located in the north of modern Iraq on the banks of the Tigris.

The Sebitti or Sebittu are a group of seven minor war gods in Neo-Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and especially Assyrian tradition. They also appear in sources from Emar. Multiple different interpretations of the term occur in Mesopotamian literature.

Nabû-apla-iddina, inscribed mdNábû-ápla-iddinana or mdNábû-apla-íddina; reigned about 886–853 BC, was the sixth king of the dynasty of E of Babylon and he reigned for at least thirty-two years. During much of Nabû-apla-iddina's reign Babylon faced a significant rival in Assyria under the rule of Ashurnasirpal II. Nabû-apla-iddina was able to avoid both outright war and significant loss of territory. There was some low level conflict, including a case where he sent a party of troops led by his brother to aid rebels in Suhu. Later in his reign Nabu-apla-iddina agreed to a treaty with Ashurnasirpal II’s successor Shalmaneser III. Internally Nabu-apla-iddina worked on the reconstruction of temples and something of a literary revival took place during his reign with many older works being recopied.

Anu or Anum, originally An, was the divine personification of the sky, King of the gods, and ancestor of many of the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. He was regarded as a source of both divine and human kingship, and opens the enumerations of deities in many Mesopotamian texts. At the same time, his role was largely passive, and he was not commonly worshiped. It is sometimes proposed that the Eanna temple located in Uruk originally belonged to him, rather than Inanna, but while he is well attested as one of its divine inhabitants, there is no evidence that the main deity of the temple ever changed, and Inanna was already associated with it in the earliest sources. After it declined, a new theological system developed in the same city under Seleucid rule, resulting in Anu being redefined as an active deity. As a result he was actively worshiped by inhabitants of the city in the final centuries of history of ancient Mesopotamia.

Sumerian religion was the religion practiced by the people of Sumer, the first literate civilization of ancient Mesopotamia. The Sumerians regarded their divinities as responsible for all matters pertaining to the natural and social orders.

Adad-apla-iddina, typically inscribed in cuneiform mdIM-DUMU.UŠ-SUM-na, mdIM-A-SUM-na or dIM-ap-lam-i-din-[nam] meaning the storm god “Adad has given me an heir”, was the 8th king of the 2nd Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon and ruled c. 1064–1043. He was a contemporary of the Assyrian King Aššur-bêl-kala and his reign was a golden age for scholarship.

An = Anum, also known as the Great God List, is the longest preserved Mesopotamian god list, a type of lexical list cataloging the deities worshiped in the Ancient Near East, chiefly in modern Iraq. While god lists are already known from the Early Dynastic period, An = Anum has most likely only been composed in the Kassite period.

Laṣ (dLa-aṣ), also transcribed Laz, was a Mesopotamian goddess who was commonly regarded as the wife of Nergal, a god associated with war and the underworld. Instances of both conflation and coexistence of her and another goddess this position was attributed to, Mammitum, are attested in known sources.

Erragal or Errakal was a Mesopotamian god presumed to be related to Erra. However, there is no agreement about the nature of the connection between them in Assyriology. While Erragal might have been associated with storms and the destruction caused by them, he is chiefly attested as a benevolent deity, for example as an astral god with apotropaic functions. He was regarded as the husband of the goddess Ninšar, the divine butcher of Ekur, and they could be represented as a pair of stars in astronomical treatises such as MUL.APIN. References to worship of Erragal are uncommon, though he nonetheless appears in a variety of sources from the Isin-Larsa period to Neo-Babylonian times. He also appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh and in Atra-Hasis as a deity linked to the great flood.