William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American-born Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After completing graduate work at the Friedrich Wilhelm University and Harvard University, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology, and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

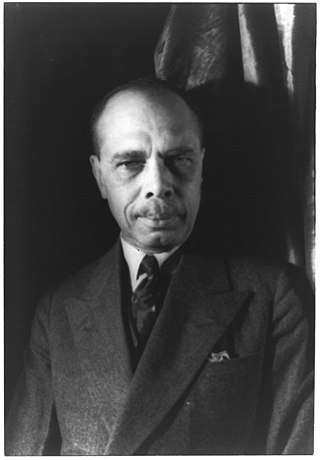

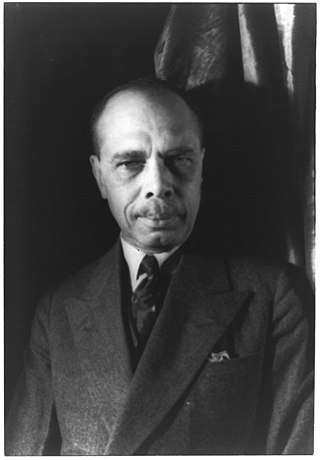

James Weldon Johnson was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920, he was chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novel, and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of black culture. He wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing", which later became known as the Negro National Anthem, the music being written by his younger brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson.

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ was a Jamaican-American writer and poet. He was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Angelina Weld Grimké was an African-American journalist, teacher, playwright, and poet.

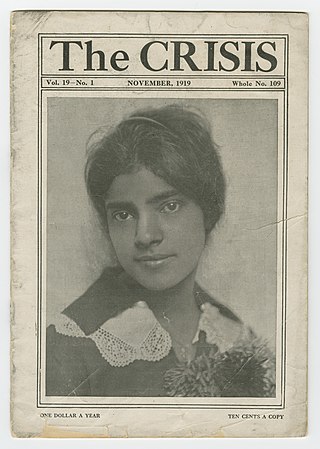

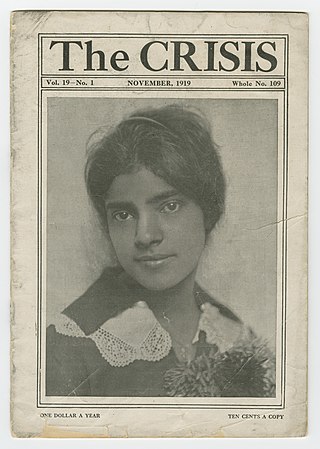

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest Black-oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

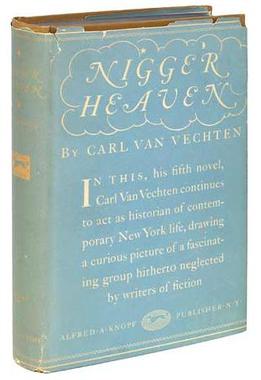

Nigger Heaven is a novel written by Carl Van Vechten, and published in October 1926. The book is set during the Harlem Renaissance in the United States in the 1920s. The book and its title have been controversial since its publication.

Regina M. Anderson was an American playwright and librarian. She was of Native American, Jewish, East Indian, Swedish, and other European ancestry ; one of her grandparents was of African descent, born in Madagascar. Despite her own identification of her race as "American," she was perceived to be African-American by others. Influenced by Ida B. Wells and the lack of Black history teachings in school, Anderson became a key member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Archibald Henry Grimké was an African American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for rights for blacks, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. branch.

Georgia Blanche Douglas Camp Johnson, better known as Georgia Douglas Johnson, was a poet and playwright. She was one of the earliest female African-American playwrights, and an important figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

"New Negro" is a term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance implying a more outspoken advocacy of dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. The term "New Negro" was made popular by Alain LeRoy Locke in his anthology The New Negro.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African-American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African-American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Eulalie Spence was a writer, teacher, director, actress and playwright from the British West Indies. She was an influential member of the Harlem Renaissance, writing fourteen plays, at least five of which were published. Spence, who described herself as a "folk dramatist" who made plays for fun and entertainment, was considered one of the most experienced female playwrights before the 1950s, and received more recognition than other black playwrights of the Harlem Renaissance period, winning several competitions. She presented several plays with W.E.B. Du Bois' Krigwa Players, of which she was a member from 1926 to 1928. Spence was also a mentor to theatrical producer Joseph Papp, founder of The Public Theater and the accompanying festival currently known as Shakespeare in the Park.

St. Mark's African Methodist Episcopal Church is a historic African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church in Duluth, Minnesota, United States. St. Mark's has played a central role in Duluth's African-American community for more than 125 years. While other black organizations have dissolved or moved to the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area, St. Mark's has been a local mainstay.

Irene Levine Paull was a writer and labor activist from Minnesota. She responded to discrimination by fighting for the rights of people who were oppressed. She was active in labor organizing and Communist politics, and she insisted that women could travel and write professionally just as men could. She founded the newspaper that became the Minneapolis Labor Review, penned columns under feminine pseudonyms, and wrote poetry, plays, and fiction that addressed themes of injustice.

The Krigwa Players was one of the most prominent and popular theatre groups based out of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. Though it only lasted for three years, The Krigwa Players' impact was felt throughout Harlem and the cities it spawned offshoot projects into, these cities being Cleveland, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and even Philadelphia. It was founded in 1925 by W.E.B. Du Bois and Regina Anderson, with Du Bois serving as the chairman of the theater group entirely. The theatre was converted from the basement of the 135th street Harlem Library. The goal of the company was focusing on creating, nurturing, developing, and promoting new writers, directors, performers, and actors within the black community.

The Brownies' Book was the first magazine published for African-American children and youth. Its creation was mentioned in the yearly children's issue of The Crisis in October 1919. The first issue was published during the Harlem Renaissance in January 1920, with issues published monthly until December 1921. It is cited as an "important moment in literary history" for establishing black children's literature in the United States.

Nellie F. Griswold Francis was an African-American suffragist, civic leader, and civil rights activist. Francis founded and led the Everywoman Suffrage Club, an African-American suffragist group which helped win women the right to vote in Minnesota. She initiated, drafted, and lobbied for the adoption of a state anti-lynching bill that was signed into law in 1921. When she and her lawyer husband, William T. Francis, bought a home in a white neighborhood, they were the targets of a Ku Klux Klan terror campaign. In 1927, she moved to Monrovia, Liberia, with her husband when he was appointed U.S. envoy to Liberia. He died there from yellow fever in 1929. Francis is one of 25 women honored for their roles in achieving the women's right to vote in the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Memorial on the grounds of the State Capitol.

Martha Gruening (1889–1937) was an American-Jewish journalist, poet, suffragette, and civil rights activist, born in Philadelphia. Gruening was an early advocate for the intersectionality of gender, race, and class. Her writings and research for the NAACP led to the advancement of the civil rights movement and worked to include women of color in the fight for women's suffrage.

Brenda Ray Moryck was an American writer associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Lillian Anderson Turner Alexander (1876-1957) was an educator, social worker, civil rights activist, and club woman active in St. Paul, Minnesota and New York City. Before 1918, she was known as Lillian A. Turner with her first husband's surname. After 1918, she used her second husband's surname and was known as Lillian A. Alexander.