Related Research Articles

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around 5 to 20 minutes, although the dreamer may perceive the dream as being much longer than this.

Rapid eye movement sleep is a unique phase of sleep in mammals and birds, characterized by random rapid movement of the eyes, accompanied by low muscle tone throughout the body, and the propensity of the sleeper to dream vividly.

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder or REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a sleep disorder in which people act out their dreams. It involves abnormal behavior during the sleep phase with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The major feature of RBD is loss of muscle atonia during otherwise intact REM sleep. The loss of motor inhibition leads to sleep behaviors ranging from simple limb twitches to more complex integrated movements that can be violent or result in injury to either the individual or their bedmates.

William Charles Dement was an American sleep researcher and founder of the Sleep Research Center at Stanford University. He was a leading authority on sleep, sleep deprivation and the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and narcolepsy. For this pioneering work in a previously uncharted field in the United States, he is sometimes referred to as the American father of sleep medicine.

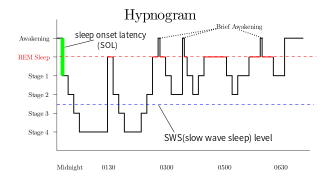

The sleep cycle is an oscillation between the slow-wave and REM (paradoxical) phases of sleep. It is sometimes called the ultradian sleep cycle, sleep–dream cycle, or REM-NREM cycle, to distinguish it from the circadian alternation between sleep and wakefulness. In humans, this cycle takes 70 to 110 minutes. Within the sleep of adults and infants there are cyclic fluctuations between quiet and active sleep. These fluctuations may persist during wakefulness as rest-activity cycles but are less easily discerned.

In the field of psychology, the subfield of oneirology is the scientific study of dreams. Research seeks correlations between dreaming and knowledge about the functions of the brain, as well as an understanding of how the brain works during dreaming as pertains to memory formation and mental disorders. The study of oneirology can be distinguished from dream interpretation in that the aim is to quantitatively study the process of dreams instead of analyzing the meaning behind them.

Reverse learning is a neurobiological theory of dreams. In 1983, in a paper published in the science journal Nature, Crick and Mitchison's reverse learning model likened the process of dreaming to a computer in that it was "off-line" during dreaming or the REM phase of sleep. During this phase, the brain sifts through information gathered throughout the day and throws out all unwanted material. According to the model, we dream in order to forget and this involves a process of 'reverse learning' or 'unlearning'.

Michel Valentin Marcel Jouvet was a French neuroscientist and medical researcher.

Psychoanalytic dream interpretation is a subdivision of dream interpretation as well as a subdivision of psychoanalysis pioneered by Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century. Psychoanalytic dream interpretation is the process of explaining the meaning of the way the unconscious thoughts and emotions are processed in the mind during sleep.

Nathaniel Kleitman was an American physiologist and sleep researcher who served as Professor Emeritus in Physiology at the University of Chicago. He is recognized as the father of modern sleep research, and is the author of the seminal 1939 book Sleep and Wakefulness.

The basic rest–activity cycle (BRAC) is a physiological arousal mechanism in humans proposed by Nathaniel Kleitman, hypothesized to occur during both sleep and wakefulness.

In sleep science, sleep onset latency (SOL) is the length of time that it takes to accomplish the transition from full wakefulness to sleep, normally to the lightest of the non-REM sleep stages.

Ponto-geniculo-occipital waves or PGO waves are distinctive wave forms of propagating activity between three key brain regions: the pons, lateral geniculate nucleus, and occipital lobe; specifically, they are phasic field potentials. These waves can be recorded from any of these three structures during and immediately before REM sleep. The waves begin as electrical pulses from the pons, then move to the lateral geniculate nucleus residing in the thalamus, and end in the primary visual cortex of the occipital lobe. The appearances of these waves are most prominent in the period right before REM sleep, albeit they have been recorded during wakefulness as well. They are theorized to be intricately involved with eye movement of both wake and sleep cycles in many different animals.

Charcot–Wilbrand syndrome (CWS) is dream loss following focal brain damage specifically characterised by visual agnosia and loss of ability to mentally recall or "revisualize" images. The name of this condition dates back to the case study work of Jean-Martin Charcot and Hermann Wilbrand, and was first described by Otto Potzl as "mind blindness with disturbance of optic imagination". MacDonald Critchley, former president of the World Federation of Neurology, more recently summarized CWS as "a patient loses the power to conjure up visual images or memories, and furthermore, ceases to dream during his sleeping hours". This condition is quite rare and affects only a handful of brain damage patients. Further study could help illuminate the neurological pathway for dream formation.

Scholarly interest in the process and functions of dreaming has been present since Sigmund Freud's interpretations in the 1900s. The neurology of dreaming has remained misunderstood until recent distinctions, however. The information available via modern techniques of brain imaging has provided new bases for the study of the dreaming brain. The bounds that such technology has afforded has created an understanding of dreaming that seems ever-changing; even now questions still remain as to the function and content of dreams.

The activation-synthesis hypothesis, proposed by Harvard University psychiatrists John Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley, is a neurobiological theory of dreams first published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in December 1977. The differences in neuronal activity of the brainstem during waking and REM sleep were observed, and the hypothesis proposes that dreams result from brain activation during REM sleep. Since then, the hypothesis has undergone an evolution as technology and experimental equipment has become more precise. Currently, a three-dimensional model called AIM Model, described below, is used to determine the different states of the brain over the course of the day and night. The AIM Model introduces a new hypothesis that primary consciousness is an important building block on which secondary consciousness is constructed.

The neuroscience of sleep is the study of the neuroscientific and physiological basis of the nature of sleep and its functions. Traditionally, sleep has been studied as part of psychology and medicine. The study of sleep from a neuroscience perspective grew to prominence with advances in technology and the proliferation of neuroscience research from the second half of the twentieth century.

Human Givens is the name of a theory in psychotherapy formulated in the United Kingdom, first outlined by Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell in the late 1990s, and amplified in the 2003 book Human Givens: A new approach to emotional health and clear thinking. The human givens organising ideas proffer a description of the nature of human beings, the 'givens' of human genetic heritage and what humans need in order to be happy and healthy based on the research literature. Human Givens therapy draws on several psycho therapeutic models, such as motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy, psychoeducation, interpersonal therapy, imaginal exposure therapy and NLP such as the Rewind Technique, while seeking to use a client's strengths to enable them to get emotional needs met.

Emotions play a key role in overall mental health, and sleep plays a crucial role in maintaining the optimal homeostasis of emotional functioning. Deficient sleep, both in the form of sleep deprivation and restriction, adversely impacts emotion generation, emotion regulation, and emotional expression.

Caetextia is a term and concept first coined by psychologists Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell to describe a chronic disorder that manifests as a context blindness in people on the autism spectrum. It was specifically used to designate the most dominant manifestation of autistic behaviour in higher-functioning individuals. Griffin and Tyrell also suggested that caetextia "is a more accurate and descriptive term for this inability to see how one variable influences another, particularly at the higher end of the spectrum, than the label of 'Asperger's syndrome'".

References

- ↑ Griffin, J and Tyrrell, I (2004) Dreaming Reality: How dreaming keeps us sane, or can drive us mad. Human Givens Publishing, East Sussex. ISBN 1-899398-36-8

- ↑ Aserinsky, E and Kleitman, N (1953). Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science, 18, 273–274.

- ↑ Dement, W and Kleitman, N (1957). Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility and dreaming. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 9, 673–690.

- ↑ Morrison, A R (1983). A window on the sleeping brain. Scientific American, 248, 86–94.

- ↑ Morrison, A R and Reiner, P (1985). A Dissection of Paradoxical Sleep. D J McGinty.

- ↑ Jouvet, M and Michel, F (1959). Corrélations électromyographique du sommeil chez le chat décortiqué et mésencéphalique chronique. Comptes Rendus de la Société de Biologie, 154, 422–425.

- ↑ Jouvet, M (1978). Does a genetic programming of the brain occur during paradoxical sleep? In P A Buser and A Rougel-Buser (eds) Cerebral Correlates of Conscious Experience. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- ↑ Roffwarg, H P, Muzio, J and Dement, W (1966). The ontogenetic development of the human sleep-dream cycle. Science, 152, 604–618.

- ↑ Coble, P A, Kupfer, D J and Shaw, D H (1981). Distribution of REM latency in depression. Biological Psychiatry, 16, 453–466.

- ↑ Berger, M, van Calker, D and Riemann, D (2003). Sleep and manipulations of the sleep–wake rhythm in depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108 (s418), 83–91.

- ↑ Vogel, G W (1979). A motivational function of REM sleep. In Drucker-Colin, R, Shkurovitch, M and Sterman, M B (eds) The function of Sleep. Academic Press, pp 233–50.

- 1 2 Griffin, J and Tyrrell, I (2003, 2nd edition, 2013). Human Givens: a new approach to emotional health and clear thinking. HG Publishing, East Sussex.

- ↑ Freud, S (1953). The Interpretation of Dreams. P 647 of the standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Strackey, J (ed). Hogarth Press.

- ↑ Jung, C (1965). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage Books, pp 158–9.

- ↑ Domhoff, G W (2000). Needed: a new theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 6, 928–30.