Behavior or behaviour is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems or artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or organisms as well as the inanimate physical environment. It is the computed response of the system or organism to various stimuli or inputs, whether internal or external, conscious or subconscious, overt or covert, and voluntary or involuntary.

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definition. Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.

Fear is an intensely unpleasant emotion in response to perceiving or recognizing a danger or threat. Fear causes psychological changes that may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the threat. Fear in human beings may occur in response to a certain stimulus occurring in the present, or in anticipation or expectation of a future threat perceived as a risk to oneself. The fear response arises from the perception of danger leading to confrontation with or escape from/avoiding the threat, which in extreme cases of fear can be a freeze response. The fear response is also implicated in a number of mental disorders, particularly anxiety disorders.

An attitude "is a summary evaluation of an object of thought. An attitude object can be anything a person discriminates or holds in mind." Attitudes include beliefs (cognition), emotional responses (affect) and behavioral tendencies. In the classical definition an attitude is persistent, while in more contemporary conceptualizations, attitudes may vary depending upon situations, context, or moods.

Arousal is the physiological and psychological state of being awoken or of sense organs stimulated to a point of perception. It involves activation of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) in the brain, which mediates wakefulness, the autonomic nervous system, and the endocrine system, leading to increased heart rate and blood pressure and a condition of sensory alertness, desire, mobility, and reactivity.

Behavior change, in context of public health, refers to efforts put in place to change people's personal habits and attitudes, to prevent disease. Behavior change in public health can take place at several levels and is known as social and behavior change (SBC). More and more, efforts focus on prevention of disease to save healthcare care costs. This is particularly important in low and middle income countries, where supply side health interventions have come under increased scrutiny because of the cost.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a psychological theory that links beliefs to behavior. The theory maintains that three core components, namely, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, together shape an individual's behavioral intentions. In turn, a tenet of TPB is that behavioral intention is the most proximal determinant of human social behavior.

Attitudes are associated beliefs and behaviors towards some object. They are not stable, and because of the communication and behavior of other people, are subject to change by social influences, as well as by the individual's motivation to maintain cognitive consistency when cognitive dissonance occurs—when two attitudes or attitude and behavior conflict. Attitudes and attitude objects are functions of affective and cognitive components. It has been suggested that the inter-structural composition of an associative network can be altered by the activation of a single node. Thus, by activating an affective or emotional node, attitude change may be possible, though affective and cognitive components tend to be intertwined.

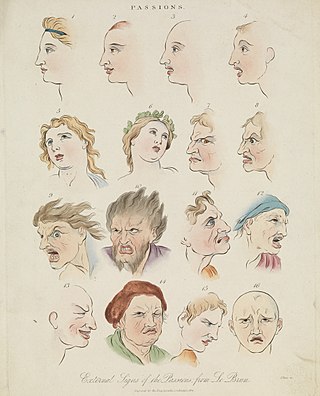

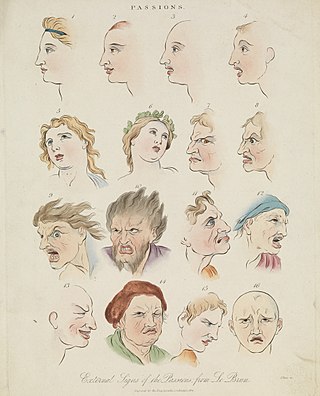

An emotional expression is a behavior that communicates an emotional state or attitude. It can be verbal or nonverbal, and can occur with or without self-awareness. Emotional expressions include facial movements like smiling or scowling, simple behaviors like crying, laughing, or saying "thank you," and more complex behaviors like writing a letter or giving a gift. Individuals have some conscious control of their emotional expressions; however, they need not have conscious awareness of their emotional or affective state in order to express emotion.

In psychology, reactance is an unpleasant motivational reaction to offers, persons, rules, regulations, advice, recommendations, information, and messages that are perceived to threaten or eliminate specific behavioral freedoms. Reactance occurs when an individual feels that an agent is attempting to limit one's choice of response and/or range of alternatives.

Social cognitive theory (SCT), used in psychology, education, and communication, holds that portions of an individual's knowledge acquisition can be directly related to observing others within the context of social interactions, experiences, and outside media influences. This theory was advanced by Albert Bandura as an extension of his social learning theory. The theory states that when people observe a model performing a behavior and the consequences of that behavior, they remember the sequence of events and use this information to guide subsequent behaviors. Observing a model can also prompt the viewer to engage in behavior they already learned. Depending on whether people are rewarded or punished for their behavior and the outcome of the behavior, the observer may choose to replicate behavior modeled. Media provides models for a vast array of people in many different environmental settings.

Behavioural change theories are attempts to explain why human behaviours change. These theories cite environmental, personal, and behavioural characteristics as the major factors in behavioural determination. In recent years, there has been increased interest in the application of these theories in the areas of health, education, criminology, energy and international development with the hope that understanding behavioural change will improve the services offered in these areas. Some scholars have recently introduced a distinction between models of behavior and theories of change. Whereas models of behavior are more diagnostic and geared towards understanding the psychological factors that explain or predict a specific behavior, theories of change are more process-oriented and generally aimed at changing a given behavior. Thus, from this perspective, understanding and changing behavior are two separate but complementary lines of scientific investigation.

Appraisal theory is the theory in psychology that emotions are extracted from our evaluations of events that cause specific reactions in different people. Essentially, our appraisal of a situation causes an emotional, or affective, response that is going to be based on that appraisal. An example of this is going on a first date. If the date is perceived as positive, one might feel happiness, joy, giddiness, excitement, and/or anticipation, because they have appraised this event as one that could have positive long-term effects, i.e. starting a new relationship, engagement, or even marriage. On the other hand, if the date is perceived negatively, then our emotions, as a result, might include dejection, sadness, emptiness, or fear. Reasoning and understanding of one's emotional reaction becomes important for future appraisals as well. The important aspect of the appraisal theory is that it accounts for individual variability in emotional reactions to the same event.

The health belief model (HBM) is a social psychological health behavior change model developed to explain and predict health-related behaviors, particularly in regard to the uptake of health services. The health belief model also refers to an individual's beliefs about preventing diseases, maintaining health, and striving for well-being. The HBM was developed in the 1950s by social psychologists at the U.S. Public Health Service and remains one of the best known and most widely used theories in health behavior research. The HBM suggests that people's beliefs about health problems, perceived benefits of action and barriers to action, and self-efficacy explain engagement in health-promoting behavior. A stimulus, or cue to action, must also be present in order to trigger the health-promoting behavior.

Fear appeal is a term used in psychology, sociology and marketing. It generally describes a strategy for motivating people to take a particular action, endorse a particular policy, or buy a particular product, by arousing fear. A well-known example in television advertising was a commercial employing the musical jingle: "Never pick up a stranger, pick up Prestone anti-freeze." This was accompanied by images of shadowy strangers (hitchhikers) who would presumably do one harm if picked up. The commercial's main appeal was not to the positive features of Prestone anti-freeze, but to the fear of what a "strange" brand might do.

Protection motivation theory (PMT) was originally created to help understand individual human responses to fear appeals. Protection motivation theory proposes that people protect themselves based on two factors: threat appraisal and coping appraisal. Threat appraisal assesses the severity of the situation and examines how serious the situation is, while coping appraisal is how one responds to the situation. Threat appraisal consists of the perceived severity of a threatening event and the perceived probability of the occurrence, or vulnerability. Coping appraisal consists of perceived response efficacy, or an individual's expectation that carrying out the recommended action will remove the threat, and perceived self efficacy, or the belief in one's ability to execute the recommended courses of action successfully.

A behavior change method, or behavior change technique, is a theory-based method for changing one or several determinants of behavior such as a person's attitude or self-efficacy. Such behavior change methods are used in behavior change interventions. Although of course attempts to influence people's attitude and other psychological determinants were much older, especially the definition developed in the late nineties yielded useful insights, in particular four important benefits:

- It developed a generic, abstract vocabulary that facilitated discussion of the active ingredients of an intervention

- It emphasized the distinction between behavior change methods and practical applications of these methods

- It included the concept of 'parameters for effectiveness', important conditions for effectiveness often neglected

- It drew attention to the fact that behavior change methods influence specific determinants.

A health campaign is a type of media campaign which attempts to promote public health by making new health interventions available. The organizers of a health campaign frequently use education along with an opportunity to participate further, such as when a vaccination campaign seeks both to educate the public about a vaccine and provide the vaccine to people who want it. When a health campaign has international relevance it may be called a global health campaign.

Kim Witte is a communications scholar with an emphasis on the area of fear appeals called “scare tactics”. In 2015 Witte is a professor who teaches graduate courses at Michigan State University.

In advertising, a fear pattern is a sequence of fear arousal and fear reduction that is felt by the viewing audience when exposed to an advertisement, which attempts to threaten the audience by presenting a negative physical, psychological or social consequence that is likely to occur if they engage in a particular behaviour. Fear appeals are commonly used in social marketing campaigns. These are sometimes called “threat appeals”, however the label “fear appeals” is justified if the appeal can be shown to arouse fear.