In particle physics, Rutherford scattering is the elastic scattering of charged particles by the Coulomb interaction. It is a physical phenomenon explained by Ernest Rutherford in 1911 that led to the development of the planetary Rutherford model of the atom and eventually the Bohr model. Rutherford scattering was first referred to as Coulomb scattering because it relies only upon the static electric (Coulomb) potential, and the minimum distance between particles is set entirely by this potential. The classical Rutherford scattering process of alpha particles against gold nuclei is an example of "elastic scattering" because neither the alpha particles nor the gold nuclei are internally excited. The Rutherford formula further neglects the recoil kinetic energy of the massive target nucleus.

In particle physics, bremsstrahlung is electromagnetic radiation produced by the deceleration of a charged particle when deflected by another charged particle, typically an electron by an atomic nucleus. The moving particle loses kinetic energy, which is converted into radiation, thus satisfying the law of conservation of energy. The term is also used to refer to the process of producing the radiation. Bremsstrahlung has a continuous spectrum, which becomes more intense and whose peak intensity shifts toward higher frequencies as the change of the energy of the decelerated particles increases.

A composite material is a material which is produced from two or more constituent materials. These constituent materials have notably dissimilar chemical or physical properties and are merged to create a material with properties unlike the individual elements. Within the finished structure, the individual elements remain separate and distinct, distinguishing composites from mixtures and solid solutions.

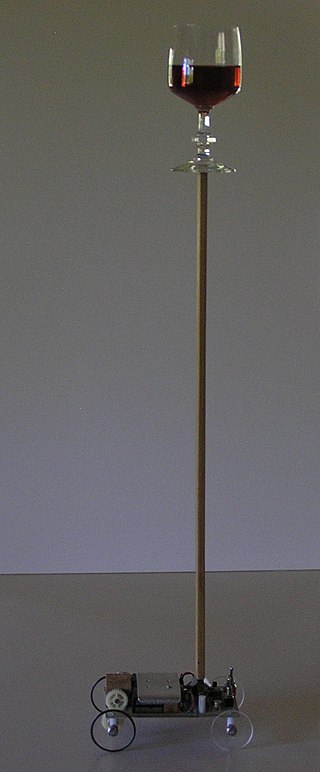

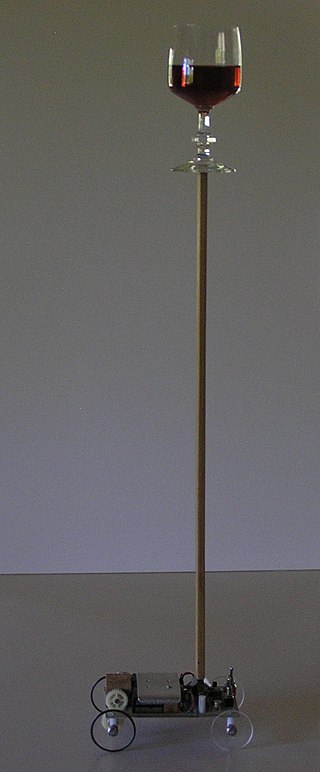

An inverted pendulum is a pendulum that has its center of mass above its pivot point. It is unstable and without additional help will fall over. It can be suspended stably in this inverted position by using a control system to monitor the angle of the pole and move the pivot point horizontally back under the center of mass when it starts to fall over, keeping it balanced. The inverted pendulum is a classic problem in dynamics and control theory and is used as a benchmark for testing control strategies. It is often implemented with the pivot point mounted on a cart that can move horizontally under control of an electronic servo system as shown in the photo; this is called a cart and pole apparatus. Most applications limit the pendulum to 1 degree of freedom by affixing the pole to an axis of rotation. Whereas a normal pendulum is stable when hanging downwards, an inverted pendulum is inherently unstable, and must be actively balanced in order to remain upright; this can be done either by applying a torque at the pivot point, by moving the pivot point horizontally as part of a feedback system, changing the rate of rotation of a mass mounted on the pendulum on an axis parallel to the pivot axis and thereby generating a net torque on the pendulum, or by oscillating the pivot point vertically. A simple demonstration of moving the pivot point in a feedback system is achieved by balancing an upturned broomstick on the end of one's finger.

The Cavendish experiment, performed in 1797–1798 by English scientist Henry Cavendish, was the first experiment to measure the force of gravity between masses in the laboratory and the first to yield accurate values for the gravitational constant. Because of the unit conventions then in use, the gravitational constant does not appear explicitly in Cavendish's work. Instead, the result was originally expressed as the specific gravity of Earth, or equivalently the mass of Earth. His experiment gave the first accurate values for these geophysical constants.

The Kerr metric or Kerr geometry describes the geometry of empty spacetime around a rotating uncharged axially symmetric black hole with a quasispherical event horizon. The Kerr metric is an exact solution of the Einstein field equations of general relativity; these equations are highly non-linear, which makes exact solutions very difficult to find.

A Halbach array is a special arrangement of permanent magnets that augments the magnetic field on one side of the array while cancelling the field to near zero on the other side. This is achieved by having a spatially rotating pattern of magnetisation.

In physics and astronomy, the Reissner–Nordström metric is a static solution to the Einstein–Maxwell field equations, which corresponds to the gravitational field of a charged, non-rotating, spherically symmetric body of mass M. The analogous solution for a charged, rotating body is given by the Kerr–Newman metric.

The Kerr–Newman metric is the most general asymptotically flat and stationary solution of the Einstein–Maxwell equations in general relativity that describes the spacetime geometry in the region surrounding an electrically charged and rotating mass. It generalizes the Kerr metric by taking into account the field energy of an electromagnetic field, in addition to describing rotation. It is one of a large number of various different electrovacuum solutions; that is, it is a solution to the Einstein–Maxwell equations that account for the field energy of an electromagnetic field. Such solutions do not include any electric charges other than that associated with the gravitational field, and are thus termed vacuum solutions.

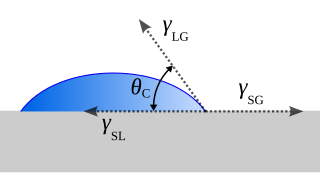

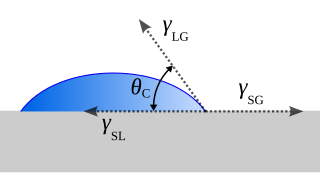

The contact angle is the angle between a liquid surface and a solid surface where they meet. More specifically, it is the angle between the surface tangent on the liquid–vapor interface and the tangent on the solid–liquid interface at their intersection. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation.

In classical mechanics, the shell theorem gives gravitational simplifications that can be applied to objects inside or outside a spherically symmetrical body. This theorem has particular application to astronomy.

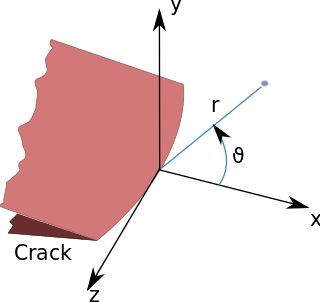

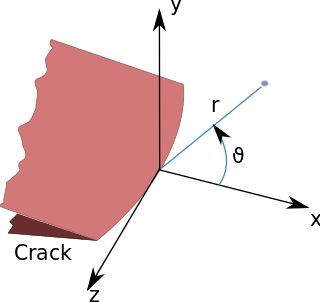

In fracture mechanics, the stress intensity factor is used to predict the stress state near the tip of a crack or notch caused by a remote load or residual stresses. It is a theoretical construct usually applied to a homogeneous, linear elastic material and is useful for providing a failure criterion for brittle materials, and is a critical technique in the discipline of damage tolerance. The concept can also be applied to materials that exhibit small-scale yielding at a crack tip.

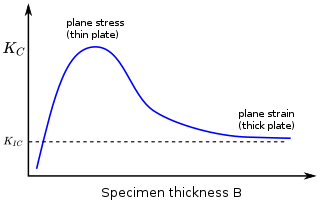

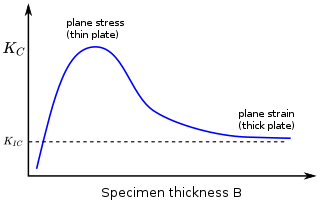

In materials science, fracture toughness is the critical stress intensity factor of a sharp crack where propagation of the crack suddenly becomes rapid and unlimited. A component's thickness affects the constraint conditions at the tip of a crack with thin components having plane stress conditions and thick components having plane strain conditions. Plane strain conditions give the lowest fracture toughness value which is a material property. The critical value of stress intensity factor in mode I loading measured under plane strain conditions is known as the plane strain fracture toughness, denoted . When a test fails to meet the thickness and other test requirements that are in place to ensure plane strain conditions, the fracture toughness value produced is given the designation . Fracture toughness is a quantitative way of expressing a material's resistance to crack propagation and standard values for a given material are generally available.

The J-integral represents a way to calculate the strain energy release rate, or work (energy) per unit fracture surface area, in a material. The theoretical concept of J-integral was developed in 1967 by G. P. Cherepanov and independently in 1968 by James R. Rice, who showed that an energetic contour path integral was independent of the path around a crack.

Ceramic engineering is the science and technology of creating objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials. This is done either by the action of heat, or at lower temperatures using precipitation reactions from high-purity chemical solutions. The term includes the purification of raw materials, the study and production of the chemical compounds concerned, their formation into components and the study of their structure, composition and properties.

A pendulum is a body suspended from a fixed support so that it swings freely back and forth under the influence of gravity. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back towards the equilibrium position. When released, the restoring force acting on the pendulum's mass causes it to oscillate about the equilibrium position, swinging it back and forth. The mathematics of pendulums are in general quite complicated. Simplifying assumptions can be made, which in the case of a simple pendulum allow the equations of motion to be solved analytically for small-angle oscillations.

Rotational diffusion is the rotational movement which acts upon any object such as particles, molecules, atoms when present in a fluid, by random changes in their orientations. Whilst the directions and intensities of these changes are statistically random, they do not arise randomly and are instead the result of interactions between particles. One example occurs in colloids, where relatively large insoluble particles are suspended in a greater amount of fluid. The changes in orientation occur from collisions between the particle and the many molecules forming the fluid surrounding the particle, which each transfer kinetic energy to the particle, and as such can be considered random due to the varied speeds and amounts of fluid molecules incident on each individual particle at any given time.

In materials science, toughening refers to the process of making a material more resistant to the propagation of cracks. When a crack propagates, the associated irreversible work in different materials classes is different. Thus, the most effective toughening mechanisms differ among different materials classes. The crack tip plasticity is important in toughening of metals and long-chain polymers. Ceramics have limited crack tip plasticity and primarily rely on different toughening mechanisms.

Fracture of biological materials may occur in biological tissues making up the musculoskeletal system, commonly called orthopedic tissues: bone, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons. Bone and cartilage, as load-bearing biological materials, are of interest to both a medical and academic setting for their propensity to fracture. For example, a large health concern is in preventing bone fractures in an aging population, especially since fracture risk increases ten fold with aging. Cartilage damage and fracture can contribute to osteoarthritis, a joint disease that results in joint stiffness and reduced range of motion.

Katherine T. Faber is an American materials scientist and one of the world's foremost experts in ceramic engineering, material strengthening, and ultra-high temperature materials. Faber is the Simon Ramo Professor of Materials Science at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). She is also an adjunct professor of Materials Science and Engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science at Northwestern University.