Fabulous Histories (later known as The Story of the Robins) is the best-known work of Sarah Trimmer. Originally published in 1786, it remained in print until the beginning of the twentieth century. [1]

Fabulous Histories (later known as The Story of the Robins) is the best-known work of Sarah Trimmer. Originally published in 1786, it remained in print until the beginning of the twentieth century. [1]

Fabulous Histories tells the story of two families—one of robins and one of humans—who learn to live together congenially. The children and baby robins learn to adopt virtue and to shun vice. For Trimmer, practising kindness to animals as a child would hopefully lead one to "universal benevolence" as an adult. According to Samuel Pickering Jr., a scholar of eighteenth-century children's literature, "in its depiction of eighteenth-century attitudes toward animals, Mrs. Trimmer’s Fabulous Histories was the most representative children’s book of the period." [2]

The text expresses several themes that would dominate Trimmer's later works, such as her emphasis on retaining social hierarchies; as Tess Cosslett, a scholar of children's literature explains: "the notion of hierarchy that underpins Fabulous Histories is relatively stable and fixed. Parents are above children in terms of authority, and humans above animals, in terms both of dominion and compassion: poor people should be fed before hungry animals ... [but] the hierarchical relation of men and women is not so clearly enforced." [3]

Moira Ferguson, a scholar of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, places these themes in a larger historical context, arguing that "the fears of the author and her class about an industrial revolution in ascendancy and its repercussions are evident. Hence, [the] text attacks cruelty to birds and animals while affirming British aggression abroad. ... The text subtly opts for conservative solutions: maintenance of order and established values, resignation and compliance from the poor at home, expatriation for foreigners who do not assimilate easily." [4]

Another overarching theme in the text is rationality; Trimmer expresses the common fear of the power of fiction in her preface, explaining to her childish readers that her fable is not real and that animals cannot really speak. [5] Like many social critics during the eighteenth century, Trimmer was concerned about fiction's potentially damaging impact on young readers. With the rise of the novel and its concomitant private reading, she feared young people and especially women would read racy and adventurous stories without the knowledge of their parents and, perhaps even more worrisome, interpret the books as they pleased. Trimmer therefore always referred to her text as Fabulous Histories and never as The Story of the Robins in order to emphasize its reality; moreover, she did not allow the book to be illustrated within her lifetime—pictures of talking birds would only have reinforced the paradox of the book (it was fiction parading as a history). [6] Yarde speculated that most of the characters in the text are drawn from Trimmer's own acquaintances and family. [7]

Murray Knowles, writing in Language and Control in Children's Literature, states that Trimmer intended the book to be used didactically, [8] a common practice in eighteenth-century children's literature. [9] More than one hundred years later, in Juvenile Literature As It Is, Edward Salmon found "nothing unusually meritorious" about the book, though he noted that it "should be praised for its humane sentiments." [10]

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader, from picture books for the very young to young adult fiction.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1786.

Young adult literature (YA) is typically written for readers aged 12 to 18 and includes most of the themes found in adult fiction, such as friendship, substance abuse, alcoholism, and sexuality. It is characterized by simpler world building than adult literature as it seeks to highlight the experiences of adolescents in a variety of ways. There are various genres within young adult literature.

Jane West (1758–1852), was an English novelist who published as Prudentia Homespun and Mrs. West. She also wrote conduct literature, poetry and educational tracts.

Some Thoughts Concerning Education is a 1693 treatise on the education of gentlemen written by the English philosopher John Locke. For over a century, it was the most important philosophical work on education in England. It was translated into almost all of the major written European languages during the eighteenth century, and nearly every European writer on education after Locke, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, acknowledged its influence.

Sarah Trimmer was an English writer and critic of 18th-century British children's literature, as well as an educational reformer. Her periodical, The Guardian of Education, helped to define the emerging genre by seriously reviewing children's literature for the first time; it also provided the first history of children's literature, establishing a canon of the early landmarks of the genre that scholars still use today. Trimmer's most popular children's book, Fabulous Histories, inspired numerous children's animal stories and remained in print for over a century.

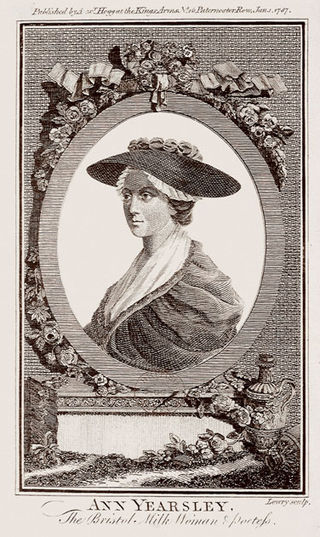

Ann Yearsley, née Cromartie, also known as Lactilla, was an English poet and writer from the labouring class, in Bristol. The poet Robert Southey wrote a biography of her.

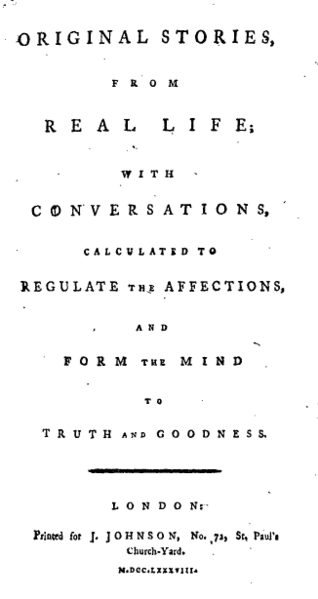

Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness is the only complete work of children's literature by the 18th-century English feminist author Mary Wollstonecraft. Original Stories begins with a frame story that sketches out the education of two young girls by their maternal teacher Mrs. Mason, followed by a series of didactic tales. The book was first published by Joseph Johnson in 1788; a second, illustrated edition, with engravings by William Blake, was released in 1791 and remained in print for around a quarter of a century.

The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes is a children's story published by John Newbery in London in 1765. The story popularized the phrase "goody two-shoes" as a descriptor for an excessively virtuous person or do-gooder. Historian V.M. Braganza refers to it as one of the first works of Children's literature, perhaps the earliest children's novel in English. It was influential to subsequent authors, revolutionary in the development of its literary genre, and popular, noted for its female heroine in a realist setting.

Ellenor Fenn was a prolific 18th-century British writer of children's books.

The academic discipline of women's writing is a discrete area of literary studies which is based on the notion that the experience of women, historically, has been shaped by their sex, and so women writers by definition are a group worthy of separate study: "Their texts emerge from and intervene in conditions usually very different from those which produced most writing by men." It is not a question of the subject matter or political stance of a particular author, but of her sex, i.e. her position as a woman within the literary world.

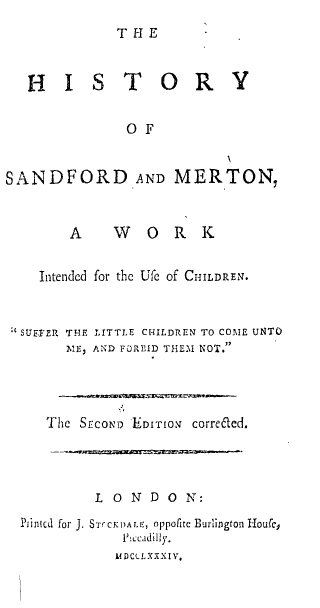

The History of Sandford and Merton (1783–89) was a best-selling children's book written by Thomas Day. He began it as a contribution to Richard Lovell and Honora Sneyd Edgeworth's Harry and Lucy, a collection of short stories for children that Maria Edgeworth continued some years after her stepmother died. He eventually expanded his original short story into the first volume of The History of Sandford and Merton, which was published anonymously in 1783; two further volumes subsequently followed in 1786 and 1789. The book was wildly successful and was reprinted until the end of the nineteenth century. It retained enough popularity or invoked enough nostalgia at the end of the nineteenth century to inspire a satire, The New History of Sandford and Merton, whose preface proudly announces that it will "teach you what to don't".

Lessons for Children is a series of four age-adapted reading primers written by the prominent 18th-century British poet and essayist Anna Laetitia Barbauld. Published in 1778 and 1779, the books initiated a revolution in children's literature in the Anglo-American world. For the first time, the needs of the child reader were seriously considered: the typographically simple texts progress in difficulty as the child learns. In perhaps the first demonstration of experiential pedagogy in Anglo-American children's literature, Barbauld's books use a conversational style, which depicts a mother and her son discussing the natural world. Based on the educational theories of John Locke, Barbauld's books emphasise learning through the senses.

The Guardian of Education was the first successful periodical dedicated to reviewing children's literature in Britain. It was edited by 18th-century educationalist, children's author, and Sunday school advocate Sarah Trimmer and was published from June 1802 until September 1806 by J. Hatchard and F. C. and J. Rivington. The journal offered child-rearing advice and assessments of contemporary educational theories, and Trimmer even proffered her own educational theory after evaluating the major works of the day.

Feminist literature is fiction, nonfiction, drama, or poetry, which supports the feminist goals of defining, establishing, and defending equal civil, political, economic, and social rights for women. It often addresses the roles of women in society particularly as regarding status, privilege, and power – and generally portrays the consequences to women, men, families, communities, and societies as undesirable.

Talking animals are a common element in mythology and folk tales, children's literature, and modern comic books and animated cartoons. Fictional talking animals often are anthropomorphic, possessing human-like qualities. Whether they are realistic animals or fantastical ones, talking animals serve a wide range of uses in literature, from teaching morality to providing social commentary. Realistic talking animals are often found in fables, religious texts, indigenous texts, wilderness coming of age stories, naturalist fiction, animal autobiography, animal satire, and in works featuring pets and domesticated animals. Conversely, fantastical and more anthropomorphic animals are often found in the fairy tale, science fiction, toy story, and fantasy genres.

John Marshall (1756–1824) was a London publisher who specialized in children's literature, chapbooks, educational games and teaching schemes. He called himself the "Children's Printer" and children his "young friends". He was pre-eminent in England as a children's book publisher from about 1780 to 1800. After 1795, he became the publisher of Hannah More's Cheap Repository Tracts, but a dispute with her led to him issuing a similar series of his own. About 1800 Marshall began publishing a series of miniature libraries, games and picture books for children. After his death in July 1824, his business was continued either by his widow or his unmarried daughter, both of whom were named Eleanor.

Elizabeth PinchardnéeSibthorpe, was an English writer of children's fiction whose stories incorporated moral lessons aimed at older girls. She was recognised above all for The Blind Child, her first and most successful novel.