Obiter dictum is a Latin phrase meaning "other things said", that is, a remark in a legal opinion that is "said in passing" by any judge or arbitrator. It is a concept derived from English common law, whereby a judgment comprises only two elements: ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. For the purposes of judicial precedent, ratio decidendi is binding, whereas obiter dicta are persuasive only.

The system of tort law in Australia is broadly similar to that in other common law countries. However, some divergences in approach have occurred as its independent legal system has developed.

A fiduciary is a person who holds a legal or ethical relationship of trust with one or more other parties. Typically, a fiduciary prudently takes care of money or other assets for another person. One party, for example, a corporate trust company or the trust department of a bank, acts in a fiduciary capacity to another party, who, for example, has entrusted funds to the fiduciary for safekeeping or investment. Likewise, financial advisers, financial planners, and asset managers, including managers of pension plans, endowments, and other tax-exempt assets, are considered fiduciaries under applicable statutes and laws. In a fiduciary relationship, one person, in a position of vulnerability, justifiably vests confidence, good faith, reliance, and trust in another whose aid, advice, or protection is sought in some matter. In such a relation, good conscience requires the fiduciary to act at all times for the sole benefit and interest of the one who trusts.

A fiduciary is someone who has undertaken to act for and on behalf of another in a particular matter in circumstances which give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence.

In common law jurisdictions, a misrepresentation is a false or misleading statement of fact made during negotiations by one party to another, the statement then inducing that other party to enter into a contract. The misled party may normally rescind the contract, and sometimes may be awarded damages as well.

Section 51(xx) of the Australian Constitution is a subsection of Section 51 of the Australian Constitution that gives the Commonwealth Parliament the power to legislate with respect to "foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations formed within the limits of the Commonwealth". This power has become known as "the corporations power", the extent of which has been the subject of numerous judicial cases.

Section 51(xxxi) is a subclause of section 51 of the Constitution of Australia. It empowers the Commonwealth to make laws regarding the acquisition of property, but stipulates that such acquisitions must be on just (fair) terms. The terms is sometimes referred to in shorthand as the 'just terms' provision.

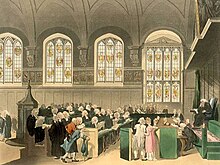

Equitable remedies are judicial remedies developed by courts of equity from about the time of Henry VIII to provide more flexible responses to changing social conditions than was possible in precedent-based common law.

The law of contract in Australia is similar to other Anglo-American common law jurisdictions.

In law, an equitable interest is an "interest held by virtue of an equitable title or claimed on equitable grounds, such as the interest held by a trust beneficiary". The equitable interest is a right in equity that may be protected by an equitable remedy. This concept exists only in systems influenced by the common law tradition, such as New Zealand, England, Canada, Australia, and the United States.

An account of profits is a type of equitable remedy most commonly used in cases of breach of fiduciary duty. It is an action taken against a defendant to recover the profits taken as a result of the breach of duty, in order to prevent unjust enrichment.

Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd , was a decision of the High Court of Australia on 17 April 1985 concerning section 74 of the Constitution of Australia. The Court denied an application by the Attorney-General of Queensland seeking a certificate that would permit the Privy Council to hear an appeal from the High Court's decision in Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd .

Dishonest assistance, or knowing assistance, is a type of third party liability under English trust law. It is usually seen as one of two liabilities established in Barnes v Addy, the other one being knowing receipt. To be liable for dishonest assistance, there must be a breach of trust or fiduciary duty by someone other than the defendant, the defendant must have helped that person in the breach, and the defendant must have a dishonest state of mind. The liability itself is well established, but the mental element of dishonesty is subject to considerable controversy which sprang from the House of Lords case Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley.

Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244 was a decision of the Court of Appeal in Chancery. It established that, in English trusts law, third parties could be liable for a breach of trust in two circumstances, referred to as the two 'limbs' of Barnes v Addy: knowing receipt and knowing assistance.

New South Wales v Commonwealth, commonly known as the Wheat case, or more recently as the Inter-State Commission case, is a landmark Australian judgment of the High Court made in 1915 regarding judicial separation of power. It was also a leading case on the freedom of interstate trade and commerce that is guaranteed by section 92 of the Constitution.

Section 90 of the Constitution of Australia prohibits the States from imposing customs duties and excise duties. The section bars the States from imposing any tax that would be considered to be of a customs or excise nature. While customs duties are easy to determine, the status of excise, as summarised in Ha v New South Wales, is that it consists of "taxes on the production, manufacture, sale or distribution of goods, whether of foreign or domestic origin." This effectively means that States are unable to impose sales taxes.

Muschinski v Dodds, was a significant Australian court case, decided by the High Court of Australia on 6 December 1985. The case was part of a trend of High Court decisions to impose a constructive trust where it would be unconscionable for a legal owner of property to deny the beneficial interests of another. In this case the Court held it would be unconscionable for Mr Dodds to retain a half share of the property without first accounting for the purchase price paid by Ms Muschinski.

Section 122 of the Constitution of Australia deals with matters relating to the governance of Australian territories. It gives the Commonwealth Parliament complete legislative power over the territories. This power is called the territories power. The extent and terms of the representation of the territories in the House of Representatives and the Senate are also stated as being at the discretion of the Commonwealth Parliament.

Bunny Industries v FSW Enterprises is a decision of the Supreme Court of Queensland.

Briginshaw v Briginshaw (Briginshaw) is a decision of the High Court of Australia which considered how the requisite standard of proof should operate in civil proceedings.

Port of Melbourne Authority v Anshun Pty Ltd is a decision of the High Court of Australia.