Related Research Articles

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders, after which the stock exchange decreases the price of the stock by the dividend to remove volatility. The market has no control over the stock price on open on the ex-dividend date, though more often than not it may open higher. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-invested in the business. The current year profit as well as the retained earnings of previous years are available for distribution; a corporation is usually prohibited from paying a dividend out of its capital. Distribution to shareholders may be in cash or, if the corporation has a dividend reinvestment plan, the amount can be paid by the issue of further shares or by share repurchase. In some cases, the distribution may be of assets.

A dividend tax is a tax imposed by a jurisdiction on dividends paid by a corporation to its shareholders (stockholders). The primary tax liability is that of the shareholder, though a tax obligation may also be imposed on the corporation in the form of a withholding tax. In some cases the withholding tax may be the extent of the tax liability in relation to the dividend. A dividend tax is in addition to any tax imposed directly on the corporation on its profits. Some jurisdictions do not tax dividends.

Capital gain is an economic concept defined as the profit earned on the sale of an asset which has increased in value over the holding period. An asset may include tangible property, a car, a business, or intangible property such as shares.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is an Australian statutory agency and the principal revenue collection body for the Australian Government. The ATO has responsibility for administering the Australian federal taxation system, superannuation legislation, and other associated matters. Responsibility for the operations of the ATO are within the portfolio of the Treasurer of Australia and the Treasury.

A corporate tax, also called corporation tax or company tax, is a type of direct tax levied on the income or capital of corporations and other similar legal entities. The tax is usually imposed at the national level, but it may also be imposed at state or local levels in some countries. Corporate taxes may be referred to as income tax or capital tax, depending on the nature of the tax.

Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920), was a tax case before the United States Supreme Court that is notable for the following holdings:

An income trust is an investment that may hold equities, debt instruments, royalty interests or real properties. It is especially useful for financial requirements of institutional investors such as pension funds, and for investors such as retired individuals seeking yield. The main attraction of income trusts, in addition to certain tax preferences for some investors, is their stated goal of paying out consistent cash flows for investors, which is especially attractive when cash yields on bonds are low. Many investors are attracted by the fact that income trusts are not allowed to make forays into unrelated businesses; if a trust is in the oil and gas business, it cannot buy casinos or motion picture studios.

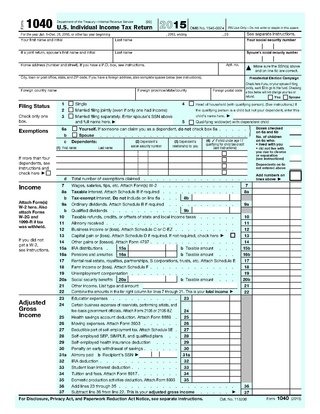

The United States federal government and most state governments impose an income tax. They are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allowable deductions. Income is broadly defined. Individuals and corporations are directly taxable, and estates and trusts may be taxable on undistributed income. Partnerships are not taxed, but their partners are taxed on their shares of partnership income. Residents and citizens are taxed on worldwide income, while nonresidents are taxed only on income within the jurisdiction. Several types of credits reduce tax, and some types of credits may exceed tax before credits. Most business expenses are deductible. Individuals may deduct certain personal expenses, including home mortgage interest, state taxes, contributions to charity, and some other items. Some deductions are subject to limits, and an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) applies at the federal and some state levels.

Income tax in Australia is imposed by the federal government on the taxable income of individuals and corporations. State governments have not imposed income taxes since World War II. On individuals, income tax is levied at progressive rates, and at one of two rates for corporations. The income of partnerships and trusts is not taxed directly, but is taxed on its distribution to the partners or beneficiaries. Income tax is the most important source of revenue for government within the Australian taxation system. Income tax is collected on behalf of the federal government by the Australian Taxation Office.

The Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia. It is one of the main statutes under which income tax is calculated. The Act is gradually being rewritten into the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, and new matters are generally now added to the 1997 Act.

Bottom of the harbour tax avoidance was a form of tax avoidance used in Australia in the 1970s. Legislation made it a criminal offence in 1980. The practice came to symbolise the worst of variously contrived tax strategies from those times.

Cridland v Federal Commissioner of Taxation, was a 1977 High Court of Australia case concerning a novel tax scheme whereby some 5,000 university students became primary producers for tax purposes, allowing them certain income averaging benefits. The Australian Taxation Office held this was tax avoidance, but the test case was decided in favour of the taxpayer, one of the students, Brian Cridland.

Income taxes in Canada constitute the majority of the annual revenues of the Government of Canada, and of the governments of the Provinces of Canada. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2018, the federal government collected just over three times more revenue from personal income taxes than it did from corporate income taxes.

Cherry picking tax avoidance was a form of tax avoidance used in Australia in the 1970s and early 1980s. Company contributions to a superannuation fund were claimed as tax deductions, but the money immediately went back to the company.

Mullens v Federal Commissioner of Taxation, was a 1976 High Court of Australia tax case concerning arrangements where stockbrokers Mullens & Co accessed tax deductions for monies subscribed to a petroleum exploration company. The Australian Taxation Office held the scheme was tax avoidance, but the court found for the taxpayer.

Income taxes are the most significant form of taxation in Australia, and collected by the federal government through the Australian Taxation Office. Australian GST revenue is collected by the Federal government, and then paid to the states under a distribution formula determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission.

Slutzkin v Federal Commissioner of Taxation, was a High Court of Australia case concerning the tax position of company owners who sold to a dividend stripping operation. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) claimed the proceeds should be treated as dividends, but the Court held they were a capital sum like an ordinary investment asset sale.

Corporate tax is imposed in the United States at the federal, most state, and some local levels on the income of entities treated for tax purposes as corporations. Since January 1, 2018, the nominal federal corporate tax rate in the United States of America is a flat 21% following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. State and local taxes and rules vary by jurisdiction, though many are based on federal concepts and definitions. Taxable income may differ from book income both as to timing of income and tax deductions and as to what is taxable. The corporate Alternative Minimum Tax was also eliminated by the 2017 reform, but some states have alternative taxes. Like individuals, corporations must file tax returns every year. They must make quarterly estimated tax payments. Groups of corporations controlled by the same owners may file a consolidated return.

The Australian dividend imputation system is a corporate tax system in which some or all of the tax paid by a company may be attributed, or imputed, to the shareholders by way of a tax credit to reduce the income tax payable on a distribution. In comparison to the classical system, dividend imputation reduces or eliminates the tax disadvantages of distributing dividends to shareholders by only requiring them to pay the difference between the corporate rate and their marginal rate. If the individual’s average tax rate is lower than the corporate rate, the individual receives a tax refund.

Corporate taxes in Canada are regulated at the federal level by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). As of January 1, 2019 the "net tax rate after the general tax reduction" is fifteen per cent. The net tax rate for Canadian-controlled private corporations that claim the small business deduction, is nine per cent.

References

- The Odyssey Continues: Part IVA post Peabody , Michael D'Ascenzo, Second Commissioner of Taxation, 13 June 2003

- Mary Genevieve Peabody and Commissioner of Taxation [ permanent dead link ], Federal Court report G116 of 1990, at AustLII, in favour of the Commissioner.

- Mary Genevieve Peabody and Commissioner of Taxation [ permanent dead link ], Federal Court report No. Q G146 of 1992, at AustLII, in favour of Peabody.

- Commissioner of Taxation v Peabody (1994) High Court report, at AustLII, in favour of Peabody.